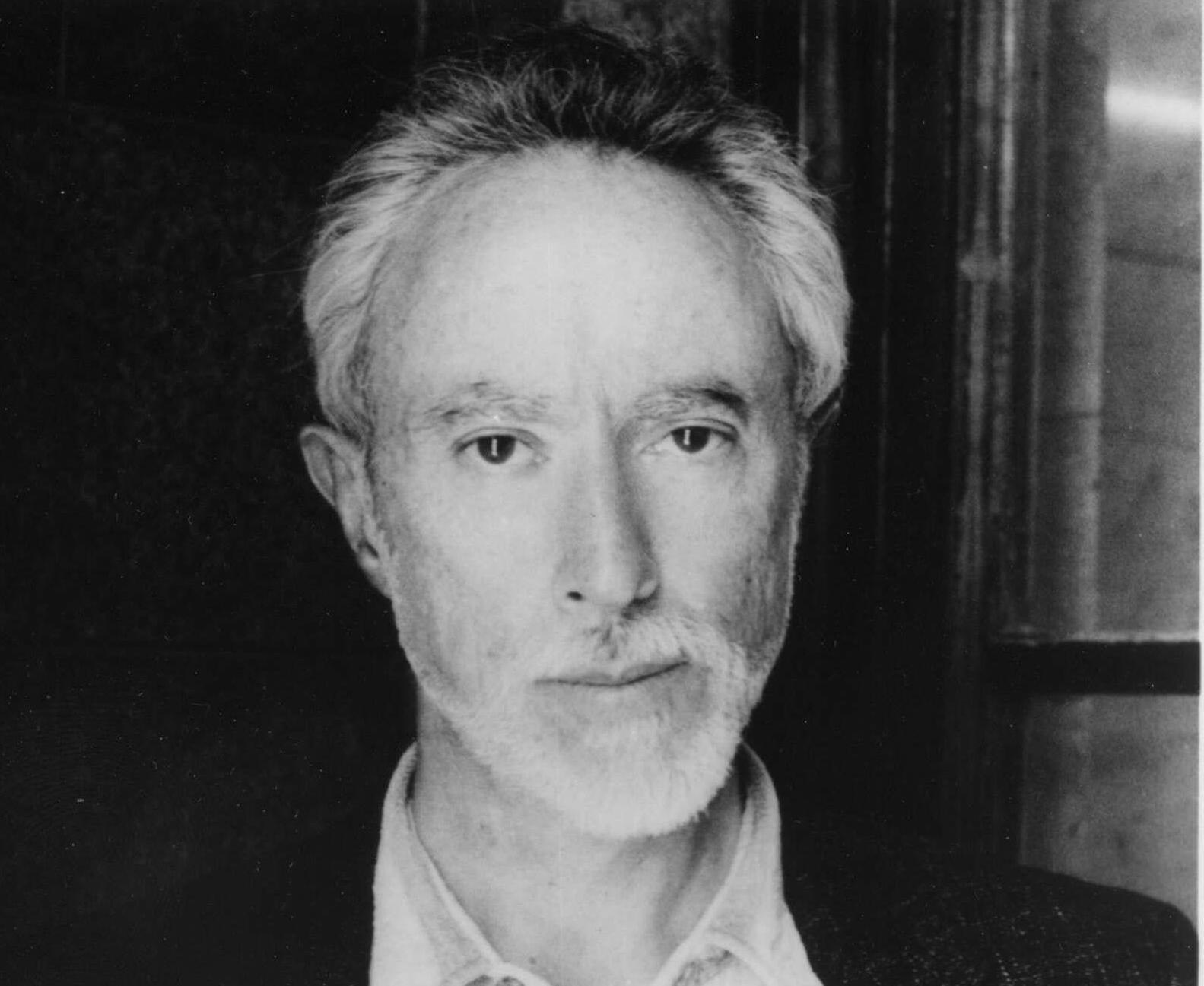

Divorced, father of a daughter, vegetarian, and teetotaler, John Maxwell Coetzee (Cape Town, South Africa, 1940) has been averse to the media long before receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003. Twenty years earlier, he did not attend to collect his first Booker Prize, and it is not uncommon that during his frequent international visits to countries around the world to give lectures or receive honors, he tells journalists, with a polite and somewhat ironic smile, something like: "I do not consider it necessary to make statements". An assertion that complements another of his mantras: "If a book cannot speak for itself, it is a failure, and that author is not conveying anything to the world, has nothing to say, and should remain silent."

When it comes to strictly literary matters, Coetzee, whose books are always uncomfortable, even irritating, seems determined in each novel to write against the reader's conventions, not so much to annoy but to propose new forms. Thus, his novels are perfect Socratic artifacts not suitable for dogmatic seekers of certainties. Pure distilled literature that not even its author, dissatisfied with his achievements, always experimenting, is convinced of fully understanding. A perfect example of this was his latest novel, The Polish Woman, a love story written as a complex literary artifact that seemed more like a composition of notes, ellipses, associations, and white lines that functioned as significant silences.

Another characteristic of this sui generis book arises from the last and striking literary commitment embraced by the author a few years ago, which is both aesthetic and political: adopting Spanish as the language in which his fictions are published, which are subsequently translated into other languages, including English. A fully conscious decision that, as he emphatically stated: "Arises from my distancing from the worldview of English speakers and the danger that the opinions that language holds about the world become global, which is not at all good."

At this point in the story, we must introduce writer and translator Mariana Dimópulos (Buenos Aires, 1973), a resident in Berlin, a specialist in German philosophy, and a translator of Benjamin, Adorno, Heidegger, Musil, and also of Coetzee. It was her task to translate into Spanish a book written in a very special English, designed to be as flexible and unlocatable as possible, and whose original version would be that same in Spanish, not in English. "When it became evident that this would be an unusual type of translation project, our editor, Soledad Costantini [responsible for El Hilo de Ariadna, the publishing house that publishes the Nobel Prize winner in Argentina], suggested that we take notes on our collaboration with a view to publishing something about this process. Those notes became the basis of Gift of Tongues: a book about the craft of translation, about the role of translation in the world, and -to a certain extent- about the nature of language," explains Coetzee.

Indeed, Gift of Tongues is a fascinating exchange of ideas that addresses each of the aspects and great dilemmas of translation, the linguistic experiences of both writers, and also the political, scientific, and ideological aspects of language. As Dimópulos points out: "This is a book about languages, about what languages can and cannot do, and about what we do with languages when we use them and talk about them." And she warns: "It is extremely difficult to adopt a neutral position on the subject. As soon as we stop to think about this ancient and profoundly human tool, we discover that languages can be loved, honored, or treated with distrust -even destroyed-. It is still being debated whether what defines us as humans is the faculty of speech. However, it is evident that languages constitute a large part of what we are."

Q. Now that you mention that, what is the importance of our language in shaping our world? That is, to what extent does the language we speak and its historical, symbolic, etc., baggage determine who we are and how we see everything around us?

JMC. The extent to which the language in which we speak, write, and think influences how we see the world has concerned philosophers for centuries. For monolingual people, the problem is minor. For these people, language is a system of arbitrarily chosen signs that humans use to communicate. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the signs of language and the elements of the real world. Therefore, the world is exactly as it is represented by language. But people accustomed to moving between languages, especially when the languages have no historical connection, tend to be more careful at this point. Why do some aspects of our experience seem to "fit" more easily, be more easily expressible in language A than in language B? It is difficult to scientifically prove that the forms of the language we inhabit predispose us to see the world in a certain way, but I am open to an idea like this.

Q. At the beginning of the book, you establish the crucial difference between "mother tongue" and "father tongue." What implications does the use, especially in creative work, of an acquired language instead of the native one have?

Coetzee knows what he is talking about, as it is a reality he has experienced firsthand, a very representative experience of the 20th-century world in several ways. "On my mother's side, I descend from a Pole who migrated from Europe in the 1880s. Born in Prussian-ruled Silesia, at an early age, it was said that the future would be German.

And so he Germanized: he changed his name, attended a German school, and married a young German woman.

His children were born in the United States and spoke German at home and English in public," recounts the writer. "From the United States, they moved to South Africa, where they continued their bilingual Anglo-German practices, even though at that time they were already living in a Dutch linguistic environment. That is, in the name of social progress, they abandoned a mother tongue -first Polish, then German- for a father tongue -first German and then English-."

On the paternal side, Coetzee continues: "I descend from people who migrated from the Netherlands to the southern tip of Africa in the 17th century. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British occupied that small colony, and its inhabitants became subjects of the British Crown. My ancestors adapted to their new masters: they conducted their public life in English but still spoke Dutch at home -a Dutch that in its most creolized version would be known as Afrikaans-. We find, once again, the story of a mother tongue -Dutch- abandoned for a more powerful father tongue -English-", notes the writer, who also adopted English as a prestigious language and for writing, which logically influenced his work.

"As a child, I discovered, at school, that I was good at English. Apparently, I had a special sensitivity for the language. At seventeen, I enrolled at the University of Cape Town and in English courses, I easily kept up with my Anglo-South African classmates: it seemed I knew the language as well as they did. After graduating, I moved to live and work in London, the heart of the empire. I adapted my colonial way of speaking and my colonial manners. With my white skin, I could soon blend in unnoticed in the crowd," recalls the writer, who would later move to the United States and end up teaching English at the same university. "There was a sort of historical irony in that return: despite not having a drop of English blood in my veins and my firm skepticism towards the ideology of Progress, I was entrusted with conveying the most cherished values of English language and literature to the sons and daughters of British South Africa."

Later, Coetzee continues, "I became a writer, an English writer, in the sense that I wrote in English but treated the language as if it were foreign. I wrote novels that were published in London and New York, the twin centers of English language publication. As I was neither American nor British, my books appeared in catalogs under the catch-all label of World Literature," shares the writer, who over the years began to question his place in that Anglophone world resistant to the foreign -"Foreigners learned to speak English, but English speakers did not need to learn foreign languages"-.

"Then gradually everything changed. I had always felt like a foreigner, an impostor, in the Anglophone culture. And now it was happening that this language, which I spoke and wrote with such skill that I could pass it off as my mother tongue, was starting to feel foreign. Foreign to me, and also foreign to Africa, where I had never put down roots or tried to take root, and where it had never ceased to be the language of the overseas masters. The language of my books began to acquire a more abstract quality. I was no longer interested in sounding like a native English speaker," explains the author about his growing distance from the English language.

An English that, Dimópulos believes, could be losing its global preeminence, as Spanish and French have in the past. "On one hand, it seems unimaginable to think of an end to the current dominance of the English language and the pressure it exerts on the production of knowledge and beauty (literature) in other languages," concedes the writer. "But on the other hand, one can imagine a scenario: that automated translation, once it has migrated enough into our exchanges through the adaptation of artificial intelligence devices, may render translations and knowledge of a common language unnecessary (English). Just activating a tiny automated device will be enough for each person to speak in their own language and be understood by the other in the other's language. The crucial point is which programs will translate these exchanges and by what criteria. But it is very possible that this could be, in the future, the end of English as a global language."

Dimópulos, of Greek and Spanish origin, introduces another ingredient to the debate, the political use of language as a way of uniting and homogenizing a country's population. "In Latin America, it was in the 19th century when nation-states took on the mission of standardizing the central languages and subjugating indigenous populations through language," she explains. "It is only thirty years ago that a series of new regulations in Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina have begun to reflect the multilingual reality of their countries. With the plan for a new constitution, Chile sought to follow a similar path. Let's take the example of Argentina: it is proven that 14 languages are spoken in its territory, but in few bilingual schools, classes are taught in both indigenous languages and Spanish," she denounces.

Q. What advantages does this political concept of "one state, one language" entail, and what are its dangers?

That a community forms its identity largely through a common language is an experience long predating this form of government, but nation-states have tended to unify their inhabitants under the idea of a people, that is, a unified cultural and linguistic tradition, and to systematically exclude or marginalize those who do not belong to the official language and culture. It may seem difficult to think, but this has by no means always been the case. And this aspect of systematic marginalization and exclusion still exists in many societies, if not all. Something particularly interesting is what happens between the familiar and the foreign in the sphere of literary writing and translation. Because this complex relationship also reflects how we constitute ourselves as subjects and as writers. That's why we included that epigraph from the German poet Hölderlin at the beginning of the book. The experience of other languages, the act of coming into contact with other cultures, helps us understand our own in a different way. Our identity is always influenced by the experience of what is not ours, but especially when there are changes in language or migration in our personal history. This experience, for me, is one that demands from us but enriches us, I would say in almost all cases.

They warn about the risks of equating identity and language. How is this tension resolved in a world where identities are increasingly important and where at the same time diversity is sought to be preserved?

Individual identity, but above all collective identity, is often articulated through linguistic identity. World regions are identifiable -and identify themselves with pleasure- by the language they speak, or the dialectal variety used within a larger language, or the idioms cultivated by a sector of a community. There is nothing inherently wrong with this. We all speak with an accent, it's just that what we first hear is the other's accent... while the other first hears ours. In this sense, identifying oneself through a language -saying I am or we are this language and we are proud of it- seems better to me than identifying and, above all, reducing someone, an other, to the language they speak. Because this is the seed of discrimination. And I think that remembering that we all speak with an accent is a good remedy against the sometimes automatic act of segregation based on linguistic variety or language difference.

Beyond whatever motivations there may be, is it possible to modify a language, that living and changing entity, from a political standpoint, through an imposition of specific rules?

Yes, it is possible to modify a language from above. This is a matter that has been debated since antiquity, about what it means for languages to be by convention. The argument back then was that if languages were so by convention, then someone could decide, for example, that papirla means "a tree that bends with the wind" and use that nonexistent term with that meaning just because they decided so. That is, modifying a living language. Of course, this is nonsense. But since nation-states took on the unification of national languages and widespread literacy, there have been clear cases of language modification. One of the most evident modern examples is the Turkish language: in the twenties and thirties of the last century, Atatürk and his government imposed a new alphabet and introduced many modifications to the Turkish language that still stand today.

There is much debate about the ethical limits when translating a text into another language. Is it advisable to rewrite, modify, or qualify a text, especially a non-contemporary one, when it uses offensive terms of any kind, or should the author's will, even if mistaken or anachronistic, prevail?

This has become an important issue in today's literary market. And it affects not only translation but also the republication of certain classic texts that may offend modern sensibilities in their treatment of race or gender. At the simplest level, the problem is terminological: certain derogatory racial terms used in the past have become unacceptable in the modern world. Similarly, linguistic constructions that once seemed perfectly natural -such as, for example, using the male pronoun to refer to people in general- have an inherent bias that may not have been questioned before but is now unacceptable. My tendency is to act pragmatically. In books, including translated books, that have the status of classics, that is, that are studied in schools and universities, I believe it is important to stay close to the original, to the author's words.