"Ambitious, vain, and daring," this is how Léon Degrelle is described in the pages of the dramatis personae of The Last Flight, by Fernando Castillo (Renacimiento). Later, Castillo expands on this description: "He was tall, handsome, and charming, and he was educated or, at least, well-read. He was also a storyteller, and his memoirs are so full of lies that there are moments when he makes you laugh," the author tells EL MUNDO. "He was a risk-taker, one of those characters who put everything on the line every time and always managed to get an extra life." "He was a swindler, bankrupted a hundred times and always found someone to bail him out, to pass on his debts." "I don't think he was born to be a Nazi; for many years, he was a Christian conservative, more or less a Walloon nationalist... But he became an uncompromising fascist and never regretted it. He wasn't like Jean-Marie Le Pen, who tried to modernize the meaning of the word fascist. Degrelle talked about Hitler and the SS, denied the Holocaust... He had no complexes." "He was a womanizer. When he wrote in his memoirs about his desperate escape through Denmark and Norway, he dedicated paragraphs and paragraphs to how much he liked Scandinavian women." "He was a sinister man. And I don't mean sinister as in fascist, I mean something more."

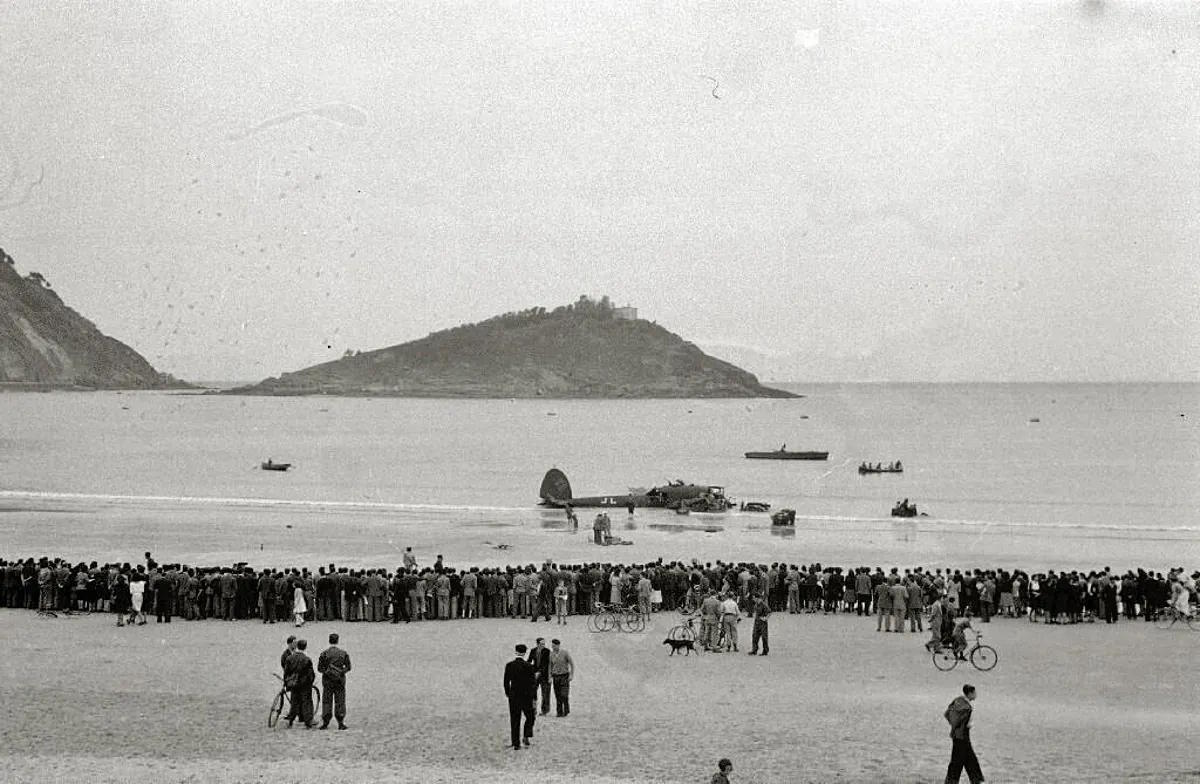

None of those flights was as unusual as Léon Degrelle's, who landed in the waters of La Concha Bay at six in the morning on May 7, 1945, a week after Adolf Hitler's suicide and a day after Germany's surrender. 80 years ago. The plane was a Heinkel 111 H-23, a variation of a bomber adapted for transporting paratroopers, with the Balkenkreuz, the cross of the German armies, painted on its fuselage. Its splashdown woke up the entire city. In San Sebastián, there was a rumor that Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer were on board, but soon the identity of the crew was revealed: Albert Duhringer, pilot; Benno Epner, his assistant; Gerhard Stride, mechanic; Georg Kubel, telegraphist; Robert du Welz, SS captain; and Léon Degrelle, the general of the Walloon Division, the favored son of the II Reich, the man whom Hitler said embodied the son he never had. Well: that's what Degrelle claimed Hitler said, but Fernando Castillo suspects it was one of his fantasies.

How did Degrelle arrive in San Sebastián? His escape began in June 1944, the last time he was in Brussels, his city, where he buried his brother Edouard, a pharmacist murdered in a Resistance attack. In the following months, Degrelle was on the Eastern Front with the Walloon Division and in the retreating Axis courts: Baden Baden and Sigmaringen (the refuges of French collaborators after the liberation of Paris), Milan, Berlin... On April 20, in the territory that is now northern Poland, he gathered his troops, a greatly diminished group of French-speaking Belgian volunteers who, since June 1943, had the status of Waffen-SS. He told them that the war was lost for the Axis, gave them false civilian documentation, and advised them to pass as forced laborers for the Nazis. Good luck.

Degrelle and his assistant, Robert du Welz, passed through Lubeck and Kiel, Baltic ports in Germany. On the night of Hitler's suicide on May 2, they jumped to Copenhagen. "While many of his comrades were committing suicide, Degrelle had the survival instinct to attempt one more impossible leap," Castillo recounts. During the war, Denmark had experienced a relatively gentle occupation. The Jews of Copenhagen were not sent to extermination camps, the cities were not bombed, and Degrelle thought that Christian X's kingdom could become a northern Switzerland. However, the British entered Denmark on May 5, and the Belgian Nazi had to escape at the last moment, boarding a minesweeper to Oslo.

In Norway, there were 300,000 German soldiers who would not receive the surrender order until the seventh day and who still had some control over Oslo. They were led by a particularly hated Gauleiter, Josef Terboven, and supported by a collaborationist prime minister with a hardline stance, Vidkun Quisling, even fiercer than Degrelle. Together, they sheltered the Belgian SS general for two days and revealed that a Heinkel 111 H-23 and its crew were ready for the final escape at the Gardermoen airfield, the current Oslo airport.

"Degrelle later wrote that this was the plane that Albert Speer had at his disposal, but that's another of his lies," Castillo explains. "Speer traveled in a Focke Wulf, much more modern and comfortable than the Heinkel. Nevertheless, it's incredible that Degrelle achieved the impossible and escaped, something that neither Quisling nor Terboven managed... Do you know which countries repressed collaborationists most harshly after the war? Belgium and Norway."

The Heinkel 111 H-23 was said to have a range of 2,300 kilometers, and the closest point in Spain from Oslo is 2,200 kilometers away. However, pilot Duhringer couldn't fly in a straight line. The Heinkel had to navigate blindly, spotting lights, guessing that some were from Hamburg and others from Bordeaux. Degrelle wrote in his memoirs that he flew over Paris and saw the lights of cars and celebrations of his enemies, but Castillo believes that was another fantasy. Before the night ended, the fuel ran out while the plane was flying over Biarritz, so Duhringer glided until crossing the border and making an unprecedented splashdown in the bay of San Sebastián. If this operation had taken place in the waters of San Juan de Luz, Degrelle would have been handed over by France to the Belgian resistance fighters who would undoubtedly have executed him.

Degrelle's Heynkell, in San Sebastián, on May 8, 1945.FUND. KUTXA

What did Léon Degrelle find in San Sebastián? Firstly, a few fractured bones that led him to the General Mola Military Hospital in the Egia neighborhood. He was dressed in uniform. "The rest of the crew came out unscathed," Castillo recounts. During his recovery, Degrelle's Spanish friends, led by José María Finat y Escrivá de Romaní, Count of Mayalde and future mayor of Madrid, took him in a car and hid him. "No one did something like that in Spain in those years without the regime's permission," Castillo explains. But the dictatorship played dumb. When Belgium requested the extradition of its most hated son, Spain claimed not to know his whereabouts. "And then, unofficially, they offered him as a bargaining chip: we give you Degrelle, but you help us normalize our situation in Europe and forget our past friendship with the Reich," Castillo explains. Belgium took offense and withdrew its ambassador.

It didn't matter. Degrelle survived as best he could in the years 1946 and 1947, when Francoism was most fragile, and then did what he did best: seduce, deceive, enrich himself, go bankrupt, get rich again, show off, and recount his adventures to captivate a renewed audience from the 1970s onwards, when the new fascism entered Europe's political landscape. He had a white SS general's uniform made, as if he were living in a play. And his companions on the flight from Oslo to San Sebastián? The Germans returned home. They were young and had no crimes to answer for.