Of all the surrealists of surrealism, Salvador Dalí was the most genuine, the most convinced, the most extreme in staging, the best projected. He joined the group in 1929, five years after André Breton set this adventure in motion by publishing the First Surrealist Manifesto and splitting the waters of painting, poetry, and cinema in Europe. Dalí brought the endorsement of his artistic work, some minimal performances, and collaboration in the script of the film Un Chien Andalou, by Luis Buñuel, which they premiered in Paris (1929) accumulating the sparkling enthusiasm of a scarce and furtive audience. When Breton met Dalí after hearing Paul Éluard's enthusiasm about the artist for whom his wife had left him, he offered him immediate entry into the tribe.

Dalí was five steps ahead of any early surrealist. He had no mold, no rule, no obligation, no god, no master. In that same year he fell in love with Gala in Cadaqués, when she traveled with Paul Éluard (her husband until then), and with René Magritte, and with the Belgian journalist Camille Goemans... Upon returning to Paris after the summer, Dalí settled with Gala in their apartment at 7 rue Becquerel. And he began his sidereal adventure in surrealism and beyond, as Salvador Dalí and Gala were not satisfied with just surrealism. That was a beginning, but it would be regrettable if they also saw it as an end. Making money and being famous was more stimulating.

Dalí's fame grew at an incredible speed in Paris, in the European surrealism circles, and also in New York. The 1930s were a time of great effervescence and of the clear positioning of surrealists in favor of communism and the USSR regime. Everyone (or almost everyone), except Dalí. This caused the first suspicions of Breton and the other leaders of the group (Louis Aragon, Benjamin Péret, Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, René Crevel...). They did not understand why he did not join the pro-communist front. Remaining on the sidelines was seen as frivolous. Hitler and Mussolini were gaining ground in Europe, so indifference was a distortion. He was accused of defending "the new and irrational nature of the Hitlerian phenomenon." Dalí insisted that surrealism could exist as an artistic phenomenon, separate from activism, far from politics. This was even less liked and he lost prestige among the comrades of the group. In 1934, he was subjected to a "surrealist trial" that resulted in his expulsion from the movement. A dismissal to which Dalí responded with the most arrogant and effective of challenges: "I am surrealism." He was not wrong.

Outside the group, but more striking than when he belonged, 1936 was the year of Dalí's ejection into the sky of himself. During this time, he worked on several key paintings of his surrealist production: Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of the Civil War), The Great Paranoiac, The Dream Places its Hand on a Man's Shoulder, Two Heads Filled with Clouds, or Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra. It was the year of the murder in Granada of his best friend (later despised), Federico García Lorca. He never did anything to maintain the memory of the depth of that friendship. And 1936 was also the year of the major surrealist exhibition at the MoMA in New York, Fantastic Art, Dadaism, Surrealism, where Dalí had several pieces on display and met Walt Disney. It was also the year of the surrealist exhibition in London, where the artist from Ampurdán was invited to give a lecture, which he delivered wearing a diving suit with a helmet. Dalí's creative process was at its peak. He had a patron, the American poet and art collector Edward James, for whom he created one of the iconic pieces of the movement: the Lobster Telephone. In this feverish moment, Dalí embarked on his first trip to New York with Gala. Everyone indeed recognized him as the most resounding asteroid of surrealism. Nothing favored him more than being expelled from the group.

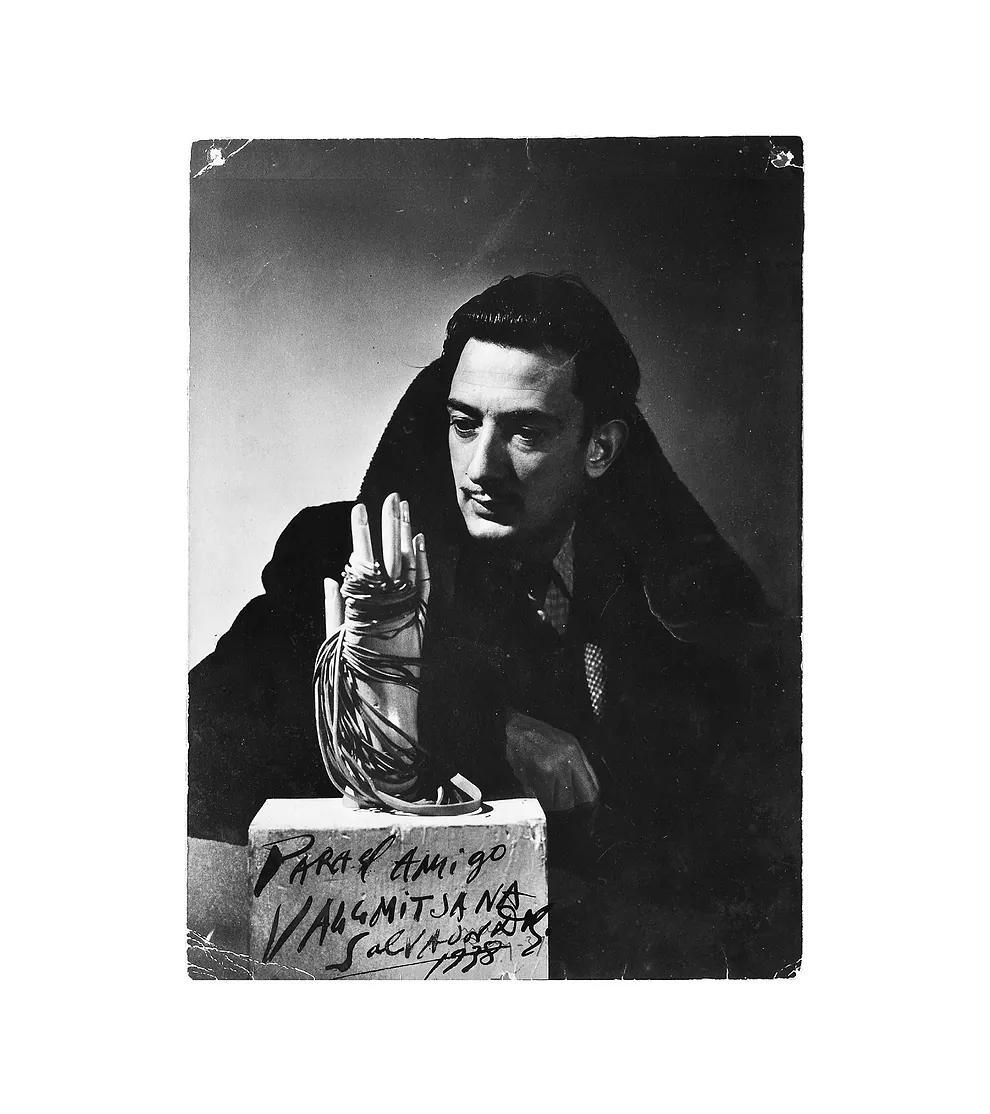

In the winter of 1936, the photographer Man Ray, one of the commanders of the movement, invited him to his studio in Montparnasse for a portrait session with Gala. The painter was aware of the importance of the image. Photography was part of his promotional strategy. He agreed to the proposal, and one morning in February, they both arrived at the agreed time, before 1:00 p.m. There they posed as Man Ray suggested. Together, not looking at the camera, as if indifferent, well-dressed and showing the cold of winter, leaning on a plinth topped with a mannequin hand surrounded by elastic bands. Now separately. And together again... From the session came two portraits of each of them and two couple portraits. Weeks later, Man Ray called Dalí to let him know that he had the copies. They met at Café de Flore in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Man Ray showed him the portraits and gifted one of the copies to the painter, signed in pencil (as was customary in many of his autographed pieces). It was one of the photographs he took alone, with the same crossed hand of the mannequin but placed on a different base. A Dalíesque photograph in which the artist appears with an elegant coat with a fur collar, jacket, shirt, tie, and a distinctive little mustache that was starting to become a trademark of the house. Dalí left the café with the photograph under his arm.

It could be one of the thousands of images Salvador Dalí posed for, but this one has a particularity. A distinctive hallmark. In truth, there are two: it is signed by both creators. On the base where the mannequin's hand rests, it is possible to read in pencil: "Man Ray 1937." And above this signature, without invalidating it: "For the friend Vallmitjana. Salvador Dalí 1938." Everything seems to point to the same thing: it is the only photograph in the world signed by both, two of the most relevant creators of the surrealist movement. The photo historian Publio López Mondéjar, a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and author (among other studies) of the History of Photography in Spain, says this: "Of the portrait dedicated to two hands, which Vallmitjana kept for so many years, I only know that it exists. Almost no one has seen it, and I also do not know who preserves it. If it is the only copy -and it will be- signed by both, it surely has extraordinary value, especially in a society that craves the exceptional and the rare so much. Which, in my modest opinion, neither adds nor subtracts from the artistic value of the piece nor makes Dalí's or his friend Man Ray's work more or less important."

Detail of the portrait where Man Ray's pencil signature and Dalí's (above) in India ink can be appreciated.

Of all the surrealists of surrealism, Salvador Dalí was the most genuine, the most convinced, the most extreme in staging, the best projected. He joined the group in 1929, five years after André Breton set this adventure in motion by publishing the First Surrealist Manifesto and splitting the waters of painting, poetry, and cinema in Europe. Dalí brought the endorsement of his artistic work, some minimal performances, and collaboration in the script of the film Un Chien Andalou, by Luis Buñuel, which they premiered in Paris (1929) accumulating the sparkling enthusiasm of a scarce and furtive audience. When Breton met Dalí after hearing Paul Éluard's enthusiasm about the artist for whom his wife had left him, he offered him immediate entry into the tribe.

Dalí was five steps ahead of any early surrealist. He had no mold, no rule, no obligation, no god, no master. In that same year he fell in love with Gala in Cadaqués, when she traveled with Paul Éluard (her husband until then), and with René Magritte, and with the Belgian journalist Camille Goemans... Upon returning to Paris after the summer, Dalí settled with Gala in their apartment at 7 rue Becquerel. And he began his sidereal adventure in surrealism and beyond, as Salvador Dalí and Gala were not satisfied with just surrealism. That was a beginning, but it would be regrettable if they also saw it as an end. Making money and being famous was more stimulating.

Dalí's fame grew at an incredible speed in Paris, in the European surrealism circles, and also in New York. The 1930s were a time of great effervescence and of the clear positioning of surrealists in favor of communism and the USSR regime. Everyone (or almost everyone), except Dalí. This caused the first suspicions of Breton and the other leaders of the group (Louis Aragon, Benjamin Péret, Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, René Crevel...). They did not understand why he did not join the pro-communist front. Remaining on the sidelines was seen as frivolous. Hitler and Mussolini were gaining ground in Europe, so indifference was a distortion. He was accused of defending "the new and irrational nature of the Hitlerian phenomenon." Dalí insisted that surrealism could exist as an artistic phenomenon, separate from activism, far from politics. This was even less liked and he lost prestige among the comrades of the group. In 1934, he was subjected to a "surrealist trial" that resulted in his expulsion from the movement. A dismissal to which Dalí responded with the most arrogant and effective of challenges: "I am surrealism." He was not wrong.

Outside the group, but more striking than when he belonged, 1936 was the year of Dalí's ejection into the sky of himself. During this time, he worked on several key paintings of his surrealist production: Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of the Civil War), The Great Paranoiac, The Dream Places its Hand on a Man's Shoulder, Two Heads Filled with Clouds, or Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra. It was the year of the murder in Granada of his best friend (later despised), Federico García Lorca. He never did anything to maintain the memory of the depth of that friendship. And 1936 was also the year of the major surrealist exhibition at the MoMA in New York, Fantastic Art, Dadaism, Surrealism, where Dalí had several pieces on display and met Walt Disney. It was also the year of the surrealist exhibition in London, where the artist from Ampurdán was invited to give a lecture, which he delivered wearing a diving suit with a helmet. Dalí's creative process was at its peak. He had a patron, the American poet and art collector Edward James, for whom he created one of the iconic pieces of the movement: the Lobster Telephone. In this feverish moment, Dalí embarked on his first trip to New York with Gala. Everyone indeed recognized him as the most resounding asteroid of surrealism. Nothing favored him more than being expelled from the group.

In the winter of 1936, the photographer Man Ray, one of the commanders of the movement, invited him to his studio in Montparnasse for a portrait session with Gala. The painter was aware of the importance of the image. Photography was part of his promotional strategy. He agreed to the proposal, and one morning in February, they both arrived at the agreed time, before 1:00 p.m. There they posed as Man Ray suggested. Together, not looking at the camera, as if indifferent, well-dressed and showing the cold of winter, leaning on a plinth topped with a mannequin hand surrounded by elastic bands. Now separately. And together again... From the session came two portraits of each of them and two couple portraits. Weeks later, Man Ray called Dalí to let him know that he had the copies. They met at Café de Flore in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Man Ray showed him the portraits and gifted one of the copies to the painter, signed in pencil (as was customary in many of his autographed pieces). It was one of the photographs he took alone, with the same crossed hand of the mannequin but placed on a different base. A Dalíesque photograph in which the artist appears with an elegant coat with a fur collar, jacket, shirt, tie, and a distinctive little mustache that was starting to become a trademark of the house. Dalí left the café with the photograph under his arm.

It could be one of the thousands of images Salvador Dalí posed for, but this one has a particularity. A distinctive hallmark. In truth, there are two: it is signed by both creators. On the base where the mannequin's hand rests, it is possible to read in pencil: "Man Ray 1937." And above this signature, without invalidating it: "For the friend Vallmitjana. Salvador Dalí 1938." Everything seems to point to the same thing: it is the only photograph in the world signed by both, two of the most relevant creators of the surrealist movement. The photo historian Publio López Mondéjar, a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and author (among other studies) of the History of Photography in Spain, says this: "Of the portrait dedicated to two hands, which Vallmitjana kept for so many years, I only know that it exists. Almost no one has seen it, and I also do not know who preserves it. If it is the only copy -and it will be- signed by both, it surely has extraordinary value, especially in a society that craves the exceptional and the rare so much. Which, in my modest opinion, neither adds nor subtracts from the artistic value of the piece nor makes Dalí's or his friend Man Ray's work more or less important."

Detail of the portrait where Man Ray's pencil signature and Dalí's (above) in India ink can be appreciated.