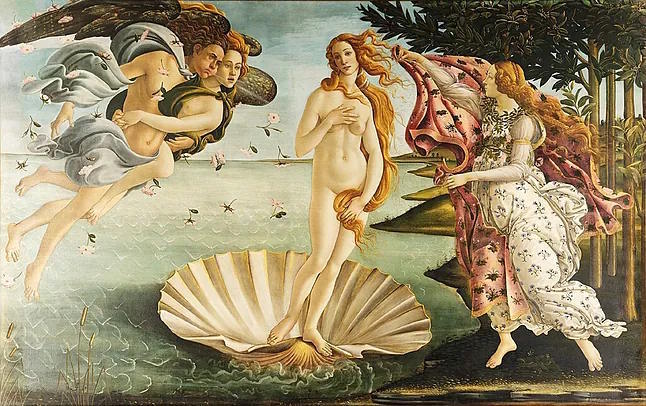

The Birth of Venus (1485) by Sandro Botticelli is not (just) one of the most beautiful paintings on classical mythology. It is not even just the first erotic (and non-biblical) nude painted since Antiquity in an evocative homage to Praxiteles' Aphrodite of Knidos. It is a painting about an impossible love, about a fascination that transcends death. At least, that is the prevailing rumor in Art History. The stunning Venus, almost life-size, is none other than Botticelli's platonic love: Simonetta Vespucci, married at 16 to the aristocrat Marco Vespucci. Although there are no documents or records where Botticelli confessed his passion, speculations - reinforced by the artist's own works - point to a painter secretly captivated by the "beautiful Simonetta," as she was known in the court of Florence, where she dazzled even the Medicis. Why else would he continue painting her years after her premature death at 23? Why do most of his Madonnas and goddesses seem to have Simonetta's face?

The Birth of Venus, created almost 10 years after the young woman's death from tuberculosis, is a clear courtly love declaration with a mythological alibi more than literal: Simonetta was born in Porto Venere [Port of Venus], on the Ligurian coast, "where furious Neptune strikes the rocks / There, like Venus, she was born among the waves," wrote the poet Angelo Poliziano. "Was she a woman who obsessed or fascinated him to the point of turning her into a goddess?" rhetorically wonders art historian and Daily Telegraph journalist Nick Trend, author of Love Through Art (Cinco Tintas), a delightful volume that, as its subtitle states, is A walk through eternal, secret, chained, burning, and unrequited loves.

In case there were doubts about Botticelli: of all the churches in Florence, he requested to be buried in the Ognissanti church, at the feet of Simonetta's tomb. 34 years had passed since her death.

"How many songs has love inspired? But what about art? What do images tell us about love? It's not something that is talked about much..." Trend asks, again rhetorically. That was the starting point of an original book with over 70 paintings that hide the feelings of Raphael, Caravaggio, Georgia O'Keeffe, Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo...

"Love songs aim to express feelings. But a significant part of visual Art History deals with eroticism, with nudity as a genre in itself. However, there are many examples of paintings that express real feelings because artists are portraying their lovers. And that makes the image even more powerful," compares Trend. How does an artist in love paint their model? Is there more passion, turmoil, or delicacy in their brushstrokes? The answers are as varied as the personalities and egos. But what is interesting, Trend emphasizes, is that when looking at an erotic nude, the viewer takes on a voyeur role, while in front of a lover's portrait, they step into the artist's shoes: "The painter's deepest feelings are reflected. In a way, you become the artist because you are looking at the model, and she looks back at you."

Nick Trend, who was part of the curatorial team at the National Gallery in London for years, was working on a text about 17th-century Dutch painting. One day, alone in National Gallery's Room 22, he was struck by Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels (c. 1654-1656), painted by Rembrandt during one of the most terrible periods of his life, in the midst of bankruptcy. "There was desire and admiration... I felt that connection that Rembrandt must have had when he painted the portrait. That room is full of some of his best paintings, but it was always that painting that exuded a different presence and power," recounts the historian.

Who was Hendrickje? Rembrandt's second great love, who brought back his joy years after the death of his wife Saskia. However, he never married his young lover (20 years his junior) because, according to Saskia's will, he would lose the inheritance if he remarried. They did have a daughter. "She was going to be a single mother in 17th-century Holland, which made her a social and religious outcast. But she stayed by Rembrandt's side, even in his worst moments," explains Trend. He refers to the economic bankruptcy, loss of clients, forced move to a cheap house... But Hendrickje opened a shop to sell his paintings and prints, alongside Titus, Rembrandt and Saskia's son. And in that National Gallery portrait, he paints her with a dignity and composure befitting a queen. His queen.

"From that painting, I started researching other love stories. Many have been left out, such as Dalí and Gala's. I tried to include as much variety as possible, both geographically and temporally," admits Trend. Spanish artists are very present in his essay, almost like two sides of the same coin: Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923), faithful and loving husband of Clotilde, whom he married at 25 until death separated them, versus Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), very fond of his many women. "Only Picasso could fill an entire book... He painted all his lovers, but I decided to summarize it with two: Olga Khokhlova and Marie-Thérèse Walter," notes Trend.

Olga was Picasso's first wife, whom he met in 1917 while she was dancing at Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. They soon married and had a son. Picasso continued to paint her intensely and passionately: a beautiful Olga, in the Spanish style, with a Manila shawl and fan he gave her in Barcelona when he introduced her to his parents. But... barely a decade later, he transforms Olga into a monstrous, shapeless, devouring being. With a ruthless and piercing cubism (because it cuts, the painting hurts), the Large Nude in a Red Armchair (1929) is unsettling despite its colorfulness. Especially when, turning the page, another Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (1932) appears, this time sweet, soft, harmonious. It's Marie-Thérèse, his lover for five years, when a 45-year-old Picasso noticed a 17-year-old girl on the street. "It's probably the same red armchair... Seeing those two paintings together is quite visceral. Poor Olga appears completely shattered, and Marie-Thérèse looks beautiful," sighs Trend.

And what about Sorolla? "Affairs generate more ink than happily married couples. The relationship between Sorolla and Clotilde was deep and lasting, he painted her so many times...", now Trend smiles. Clotilde as a powerful dancer, as a saint, as Venus... Earthly and divine, Sorolla's devotion to his wife was total. If The Toilet of Venus (c. 1647-1651) by Velázquez is considered one of the best nudes in Art History, Sorolla's version almost three centuries later is equally remarkable. After traveling to the UK to see Velázquez's painting (then at Rokeby Park mansion; now preserved at the National Gallery), Sorolla also painted Clotilde from behind, but without a mirror and without Cupid. Only she reclining on ethereal pink sheets that enhance the sensuality (and carnality) of her slender body. The painting is simply titled Woman Nude (1902).

ADAM IN THE NUDE (OR NOT SO MUCH)

It wasn't until the 20th century that women painted - and undressed - their lovers. If Botticelli created the first erotic nude since Antiquity, the French Suzanne Valadon(1865-1938) was the first to undress a man in her revolutionary version of Adam and Eve. It was 1909. She is Eve and Adam is the young lover she would eventually marry, André Utter. In this case, it was the woman, a 43-year-old Valadon, who was 20 years older than the man, a friend of her son Maurice Utrillo (conceived with the Spanish painter Miguel Utrillo, although it took him years to acknowledge and give him his surname, but that's another story of the brilliant Valadon, who also captivated Erik Satie).

"Valadon transgressed the rules of Western art, reversed traditional roles in every way. She went from being the model for Renoir, Degas, or Toulouse-Lautrec to becoming a painter," Trend emphasizes. When she exhibited her Adam and Eve at the Paris Salon in 1920, she had to cover Adam-André's genitals with a chaste fig leaf. However, Suzanne's nudity as Eve did not scandalize.

Another artist who reversed roles and tradition was the British Sylvia Sleigh (1916-2010) in The Turkish Bath (1973), the female response to Ingres' classic harem from the late 19th century, with dozens of naked odalisques in provocative poses typical of a male fantasy. "They are undifferentiated houris," criticized Sleigh. Two centuries after Ingres, the artist undressed six of her friends, with recognizable faces, names, and surnames. "I didn't paint them as sexual objects, but as portraits, in a friendly manner and as intelligent and admired individuals," Sleigh claimed. In the foreground, reclining like an odalisque by Ingres, is her husband Lawrence Alloway, painted with the same tenderness, naturalness, and vulnerability as the others.

"Valadon's and Sleigh's works are canonical, the other side of History, in capital letters. Because they show not only a change in art but in society itself," Trend considers.

Another milestone in herself: Tamara de Lempicka (1894-1980), the woman who loved, desired, and undressed other women. Also men. In 1927, strolling through the Bois de Boulogne, Lempicka met La Belle Rafaëla, that's how she titled her voluptuous nude, as elegant and glamorous as it was sexy and suggestive. Lempicka herself explained the encounter with Rafaëla, who was probably one of the prostitutes roaming the park, in the style of Belle de jour: "She is the most beautiful woman I have ever seen. Huge black eyes, sensual and beautiful mouth, beautiful body. I stop her and say, 'Mademoiselle, I am a painter and I would like you to pose for me. Would you?'" She painted her six times in a year. "We know that the last painting Tamara was working on before she died in 1980 was a copy of the painting of Rafaëla from 1927," Trend recounts. More than five decades had passed, but Lempicka still remembered the girl from the park.

SHOOT YOUR EX

The fantastic Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) was one of the most radical artists of the 20th century. Her iconic Portrait of my Lover is more than explicit (1961): a man's shirt attacked with paint and nailed to a slate, with a target as a head. "In reality, I was very angry with my then-boyfriend and enjoyed throwing darts at his image," admitted the artist, who invited viewers to throw darts at that unidentified lover.

De Saint Phalle took catharsis even further in her series of Shooting Paintings, in which she shot paint-filled bags with a rifle to paint/stain/mistreat the canvas. "I shot at dad, at all men, at important men, at fat men, at men, at my brother, at society, at the Church, at the convent school, at my family, at my mother...," De Saint Phalle explained, who in her 1994 memoirs, titled My Secret, confessed to having suffered sexual abuse by her father when she was only 11 years old.

"Love encompasses many different emotions. There is a lot of insecurity, anxiety, rejection, pain... Also a good dose of lust, obviously. But it's not a single emotion, many feelings mix when we are in love," Trend emphasizes. Someone who experienced all the complexity of love was undoubtedly Dora Carrignton (1893-1932). In short: first, she fell in love with a homosexual (Lytton Strachey, from the Bloomsbury circle), then with a transgressive bisexual (Henrietta Bingham) and was rejected by both, but she married a man she didn't love (Ralph Parridge, the object of Strachey's desire: in fact, they lived together for years with her best friend (Gerald Brenan, who had settled in a remote village in the Alpujarras and with whom she had a platonic and epistolary romance). All those loves are reflected in her paintings. Among threatening cliffs, starry nights, and peaceful reading corners, loss, the unattainable, the forbidden... The dark and painful side of love.