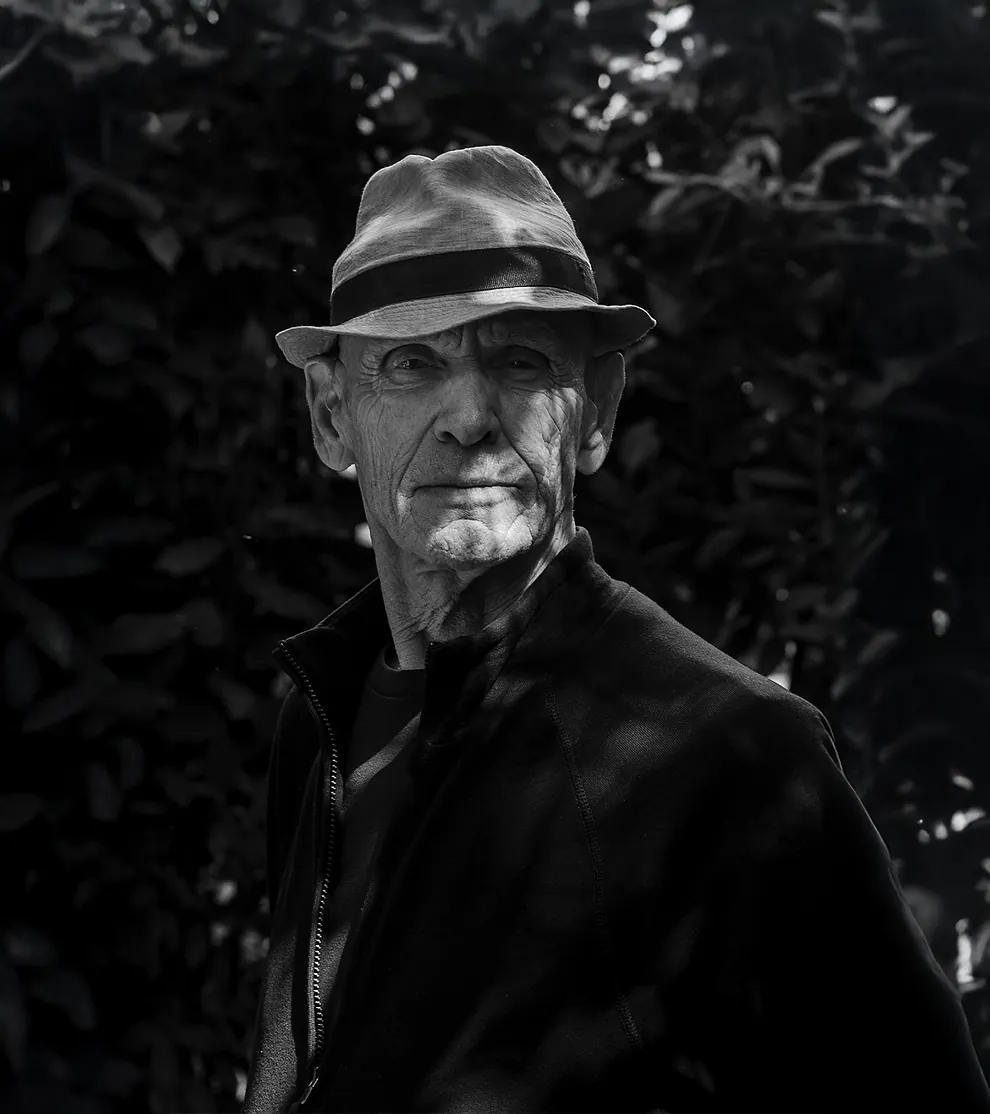

Joel Meyerowitz (New York, 1938) appears in the luxurious lobby of the Rosewood Villa Magna in Madrid with his felt trilby hat, a black knit jacket, and his digital Leica hanging on his shoulder. Almost in a whisper, he greets everyone present. Like a strange entity in a place that does not belong to him. Like a man from another time surrounded by contemporary opulence. Like the great street photographer enclosed within four walls. And yet, none of that seems to matter to him.

He walks down the hallway and sits in a room with translucent walls. He places his hat and Leica on the table and politely asks for the music to be lowered so that the conversation can flow smoothly and not interfere with his hearing aid. "Now we can begin." So be it. This 87-year-old man is living history in the world of photography. Many of the iconic images of the streets of 60s and 70s New York, from his native Bronx to Lower Manhattan, belong to him. He also captured the aftermath of the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in 2001, being one of the few professionals who managed to bypass the security cordon to document the tragedy. And a series of 200 snapshots that were born during an extensive road trip through 10 European countries in the 60s, when the continent was just beginning to recover from the aftermath of World War II.

It is precisely that exhibition, Europe 1966-1967, that can now be seen at the Centro Cultural de la Villa in the center of Madrid, as part of PHotoEspaña 2025, which has also awarded the New Yorker the prize for this edition for his extensive career. In that exhibition, as in the photographer's life, Malaga plays a key role. It was there where the photographer settled for several months during his European journey, embedded among Andalusian families, to discover the life of the neighbors in the developmentalism that Franco's regime had entered.

"There I discovered myself as an artist. I was only 28 years old but I began to understand my own temperament. I was alone every day, I shot 750 rolls of film, half in color and half in black and white, and I didn't see them all year. So, in a way, I worked based on a kind of trust and that's how I understood who I was," he explains in a monotonous and calm tone. And he continues: "In the 60s, life had a basic and normal simplicity, today everything is exaggerated by the Internet, money, and tourism. There were no ships arriving in Malaga unloading 3,000 people at once in the city, you could walk the streets with a certain tranquility. Although Franco's regime was restrictive, there were conversations on the street, there was no need to adapt to tourists."

In those snapshots of flamenco clubs and cafes, of community life, color was already beginning to seep in, one of the great contributions of the American to the history of photography. He was one of the pioneers in using that technique when black and white was the prevailing tone. Meyerowitz's colors as a memory of streets that today do not resemble them in essence or form. "There is still life on the street, but attitudes have changed, just like clothing and values. That life is interrupted by human interaction with virtual reality."

Sidewalks are no longer a meeting place, a gathering place, they are a transit area. Almost like a runway surrounded by technological progress. "People are always looking at their phones to see news, photos... Street life is no longer a playful human exchange, everything is a distraction. People only look up to see if a car is going to run them over and then go back to their phones." He pauses and continues: "With the internet, everyone wants to show their face, body, writings, photos, or whatever in the hope of getting more followers and making money. They want to be famous for being famous, they are interested in being known. When I started taking photos, I didn't want to be recognized, I couldn't help but take them. I liked to capture moments of beauty that were there and fading away. I feel that kind of tacit conversation with the street has been broken."

In 1976, Meyerowitz was warned of this rupture when he was commissioned an advertising campaign in a scientific magazine. The photographer flew to Colorado to learn about the computer division that Hewlett-Packard was beginning to develop in the United States. And in front of a large central computer, a 38-year-old engineer warned him of what was to come. "He told me that someday, he didn't know when, we would all be connected and able to communicate instantly. In 1976, Apple didn't even exist," recalls the New Yorker.

According to the photographer, the problems we face today are not very different from those of five decades ago. Wars have changed their stage but have resurfaced in our society. Racial segregation has resurged as one of the social debates in the United States - and worldwide - especially after Donald Trump's victory. "We only have different protagonists and different needs," Meyerowitz adds, who now lives in London, where he has participated in street protests against Brexit. As he did in New York after the re-election of the current President of the United States. The street, always the street. "My wife and I went out to protest not only to take photos, we wanted to be part of it. It is important to take risks to be part of a historic moment. It's a double game: you go to support something you believe in and maybe you find some photographs."

Having spent six decades and at 87 years old, photography still remains the anchor of his life. The Leica that now rests on the table still accompanies him every day when he leaves the house. Without exception. And in the near future, he still has a project ahead of him. "It will be something completely different, distorted, but I can't tell you more because I'm not allowed to," he announces without revealing much more. In addition, his editor intends for him to develop a book with his unpublished photographs from the 60s. "It is really interesting to review your work, but above all, it is interesting to see who you were when you started and who you are today."

Before leaving, Meyerowitz bids farewell with a "I hope we meet again" to once again disappear into that ecosystem that is not his own. Like a photo that has never been taken.