We are in the summer of 1980, and the newborn Spanish democracy is trying to take its first steps. Just a few weeks ago, Felipe González's PSOE tried to overthrow Adolfo Suárez's government with a vote of no confidence that the president managed to survive. The effects of the second oil crisis are being felt in the pockets of many Spanish households. Jordi Pujol has just become the first President of the Generalitat de Cataluña to the astonishment of Catalan socialism. On television, radio, and newspapers, the murder of the Marquises of Urquijo provides its dose of crime news. The images of their bodies riddled in bed and the interior of their luxurious villa in Somosaguas are on every imaginable cover.

In that political-social mix, the first cultural scenes born in democracy begin to emerge. The concept of urban tribes settles in our country. The hedonistic message of the Madrid Movida begins to make itself felt in the capital's nights. Pedro Almodóvar amplifies the phenomenon with the nocturnal revelries of Carmen Maura, Alaska, and Eva Siva in Pepi, Luci, Bom, and other average girls - who could escape that scene of the golden shower in a country that just five years earlier barely tolerated a woman's chest pointing from the screen to the viewers. In Barcelona, a punk and hardcore scene grows, shouting its disdain for its newly elected president. From the United States and Great Britain, as a seasoning, come the sounds of rock, punk, new wave... And one man is determined that the Spaniards can listen to them. And not through a record player or a radio cassette player. In the most rigorous live performance.

The new rules of Spanish pop: "Before they would say: 'These are your 12 songs, record them'"

Carla Simón and Xulia Alonso, the story of two generations wounded by heroin and AIDS

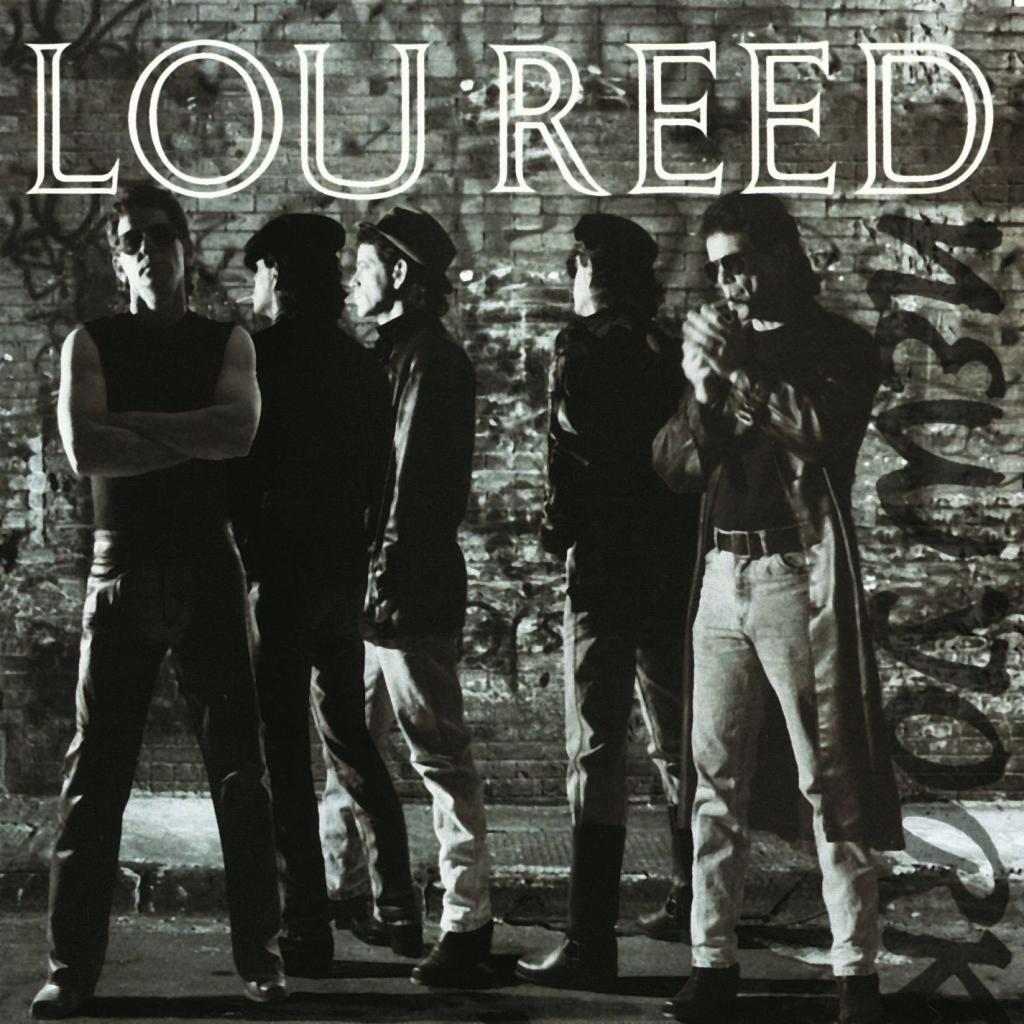

"Damn, I don't know how much I'll remember from those years, which were very tough," comments Gay Mercader on the phone from a Catalan farmhouse where he now lives retired. He had been the one who brought the Rolling Stones to Barcelona in 1976 - almost as an inauguration of the new times after Franco's death - to celebrate the first massive rock concert in Spain. And the summer of 1980 was going to be the grand finale: Lou Reed, the great cursed star of the moment, was going to play at the Moscardó Stadium in Madrid; Bob Marley, the undisputed king of reggae, was supposed to perform in the capital and in Barcelona, and The Ramones were going to debut in our country at the PSUC party in the Catalan city.

Three international stars to inaugurate those new times. Three international stars to set a country on fire. Almost literally. Because the three concerts ended up becoming memorable events for many of those present, but also a series of pitched battles, destroyed cars, stage invasions... And this is nothing but the memory, more or less fuzzy, according to those involved.

Circulation in Madrid was in chaos - now it wouldn't surprise anyone - due to a truckers' strike. In the Usera neighborhood, thousands of people, with a few beers and no less substances in their bodies, awaited Lou Reed's presence at the doors of the Román Valero Stadium, known to all as the Moscardó Stadium. The Brooklyn singer had arrived just before the scheduled start time, but the sound team was still lost wandering around the Legazpi area, on the other side of the Manzanares River. Minutes pass, an hour passes, and people continue to wait for someone to appear on stage. But almost two hours past the set time, nothing. First anger and the show hadn't even started.

"Lou Reed was a son of a bitch, a bitter man. Because having talent doesn't mean you're not a son of a bitch. I never even got to greet him, and I organized all his concerts here. The bastard looked for anything he could find to mess things up, and that day he was angry because nothing was going as he expected," recounts Gay Mercader, present near the dressing room when the singer finally decides to take the stage to play his songs. That was the year of Growing Up in Public, but, according to the chronicles of the time, at the start of the concert, Sweet Jane, I'm Waiting for the Man, Vicious, Walk on the Wild Side... Many of his mythical songs were played. Until an object - still unidentified 45 years later - flew towards the stage. The legend - which in this case is almost gospel - says that the object was a coin, a lighter, a can... and then Lou Reed disappears from the stage. "He was very angry, he said he wouldn't go back up there. What I was told is that later on the bus, he started fighting with those who had hired his European tour for bringing him here," emphasizes the concert promoter.

After that, Lou Reed never came back out, and the sound technicians started dismantling the stage. With tempers already hot due to the concert's delayed start, the Moscardó turned into a battlefield: spectators began to invade the stage, destroy everything on it, take what they could, engage in fights among themselves... The police officers were unable to contain that irate crowd and ended up giving up. Because even before the show started, they had trouble controlling the singer's fans who were trying to sneak into the venue without a ticket. "That is one of the scariest days I've had in my career. Seriously, the police should have intervened for real. I was there next to the stage, and all I could hear was light bulbs shattering on the ground, I saw people carrying spotlights, instruments, microphone stands... They took everything, it was a robbery like those seen in movies," details Mercader.

The chaos inside the stadium also spilled over into the streets of the Usera neighborhood. Spectators carrying all kinds of material, cars with shattered windows from the blows, trash cans and benches torn out, crowds of people in the streets and fights on every corner. Hours later, the police intercept a Lou Reed fan with his drum kit in Plaza de Castilla, on the other side of the city. The promoter decided to sue the singer for breach of contract, but the lawsuit did not succeed. The losses, according to the press, ranged from five to ten million pesetas. "I lost a fortune, I won't tell you how much because I don't remember exactly, but a fortune. Also, insurance companies are there not to pay you anything," explains Gay Mercader, who decided not to refund the ticket money to those who had attended. "People have never wanted to pay for music; they think it's free to put on a concert like that, and I had nothing to give them back for that," the promoter replies over the phone.

Beyond the now almost epic story dubbed The Fly Mutiny that followed Lou Reed's concert in Madrid, the artist's departure and the events that followed had their consequences. Gay Mercader had scheduled the first of two concerts Bob Marley was to give in Spain for a few days later at the same stadium. The civil governor of Madrid, Juan José Rosón, who had also just been appointed Minister of the Interior by Adolfo Suárez, decided that the concert would not take place. "Rosón said he was a subversive artist. A subversive Bob Marley! And that putting on that concert posed a danger to the citizens. But what a danger, damn it! I still had to pay for it even if we didn't do it," explains the promoter, who refuses to give the exact figure of how much money he had to pay at the time. "Just as I don't ask you what you're paid for your work, I'm not going to tell you what I paid for that concert," he adds. [Even telling him the salary doesn't reflect what he paid.]

And so we arrive at the second important date of that summer in the early 1980s.

June 30, 1980

The Peninsula had never seen Bob Marley up close—only a previous performance in Ibiza in 1978—and it would never see him again. Eleven months after landing in Barcelona, he would die of cancer, which the singer refused to treat for three years. This was going to be the only chance to enjoy the great reggae legend in our country after the Madrid date fell through. And the chosen venue was the Monumental, the bullring that still stands in the heart of L'Eixample, with 18,000 tickets sold. Bob Marley, in a bullring. "There were no secrets here; with Marley and his team, it was super easy to negotiate because they were great guys," says Gay Mercader.

The few photos that survive from that night—one of which graces the cover of this supplement—were taken by Francesc Fàbregas, who was working for the music magazine Vibraciones at the time. "I was really busy at that time, it's hard to remember many things. But Marley was hypnotic. And I say this without being high, although I may have been a little because of what the people around me were smoking. Just seeing him, his posture, his way of acting, was hypnotizing. He was like a contemporary dancer," notes the photographer, who had already photographed him in Ibiza.

But problems were yet to appear before the concert, and they had to be linked, of course, to its cancellation in Madrid. Many of those who hadn't been able to get tickets for the concert in the capital decided to travel from other cities across Spain to Barcelona with the intention of seeing Bob Marley in the bullring. Although the capacity was expected to be 18,000, according to articles from the time, there were many more people. Even the stands behind the stage were packed. At the doors, the police were trying to contain the audience, who continued to try to sneak in or enter legitimately with their tickets, even though the opening act, Average White Band, had already started.

"Marley was hypnotic. And I say this without being stoned, although I may have been a little because of what the people around me were smoking."

Again, referring to the press of the time, they describe riots, overturned cars in the vicinity of the venue, and heavy police action. In fact, given the excessive number of people who had managed to enter the bullring, the officers were forced to close the doors, leaving out some who had bought tickets for the Barcelona concert. "I don't remember anything about it, but it was a tremendous concert. I spent half the show on stage with Marley's equipment. They had a drum kit that looked like a toy, which they could have sold at El Corte Inglés." "But you could give those guys a shoebox and they'd make it sound just as good," says Gay Mercader.

All the anthems the Jamaican had composed in his career were played that night in Barcelona. According to various sources, Marley played "No Woman, No Cry," "Jammin'," "Is This Love," "I Shot the Sheriff," "Get Up," "Stand Up," and a "Redemption Song," which is remembered for the fact that the entire venue fell silent to listen to him alone, without the band or his backup singers, playing the guitar to the rhythm of that song. This was recounted in the Arts and Letters supplement of the Heraldo de Aragón, by modern music expert Juan José Blasco Panamá. But there was still one event that would add to the legend of the last time the Jamaican set foot on Spanish soil.

The previous year, in 1979, the Lois jeans brand had popularized a Spanish television advertisement that said, "If your Lois moves, let it dance," while showing the butts of several boys and girls on a beach, squeezing into the company's jeans. The reggae beat that accompanied them behind was that of Three Little Birds. And Marley wasn't going to miss the opportunity to play it in front of a Spanish audience, reportedly the only time he performed it live with The Wailers, his band. "Since there were so few Marleys, there was never a bad face for anything, and the level of quality on stage was assured," notes Gay Mercader.

Within Barcelona, or Gay Mercader's promotion company, the third date would be the closing act of the summer. And in an unexpected setting.

September 19, 1980

The Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC) held the third edition of its Festa del Treball (Work Festival). The big day for the Catalan communists that year would feature the rockabilly of Los Rebeldes, the classic rock of Los Rapidos—the first group formed by Manolo García, later leader of El último de la fila—the folk of Mike Olfield, the flamenco guitar of Diego Cortés, and, of course, the punk of Los Ramones in their first Spanish experience. On the Montjuïc esplanade, in front of the fountain that Carles Buïgas had built for the 1929 Expo, the four members of the band were set to make an appearance, fronted by the immense Joey, at the height of the new wave boom.

"I remember the PSUC (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party) asked us to throw them a big party, and we made them a hell of a mix. Mike Olfield, Diego Cortés, and The Ramones. You think about it now, and it's fucking crazy. But they'd never had so many people there," says Gay Mercader, who doesn't remember if admission was free, but does remember that there were "an awful lot" of people. "There could have been around 100,000, but I'm not sure," the promoter adds. Chronicles from the time go even further, estimating the capacity at 150,000. It was precisely this wild crowd that the Spanish television program Musical Express blamed the fact that the sound wasn't "as pleasant, melodious, and decent" as it should have been. "That would be what Primavera Sound is today; the Catalan communists put on the first major festivals seen here. Imagine how things have changed," notes Francesc Fàbregas, who was also a photographer at that open-air concert.

What the punk fans who came to the Catalan communists' party were looking for wasn't the crisp sound of The Ramones. It was jumping, yelling... and, why not, causing trouble. After Lou Reed and Bob Marley, the closing of that musical summer couldn't have been any less. The crowd watching The Ramones was so large that the audience ended up breaking through the security cordon, smashing through the protective barriers unopposed by the officers, climbing onto the stage, and causing a power outage that left the entire venue in darkness. "Before they jumped over the barriers, the staff was very depressed, but when they jumped over them, they really enjoyed themselves. We have to be less restrictive," Joey himself declared into a TVE microphone just after the concert. "That was quite an event; I remember that esplanade packed with people. What I don't remember is if everything was free, if there was an inner area for those who had paid... there were just people, people, and more people," explains Fàbregas, who still retains his first impression of the group. "They were very impressive: a two-meter-tall singer, a guy with a bass that reached the floor..."

That huge crowd, however, may not have existed. A legend goes—and it doesn't matter much if it's true—that Johnny Ramone didn't know where they were going to play in Spain, that he didn't even know they were going to participate in a Spanish communist party festival. But the rest of the band members had agreed not to tell him anything because of the hatred he felt toward that ideology. Shortly before the show began, Joey decided to tell it as a joke, so everyone would laugh before they stepped onto the Montjuïc stage. The anger was so great that the concert was almost canceled.

And so that summer could have been different.