For 14 years now, there has been a hardware store on Francisco Guerra Street in Badajoz identified by a blue awning. The business has a customer rating of 4.5 out of 5 on Google. Its sign advertises "sharpening, key copies, and repairs." It also gives it a name: Makgyver. "We liked the series, and the idea came to my partner," says Jose Salcedo over the phone. The owners changed the 'c' to a 'k' and registered the name of their brand. This way, they avoided copyright issues without altering its pronunciation.

In this place in Extremadura, homage is paid to MacGyver, the 80s TV hero identified as the lay saint of handymen and fans of Bricomanía. Do you remember the saying "You're more dangerous than MacGyver in a hardware store"? Well, that is the best advertising campaign for this store in Badajoz.

Forty years after its premiere in the United States, it is pertinent to analyze the cultural and social impact of a series that no television critic would include in a ranking of the best fictions in the history of the medium. That doesn't matter. MacGyver's strength lies in its challenge to orthodoxy. Neither the protagonist nor his context, not even his marketing strategy, seemed destined to succeed on television. What happened was so surprising that even a character without much substance has become a literary eponym for a couple of generations. Like a quixote, a don juan, or a celestina, talking about a MacGyver has its own recognizable meaning (take note, illustrious members of the RAE) that is identified with someone capable of fixing something with whatever is at hand.

As the hardware store in Badajoz shows us, MacGyver is a sentimental memory of Spain.

It doesn't matter that it hasn't aged well as a television product. A rewatch of any of its 139 episodes, if you set aside nostalgia, is tough. Cardboard sets galore. Remember the episode set in the Basque Country where there were locals with berets looking like extras from The Godfather who had kidnapped a geologist to build an atomic bomb. It was as glorious for the national television esteem of the 80s as the appearance of muse Ana Obregón in The A-Team.

"The plots of each MacGyver episode don't last more than five minutes, which is fascinating," comments Javier Matesanz over the phone, author of One More in the 80s Family. I love it when a plan comes together (Ed. Dolmen), a book dedicated to the series of this decade. "No one remembers a plot, but they do remember that the character was able to escape from Fort Knox with a pack of cigarettes."

Why in the summer of 1984, all the blockbusters were in the cinema: "If Reagan hadn't existed, Spielberg would have invented him"

The secret history of the Ghostbusters: from an overdose to a movie star who barked like a dog

Its lightness is what hooks us. MacGyver is not a work of art, it's a pop happiness boost. Which is much more than what most series in the current streaming overdose offer. Especially in a society like ours, so obsessed with nostalgia. In which cultural concepts like forevism, coined by the thinker Grafton Tanner, are very fashionable and seek to explain how the crisis of imagination in art regarding the future leads to an exaltation of all past times. MacGyver is proof of this.

"MacGyver will not go down in history for its artistic quality, but something that stays in sentimental memory for so long undoubtedly has something," Matesanz continues. "It faithfully represents what the series of the 80s were like. An idealistic and simplistic structure, as well as weak premises and characters that were only sketched with a couple of strokes. Where there was violence but no one ever died." And he adds: "But it worked."

That special something is due to the main character. Perhaps because from its inception, it was shown as a rarity, a counterintuitive impact for the viewer. So much so that the creators of the project saw it destined to end up in the graveyard of serious TV series run by networks and production companies.

The original script of the first MacGyver is the work of Lee David Zlotoff, a writer from the iconic Hill Street Blues. Someone with the courage to create a character with a premise as crazy as groundbreaking: a hero who is against firearms. To justify this conviction that Zlotoff defended in real life, he narrated a childhood trauma of the character in which a friend of his had died from a gunshot. If MacGyver's pacifism in a time when in the United States the Rifle Association had more followers than the Red Cross was already revolutionary, it was even more so to create the first nerd heartthrob in history.

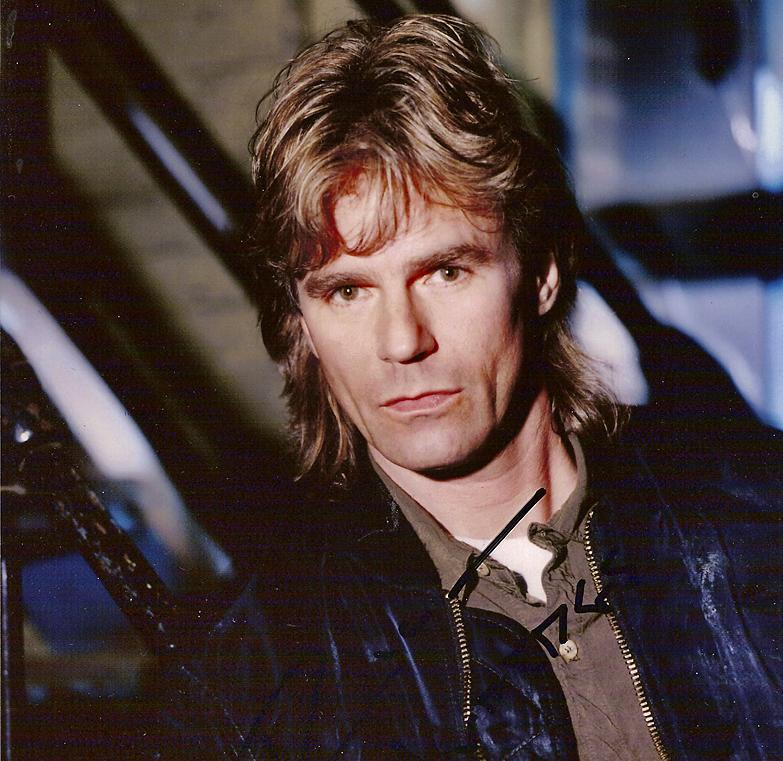

Richard Dean Anderson was chosen to play him, an actor seasoned in the American soap opera industry. This very successful choice had a lot of intuition. When producer Henry Winkler read the pilot script, he liked that this actor took out reading glasses from his pocket to read his lines. "It was a symbol of humility ideal for the role of a discreet genius," Winkler commented in an interview at the time. So, early presbyopia was what turned Anderson into a star.

The series would also have another stroke of luck and talent: its soundtrack. "The story began a long time ago, in a distant land... when the pilot episode was filmed, which was done hastily because in those times, it was considered unlikely for a first episode to become a full series on such a competitive network, with brutal pressure from seasonal bets...," explains Randy Edelman, musician and author of the (legendary) soundtrack of MacGyver and many others from late-century Hollywood, at 80 years old via email. Surely you remember: TA-TATATA-TÁ-TATATÁ...

Edelman, who composed the score in record time, had a hard time getting it accepted: "To write it, they only gave me a vague concept about a guy who could make a bomb with a chocolate bar...," he admits.

To understand how difficult it was for a mainstream network to bet on MacGyver in 1985, you have to know that the heroes of that time - see in the movies those represented by Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger and on TV The A-Team and David Hasselhoff with chest hair and a black leather jacket from Knight Rider - were something like a testosterone earthquake. So, it was strange that in prime time, Angus MacGyver, a geek who used his brain as a sword and science as a shield, appeared. If he was also an honest and friendly guy who sported a mullet hairstyle (short on top and shoulder-length at the back) without blushing, everything was fantastic.

The truth is that in the first weeks of airing, MacGyver was in danger of cancellation until a curious time slot change worked the miracle. It went from night to afternoon. Suddenly, from one week to the next, all of the US adored the character played by Richard Dean Anderson, which was soon exported to different countries, including Spain, where it premiered in 1987 on Televisión Española.

Do you remember who MacGyver was? We're talking about a secret agent who worked for the Phoenix Foundation, which no one really knew what it was or who ran it. At first, the villains he fought were Russian, but soon evil became globalized in the MacGyver universe, which saw the end of the Cold War. To defeat them, the hero improvised solutions using everyday items ranging from chewing gum to a fire extinguisher. This man was capable of disarming a missile with a paper clip, using a log as a hydraulic jack, and stopping a sulfuric acid leak with chocolate. Armed, of course, with his Swiss Army knife, the best branded content product in the history of television.

All his experiments created a legion of fans. Just take a look at YouTube to see recreations of his tricks. The imagination of his writers was fabulous.

In one mission, our hero is in Central America to rescue a downed pilot. In the middle of the job, his jeep breaks down because of a leak in the radiator. No problem. MacGyver finds a chicken, takes some eggs, and repairs the radiator with the egg whites. In another episode, his friend Angus is locked in a cold storage room. No need to worry. Using a metal bar as a channel, he melts part of the ice with the light bulb acting as a heat source. The melted water is channeled into the lock, then refreezes, and the hero opens the door effortlessly.

These examples are child's play compared to his escape from the Alps, when MacGyver is pursued by Soviet soldiers who enlist the help of a psychic [ah, how wonderful those lysergic scripts are] to search for a downed plane in East Germany. How does one escape from mountains over 4,000 meters high? Well, MacGyver does it with a hot air balloon he builds out of gas cylinders, nylon, and the roof of a shed.

Fans of these outrageous inventions coined the term "MacGyverisms" to describe real-life situations in which they used common household items to solve complicated problems. MacGyverisms were described in thousands of letters sent by fans from all over the world to the American network that broadcast the series. In one of them, a viewer admitted to using a pen and a shoelace to repair a broken carburetor. We're not just talking about ordinary people. Emergency services workers and military personnel also reported using MacGyver-inspired techniques to solve problems. One can be sure that sooner or later MacGyverisms will have great anthropological value.

Such was his popularity that Anderson—who earned $775,000 per episode—took the recreation of his character's tricks so seriously that he asked the series' scientific advisors to explain the physical or chemical processes behind what he was going to portray.

MacGyver, que dejó de producirse en 1992 por el agotamiento de Anderson, es el mito escapista de Paty y Selma, las hermanas de Marge en Los Simpson, recurso muy rentable de los vendedores de camisetas nostálgicas en internet y hasta título de un sesudo ensayo llamado MacGyver: La Psicología de la Improvisación y la Filosofía de la Resolución Creativa.

Por ser es hasta un libro de citas de políticos. Su mayor valedor: Pablo Iglesias. Quien para acusar de poca coherencia ideológica a algún rival político ha usado en varias ocasiones la muletilla: «Este es como el chicle de MacGyver, sirve para pegar todo». Ya saben, macgyverismos nostálgicos.