Three years later, their differences prevailed, sparking one of the most interesting intellectual conflicts in the history of thought. But in 1909, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were gazing together at the horizon from a ship that was about to arrive in New York. Mentor and disciple - 20 years apart - had been invited by Clark University (Massachusetts) to explain their innovative and unsettling theories. According to legend, the father of psychoanalysis asked his future enemy if he was aware that they were bringing a plague.

Although that was the case - a century later, concern for well-being and the desire for happiness are central - the anecdote is uncertain. "Freud said something more general: 'if they (the Americans) knew what they were bringing'," says psychologist and science journalist Steve Ayan, who now publishes in our country Architects of the Soul. From Vienna to the world: the invention of psychotherapy in the 20th century (Paidós). "He did not speak of a plague or make a self-destructive statement. Jung claims to have replied, 'they will soon know if they like it or not.' With this type of rumors, one must be careful. If the legend were true, it would be the only erroneous memory in Jung's autobiography."

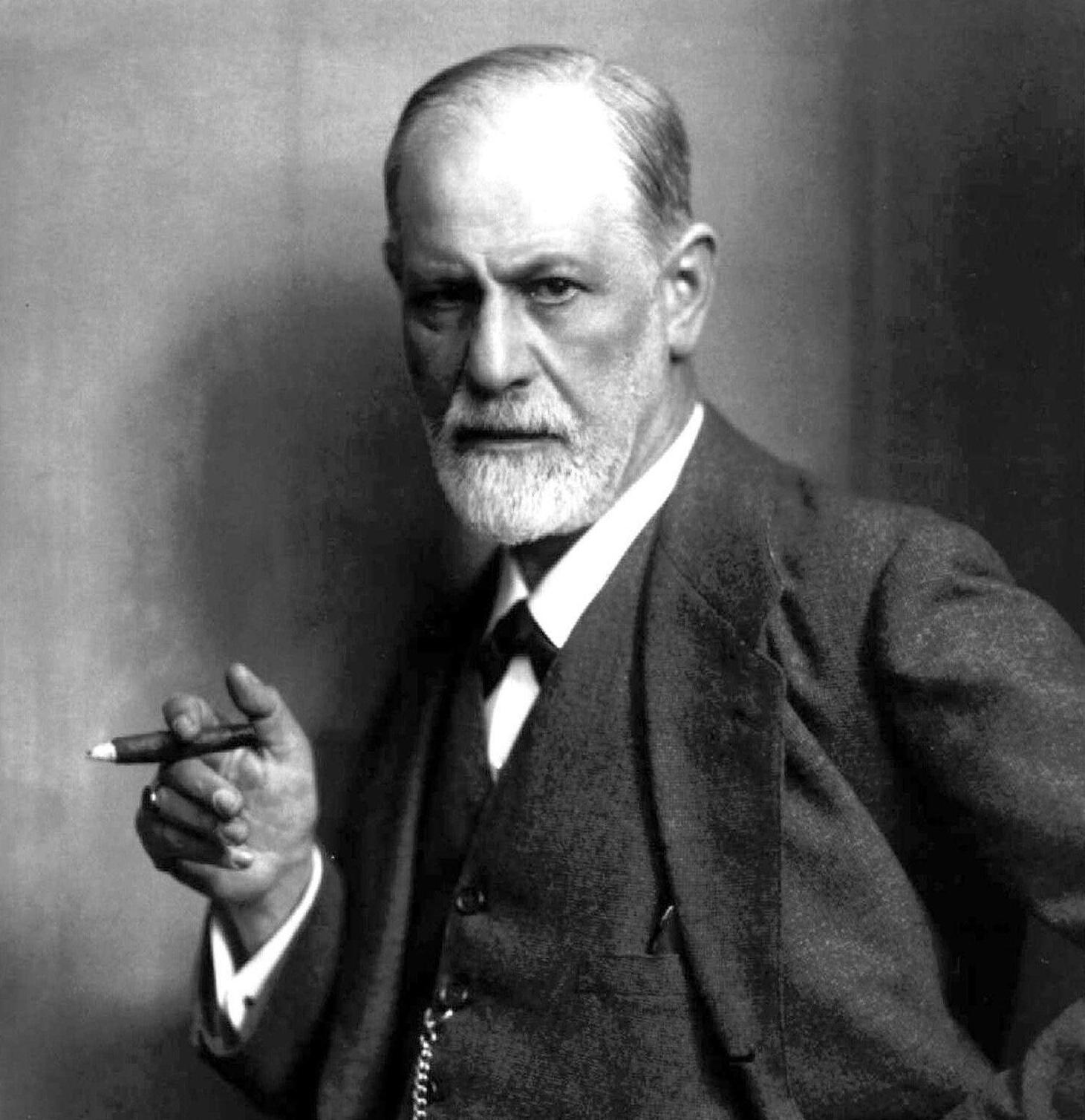

Between novel and essay - anecdote and fact - his interpretation of the origins of psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, clinical psychology, humanistic psychology, and behavioral psychology is dressed with a meticulous description of its most outstanding characters and the environments they inhabited. Not only Freud and Jung - Jung and Freud - but also the socialist Alfred Adler and Wilhelm Reich, who was obsessed with the orgasm. The first lines of the book are dedicated to the Wednesday meetings on Berggasse Street, number 19, in Vienna, filled with smoke from so many cigars, led by a Freud who had already published The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and where various issues were discussed from a psychoanalytic perspective.

The beginning of the enmity between the main characters is dated in 1913, but, as Ayan asserts, by 1912 the situation between Jung and Freud was already serious. "Ernest Jones, Freud's biographer, proposed that year to establish a secret committee to prevent the 'true psychoanalysis' from being exploited and mistreated by others. This circle included Freud, Jones, Hanns Sachs, Kalr Abraham, Otto Rank, and Sándor Ferenczi, and later also Max Eitingon. We only know about the secret committee from the letters they exchanged, which were published much later. But they could not prevent psychoanalysis from diversifying into many sub-theories by people like Horney or Reich, whom Freud vehemently opposed. Freud introduced a new type of thinking into the world, and although he wanted to control it, it slipped out of his hands and took on a life of its own."

Yes, Ayan has a certain fondness for the Austrian. But he has also read everything that offers information - in its original language, German - about the beginnings and development of one of the pillars of Western society: the promise of personal well-being. And also the construction of what we now consider defines the human being: hence his book is titled Architects of the Soul. In a video call interview, this author talks about "very important classics such as The Discovery of the Unconscious, by Henri Ellenberger, and Freud's biography by Peter Gay." "I found John Kerr's book, A Dangerous Method, very useful, as well as the work of the German historian and sociologist Michael SchröterAuf eigenem Weg, which I don't know if it's available in English," he details.

He also delves into the myths of the founders of what we now broadly know as psychotherapy. "New variants, splits, and alternative proposals, over time, gave rise to an unmanageable network of hundreds of therapeutic methods," he emphasizes in the book. "A number that continues to grow," he insists, a phenomenon that, according to this author, is motivated "by objective reasons related to the progress of clinical psychology and psychiatry. And the fact that psychotherapy continues to obey the economic logic of supply and demand."

For Ayan, "there is a general cliché: to believe that Freud and the psychoanalysts really saw, as if they had X-ray glasses, what truly drove people." He finds it a popular myth: "Most of popular psychology still plays with this idea today. However, scientific psychology has moved away from it. Nowadays, scientists see the unconscious and consciousness as closely intertwined, not as separate realms. And knowing what happens in the unconscious is highly speculative. Most of the early psychotherapists benefited from exaggeration: they pretended to know much more than one could imagine. This is true for Freud, but also for Adler, Jung, Reich, Perls, and many others."

In his novel-essay, Ayan does not lose sight of the current context. That today, for example, the analysis of mental problems is much more differentiated than in the past: that there is no longer a single neurosis but "a wide range of disorders and syndromes with numerous subtypes." In the manuals used today, depression alone comprises almost 30 variants, and the same goes for persistent complicated grief. But Ayan continually returns to the beginnings because he believes that "if one has a better idea of what those times were like and what these people were like, one can gain a better understanding of what is really behind the theory." "It also helps prevent the elements of the theory from sounding strange or absurd. If one knows what Viennese society was like at the beginning of the 20th century, one can better grasp the theory," he suggests.

Let's read an excerpt: "The year 1902 is coming to an end, and Vienna, the proud capital of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, is bursting at the seams. Construction has been ongoing for some time. The streets, especially east of the canal, in the Leopoldstadt district, are crowded with newcomers from all corners of the Habsburg Empire, from Bohemia and Moravia to Bucovina and Transylvania. Week after week, hundreds of people, many of them Jewish, arrived in the Danube metropolis fleeing poverty and persecution in search of a better life. According to the 1869 census, Vienna's population was around six hundred thousand inhabitants (...). In the 30 years since then, the population has tripled. Soon, two million souls will be reached."

The city became an "experimental field" that benefited various disciplines: "The avant-garde of art, philosophy, and science are trying out new forms of thought and expression that break with a tradition considered outdated." Vienna is also a "hotbed of ideas": painters like Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, composers Arnold Schönberg and Gustav Mahler, architects Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos, journalist Karl Kraus, and writer Lou Andreas-Salomé, who was Freud's disciple, that is, also a psychoanalyst.

One of the first turning points achieved by these pioneers was "overcoming the dogma that every illness, even mental, must have a physical cause," Ayan recounts in his book. "They believed that anxieties, compulsions, restlessness, unexplained pains, or melancholy could not be attributed to brain anomalies or organic dysfunctions. Their hypothesis was that, at the origin of the symptoms, there were ideas, memories, feelings, and thinking patterns of which individuals were not necessarily aware." This was a "revolutionary idea that shed an entirely new light on the internal functioning of the being."

But Ayan warns that "it is dangerous to judge what happened 100 years ago from a current perspective." And also that, at this point, there is a need to return to Freud, but knowing that he always had two sides: that of the genius and that of the madman, the master and the disturbed, or as Ayan describes, "the genius and the charlatan." "It has always been like this, even then there was a tendency to worship Freud, by some, who said he was 'their master.' Others felt a deep animosity, so when you read his biographies you get a double face: that of the admirers and that of the detractors. And this makes it difficult to understand these individuals. By the way, recently a famous German psychoanalyst said he couldn't tell if Freud, in Architects of the Soul, was describing himself as a charlatan or as a genius. And this is something that I found very important to convey, the double face, because Freud really introduced an intellectually and historically fundamental approach, and this is his brilliant part, but he was also very interested in promoting himself, as well as his school of thought."

So much so that, in his previous office on Bergrasse Street and even before the start of the 20th century, Freud used to seat his five sisters in the waiting room "to make it seem like he had many patients." Ayan says that "he was very stubborn, egocentric, and irascible." "And not the type of person you could get along with for a long time if you had your own ideas about how the mind and therapy worked." Hence the enmity between him and Jung was irreconcilable and even intensified over time. Jung had reservations about Freud's emphasis on sexual desires and libido.

"Under the premise of the time that desires must be repressed, it can be said that the way they are repressed marked the difference between illness and normality, but normal people also repress because they have desires that are not pleasant. If not, we would have sex with practically anyone and argue with anyone as well. But Jung had a very different idea, he believed that subconscious processes have their function: they arise to show us something," reflects the author.

This month, for the first time, one of his fundamental works has been published in Spanish, The Black Books (editorial El Hilo de Ariadna): seven volumes of intimate writings by the Swiss -even his dreams-, in addition to his figurative works in a sort of "experimentation," says his editor, Sonu Shamdasani, which show the core of his cosmology. Far from Freud, for now, whose texts would serve as notes for the Red Book, one of his most famous works that was not published in English until 2009.

All of this seems important to Ayan, not only because today "psychotherapy is experiencing an unprecedented boom" but also because he believes that "psychology as a field, whether popular or academic, is very forgetful of its past." He is glad that "paying attention to oneself and one's mood permeates all areas of life" - he believes that "increased sensitivity allows problems to be detected earlier and counteracts stigmatization" - but he also considers that, in these times, "many simply unpleasant feelings are perceived as pathological."

The Search for Meaning

Hence he also advocates for other intellectuals, such as the Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl and, especially, his book Man's Search for Meaning (reissued in 2024 by the Herder editorial), where he recounts his own experience in a concentration camp. His famous quote - also repeated by Ayan - states that "one can endure any how if there is a why." In Architects of the Soul, the author proposes to use, in 2025, one of the techniques that Frankl implemented almost a century ago, known as dereflexion, that is, "to act instead of thinking, to engage instead of grumbling." Ayan points out: "The therapeutic boom tends to provoke the opposite: hyperreflection in which thought constantly revolves around itself. All of this finds its expression in a language of vulnerability that is increasingly widespread, filled with blocked energies, repressed traumas, and inner children."

Another significant change between past and present psychotherapy would be the relationship between patient and therapist. Or, as is often said now, between client and therapist. "Psychology has evolved from its origins from eminence to evidence, from a series of charismatic figures who founded a theory and a method to a movement that seeks evidence, that is, what really works," describes Ayan. "Currently, many people go to therapy and start by saying that 'they have many difficulties in life and don't exactly know where they come from, that they believe it is mainly other people who do not accept them as they are.'" And the goal, in the end, is simple: "To discover one's own self without feeling ashamed but by realizing things and trying to change what is necessary."

In general, the drift of psychotherapy has not gone too badly, according to this specialist. He believes that "therapists have realized that theoretical explanations alone are not enough to treat disorders and, instead of analyzing internal conflicts coldly, they prefer to emphasize the emotions involved."

Today, the main goal of entering therapy, whether behavioral, psychoanalytic, or transactional (which emphasizes that within one is also their child self and adolescent self), is "to create positive experiences to facilitate therapeutic dialogue and establish healthier habits." "Current therapists are, therefore, much less dogmatic or prejudiced than the pioneers of the past, and it is no coincidence that the vast majority are women. They no longer seek to cure psychic discomfort by presenting unquestionable truths, as Freud, Adler, or Jung did. On the contrary, they try, with a more pragmatic spirit, to support their clients to help them better face their daily lives."

And this is how everything that can be useful in this regard ends up being welcomed, because in reality "the search for the origin of discomfort has taken a back seat." More important than the why of things would be what to do with them, with our burdens, and how to find effective remedies for the problems that arise in everyday life. As long as there is a real problem because, as Ayan denounces, "we are accustomed to pathologizing sadness" or any other common and normal emotion.

Not everything is solved in therapy, and not everyone needs it. But those who need it and decide to undertake it have the interesting adventure of getting to know themselves much better.