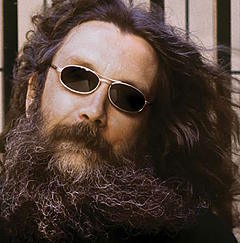

First paradox: the person who has done the most to demystify superpowers looks like he possesses them. Starting with green eyes that seem like they could shoot laser beams. Then, a face entrenched between a long ashy beard and an equally bushy matching mane that gives him a Zeus-like air. And finally, hands covered in rings, ready to cast spells from his fingertips. The image of the wizard is not random, as Alan Moore (Northampton, 1953) is indeed a magician and an expert in the occult arts, much like Aleister Crowley.

Second paradox - many more will come - the acclaimed best comic book writer in the world wants nothing to do with the art in which he achieved what no one else has. He made one of his characters, the revolutionary anti-fascist V, transcend the pages of 'V for Vendetta' (1982-1989), with his Guy Fawkes mask becoming a symbol of resistance for movements worldwide. Moreover, he dissected the superhero concept in 'Watchmen' (1986-1987), an obituary of the extraordinary man created in 1938 by two post-adolescent Jewish boys from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who named him Superman. Above all, he is credited with injecting anarchism into a medium persecuted and later co-opted by conservative forces, such as comics.

Yet, Moore does not want his words to appear in a speech bubble within a panel.

"Forty years ago, most of my interviewers asked me about the wonderful possibilities I saw for comics in the future," recalls the British author in a lengthy email. That faith in the future of the format has now been replaced by nostalgia for the past. In other words, for the comics of that time. "Was it really 40 years ago the last time it seemed like comics had a future?" he leaves hanging.

In any case, for him, they no longer do. His last series, 'Providence,' is from seven years ago. His native Northampton, where he lives with his wife, Melinda Gebbie, has been the inspiration for his first two novels, 'Voice of the Fire' (1996) and 'Jerusalem' (2016), halfway between - another contradiction - the narrative of historical events and the supernatural.

Now Moore has embarked on an ambitious narrative project, which he has called 'Eternal London,' and its first novel (of five planned) is 'The Big When,' just published in Spain by Nocturna Ediciones. In 1949, when the rubble of World War II still occupies both banks of the Thames, a young bookseller discovers a hidden London that has a touch of an LSD trip, surrealistic painting, and once again, spatiotemporal paradox. Just as 'From Hell' (1989-1996), his comic about Jack the Ripper, proposed an investigation of the stories encoded in the architecture of the English capital, this third novel is an invitation to the act of imagining through psychogeography. "Although both are set in London and have some superficial similarities - both, to varying degrees, combine fiction and established history - they are very different works," clarifies the author. 'The Big When' is, according to him, "an extravagant fantasy that may be best described as a highly elastic 'skin' of the imaginary stretched over an obstinately immovable armor of historical lives and circumstances."

Moore has the theory that science, politics, or any other facet of human knowledge are nothing but some of the dismembered remains of Paleolithic magic. "'The hidden, or occult, shows us precisely what the visible or illuminated has overlooked, because it was invisible, unilluminated," he says in defense of the esoteric. "And the unilluminated field of what we do not know is an immense, unlimited darkness compared to the solitary focus of what we do know. It could be said that anyone who tries to expand that illuminated zone of human knowledge, in any field, from science to politics, is an occultist. And if they are willing to share with the rest of the world any light of understanding they may discover, then they are an illuminist." This leads him to ask: "Perhaps the main duty of the occultist should be to diminish the scale and scope of their own occultism?"

However, contrary to what is common these days, Moore's interest in what lies beyond the real world does not translate into an escape from it. "The predominant mode of the fantastic in modern culture is simple escapism, which is a form of fantasy that not only do I believe is useless, but I also feel that in our precarious current situation, it is truly dangerous. We desperately need to think of solutions to this terrible situation, and not ignore the alarms because we are immersed in Middle-earth or the Marvel Cinematic Universe. As I have said on other occasions, escapism is a paper and celluloid fire escape that will never get anyone out of a burning building."

His unyielding and challenging stance against power also works here, in the realm of the extraordinary. "The important thing about any fantastic story, regardless of the impossible universe in which it is set, is that it somehow, even if only emotionally, relates to the world the reader knows and lives in. It must say something that is not only true in Narnia," he argues.

Thus, with the books of 'Eternal London,' he tries to "use fantasy as a lens through which to examine the latter half of the 20th century, as a way to understand how we have arrived here, in the fragmented and incoherent 21st century." He does not want to offer readers an "escape from this idiotic ring of Hell," but rather "entertaining and informative fun during which I hope to shed some light on our current situation and make some suggestions about where I think the emergency hatch might be."

Much of this idiocy comes from the omnipresence of superhero iconography in everyday life. Not only through blockbuster movies, but also in how they have ended up shaping citizens and, above all, their leaders. To talk about this, Moore takes one of his creations, 'V for Vendetta,' as a reference, which he refers to as "a property of DC/Warner Brothers that I have disowned and that I really do not want to see again or, if possible, ever think about again."

From the start, the writer has nuanced his support for movements that have adopted the Guy Fawkes mask as a symbol. "While Occupy used the mask in a way and for a cause that I wholeheartedly supported, I hastened to distance myself from Anonymous on the basis that, due to the movement's necessary anonymity, it was impossible to know where or from whom their hidden plans originated." Although protest movements "have become a necessary and vital phenomenon worldwide," he concedes, it would be "absurd and irresponsible" on his part "to support the political beliefs of anyone who owns a particular piece of Warner Brothers movie 'merchandise. After all, during the seemingly successful attempt to overthrow American democracy on January 6, 2021, there were smiling Guy Fawkes masks among the swastikas, Gadsden snakes, MAGA caps, and 'Arbeit Macht Frei' T-shirts ["Work Sets You Free," the slogan at the entrance to Auschwitz]. And of course, I have seen images of Tunisian students with Fawkes masks, just before the start of the Arab Spring designed by Anonymous that largely replaced a repressive government with another, ending up in the ongoing nightmare, even after Assad's departure, happening in Syria."

Moore realized what was happening when Channel 4 of British television took him to St. Paul's Cathedral in London to speak with Occupy protesters: "The vast majority of those wearing the masks had never read my original book, but had only seen the film adaptation with which, if anyone remembers, I wanted nothing to do, for which I refused to receive any payment and from which I removed my name from the credits."

The writer has never seen the resulting movie, "like the other film adaptations of my work," he assures. "But I have heard and read enough to know that it has gone from being a didactic fable written in the early years of the Thatcher administration to a confusing metaphor about 9/11 and American neoconservatives that manages to not mention the words 'fascism' or 'anarchy' even once and apparently reaches a happy ending with ghosts and fireworks. That film and the protest trend it triggered have no relation to me or my comic, of which I disown. I sincerely hope that my 'Eternal London' books are less unexpectedly explosive and more calm in their effects."

This distancing from the comic has given Moore a perspective that many consider prophetic. Thus, in 2013, he told a journalist that he thought "hundreds of thousands of adults lining up to see the new Batman movie was a worrying sign of massive infantilization, which is often a precursor to fascism." Furthermore, he noted that he found it "a pity that the audience of this amazing new century could not enjoy new ideas and characters, instead of clinging to franchises originally conceived to entertain 12-year-old children five decades ago."

What happened then was something that often occurs in Moore's life. "As always when asked a question about the field in which I have worked for 40 years and about which one might think I have some opinions, enthusiastic online superhero commentators now in their maturity, denounced me as an irrevocably angry hermit who gets angry about absolutely everything." Though repeated, it is no less irritating. "It takes much less effort to ridicule me as an old crazy man who certainly does not have the in-depth understanding of the superhero industry that they themselves possess," he comments wryly. Thus, he has no choice but to reaffirm: "This, I hope you understand, is one of the many reasons why I consider the superhero field a shameful waste of my time."

However, events unfolded: "The Brexit referendum, Trump's first term, and a far-right mess that ended with the overturning of the 'Roe vs. Wade' ruling, which eliminated women's reproductive rights and turned the United States into a medieval theocracy with Instagram, in addition to the televised invasion of the Capitol building by a mob with a portable gallows intending to hang Mike Pence and Nancy Pelosi."

"More than having supernatural predictive powers, I had simply commented on what seemed to me a likely political outcome of a genre originally intended for children, which focuses on simplistic ideas of moral certainty and for which brute force is the only form of conflict resolution," notes Moore. But reality continued its course: "There was Elon Musk's Iron Man costume on Halloween as a prelude to his Roman salutes at the inauguration of a convicted criminal who had openly expressed his intention to rule as a dictator." Moore's description of the X owner doesn't stop there: "A ketamine-fueled oligarch who likes to think of himself as 'the real-life Tony Stark'." That's where we stand. "And I am too exhausted to even say 'I told you so'."

Still, he blames and cites 'Watchmen,' of which he also disowns, as co-responsible for the massive emotional block that has brought us here. "This infantilization tends to make people expect reality to work like a comic, and for complex human problems to have conveniently simple comic-like solutions. As such, it provides an excellent breeding ground for fascism to take root and flourish." Another paradox, indeed. "This is how Siegel and Shuster's well-intentioned creation led to our current dilemma: while we wandered wide-eyed on our visit to the Batcave and the Avengers Mansion, a circus full of absurd Nazis wandered wide-eyed on their own visit to the Capitol building and ultimately the Oval Office."

He then denounces the 'ninth art' industry, stating that it is "largely controlled by untalented comic fans who are overpromoted, and by comic fans whose rich parents bought them a publishing house." They have adapted the industry "to their own interests as mature men, so that superheroines, once bland, now require a softcore pornographic sheen, and consequently, there are no longer basic level comics for children or younger readers, who are avoiding the medium in droves. This has led, as was predictable and obvious, to a situation where 'hardcore' comic readers are not only declining but literally disappearing, so that now they consist, at best, of about a hundred thousand increasingly betrayed and resentful middle-aged people. The industry staggers desperately with one absurd reboot after another, apparently because no one in it is capable of imagining or providing practical, new ideas. With each decade, this lack of ideas seems to be more pronounced."

Against this eternal return, the idea that conservative values are "a defiant punk rebellion against a liberal elite" that controls everything does not earn much respect from Moore. "In a world that, as far back as I can remember, has been almost entirely dominated by ideologies that are, at best, conservative, while being subjected to the moral values of a violent and intolerant Judeo-Christian sect from two thousand years ago, that is, if you'll pardon me, bloody laughable. And don't get me started on what this Labour government [Keir Starmer's] without character has just done to 'trans' and disabled people. In fact, on second thought, those disgruntled comic fans might be right. Maybe I am furiously angry all the time."

Or perhaps anger hides, in a final paradox, a solution: "We must come together as communities and protect each other, regardless of what our rulers throw at us, and we must go on the offensive with all the resources we have at hand: our music, our humor, our writings, our art, our protests, and our voices. We must love and we must fight." Moore signs off: "Love and struggle."