Even today, 80 years after Hitler's suicide, the question that haunted the world that summer of 1945 is still asked: How was it possible for one of the most cultured and advanced nations in the world to fall into the utmost barbarity? However, the question assumes that Nazism was a sudden evil that sprouted rapidly and spread without the diseased body having time to react. For the German-Jewish philosopher Victor Klemperer, the question was different, as he posed in his book 'LTI. The Language of the Third Reich: Notes of a Philologist': "How was it possible to spread this book in the public opinion and how, despite this, the reign of Adolf Hitler was possible, since the bible of National Socialism was already in circulation several years before taking power: this will always be the greatest mystery of the Third Reich for me."

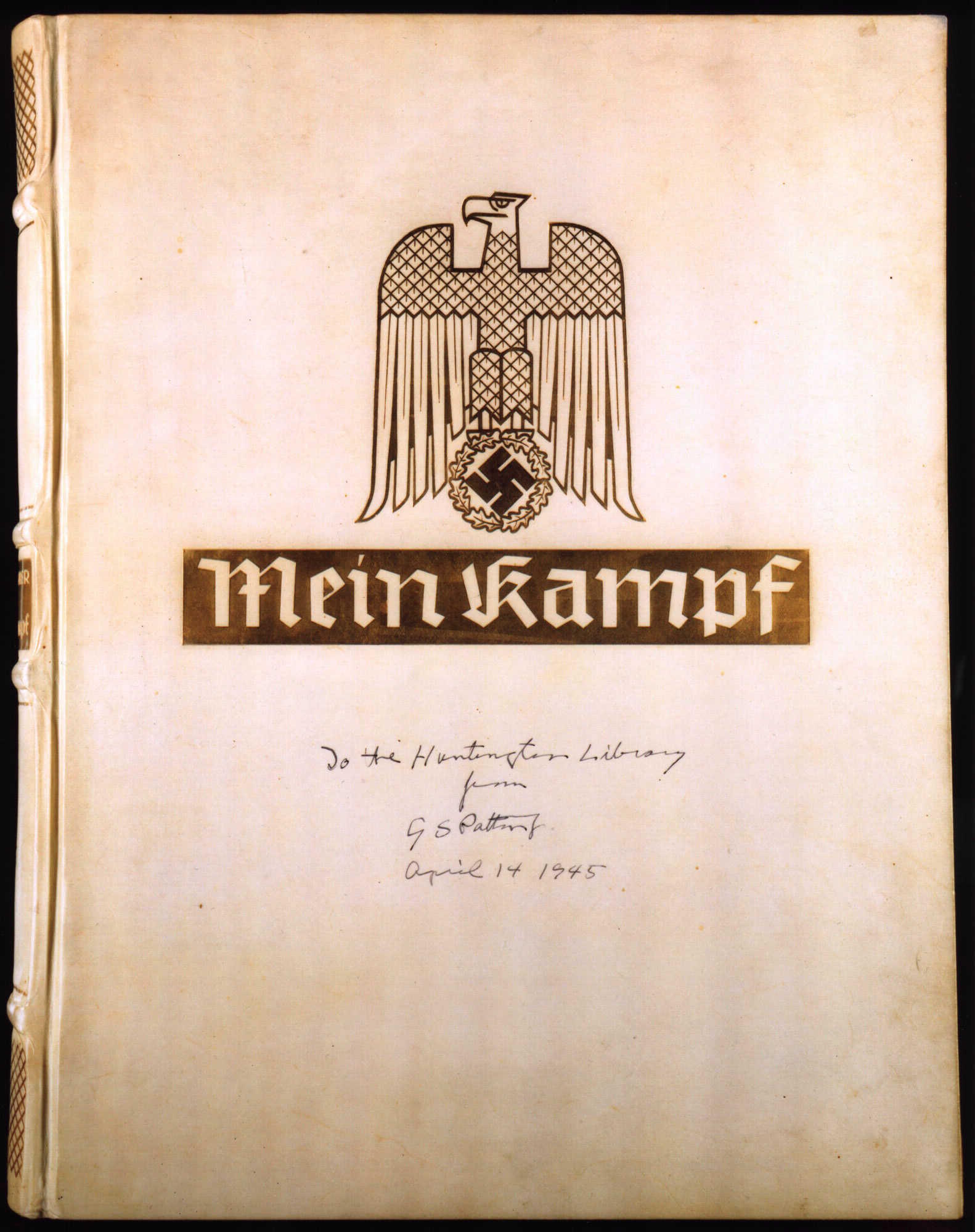

Klemperer talks about 'Mein Kampf', the book in which Hitler clearly outlined his program of crimes and whose first part reached German bookstores on this day, 100 years ago on July 18th. The volume had a lukewarm reception initially, but after Hitler came to power in 1933, it became the ideological culmination of Nazism. It was given as a gift to newlyweds in Germany, and it is estimated that by the end of World War II, there were 12 million copies in households across the country. This is in addition to the multiple editions in other languages, including one in braille.

'Mein Kampf', one of the most problematic titles in the history of literature, was crucial for Hitler's development. So much so that, starting in 1925, in the tax notifications of the German administration, the Nazi party leader declared his profession as "writer." All thanks to a text he crafted while in prison (under extraordinarily comfortable conditions for an inmate) at Landsberg Prison. He ended up there after the failed Munich Putsch of 1923, a failed coup d'état organized by the Nazis in the Bavarian capital in 1923, inspired by Mussolini's march on Rome. Quickly suppressed, Hitler was arrested and sentenced, along with other Nazi leaders, to five years in prison, of which he served only nine months. At Landsberg, he received numerous visits from his collaborators, but then he asked for them to stop to focus on writing a book. This book was initially titled 'Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice', and was partly dictated to his fellow Nazis in prison, Emil Maurice and Rudolf Hess. Upon his release, the publisher Max Amann convinced him to change the title to the much more concise 'Mein Kampf'.

"The book is unreadable: very long, repetitive, disorganized, poorly written... It can be summarized in 30 pages"

"The book is unreadable," states José Lázaro, professor of Medical Humanities in the Psychiatry Department at the Autonomous University of Madrid and author of 'Hitler's Success. The Seduction of the Masses' (Triacastela), published today to coincide with the centenary. "It is very long, repetitive, disorganized, poorly written... Practically no one has read it in its entirety, and it is not necessary, because everything the book repeats over and over can be summarized in 30 pages."

Basically, the struggle mentioned in the title is that of a frustrated Austrian painter who, after being rejected from art school, led a wandering life in Vienna and eventually settled in Munich. When World War I broke out in 1914, he was called up by the Austro-Hungarian army but was declared unfit for service. He then volunteered for the Bavarian military and went to the French front. He was awarded the Iron Cross for his performance in battle and would recall those army years as the happiest of his life.

However, the armistice, demobilization, and the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the German Empire and imposed onerous territorial and economic losses on the country, left a deep mark on young Hitler. It is in this context that the deep resentment underlying 'Mein Kampf' began to brew. It is a diatribe against liberal democracy, which ended a war mired in trenches, but also against capitalism, for its stock market and speculative manipulations that alienated the population from their daily reality. And above all, the focus of 'Mein Kampf' points to the Jews as conspirators, a shadow power manipulating the world's strings and responsible for all of humanity's problems. "Today, it is difficult for me, if not impossible, to say when the word 'Jew' first made me think in a special way," Hitler admits in one passage. "For me, it was during the time of the greatest spiritual upheaval I had to go through. I stopped being a weak cosmopolitan and became an anti-Semite."

This anti-capitalist discourse links 'Mein Kampf' to many political movements today, some seemingly ideologically opposed. But there is another element that is common in our days, as pointed out by Alejandro Baer, author of the recent 'Antisemitism. The Eternal Return of the Jewish Question' (Catarata). "In reality, Hitler is not very original. What he writes is a kind of pastiche, a recycling of racial and conspiratorial theories that have circulated since the 19th century, like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," says Baer. "In fact, the conspiracy theory is a structural element of anti-Semitism. It is what distinguishes it from other forms of racism, where a racial characteristic of inferiority is always attributed with negative elements of all kinds. For example, in the colonized subject, it is claimed that they are savages, dirty, thieves."

Baer points out that Jews were also attributed with all these characteristics. "But the central aspect of anti-Semitism, and what connects it with all conspiracy theories, is the attribution of malice and, above all, power," he notes. "Power in the media, in finance, in culture, but also the corrosive effect of Jews on national cultures and equally attributing to them all the major transformations of the 19th century: secularization, urbanization, socialism..."

Another key element that Hitler embraced, according to Baer, is the racial theories of the late 19th century, as he was very familiar with the anti-Semitic literature of his time in Austria. "What these theories were saying was not just a prejudice against Jews as scapegoats, but a worldview that understood Jews as an existential threat to an imagined Aryan race or the German nation." In other words: "It's either them or us." A reflection that "today seems like delirium," but points to a common element in all historical forms of anti-Semitism: "Seeing the Jew as opposed to national order, religious order, racial order."

The Nazis spoke of the 'Gegenrasse', the counter-race. "Ultimately, it reproduces a scheme that we could almost say comes from theological anti-Judaism," says Alejandro Baer. "Before it was the Christian people, and now it is the 'Volksgemeinschaft', the national community, defined in opposition to the Jews."

José Lázaro adds another perspective to the analysis, within one of his research lines: "Pride and desire, understood in a very broad sense, play a fundamental role in human behavior. Pride as everything that gratifies the self, reinforces us, and desire as everything that gives us pleasure, that instinctively or impulsively we tend to achieve. In that sense, 'Mein Kampf' is a paradigmatic example of how a human being is capable, after having suffered a series of humiliations and frustrations throughout their life, to surprisingly effectively connect them with the frustrations and humiliations of their people and make an explosive cocktail out of it."

In other words, turning it into a message of the type: "We are a superior people, our inferior neighbors have humiliated us, the Treaty of Versailles has exploited us, they are robbing us, and we will not allow this to continue, we will stand up and reclaim what is ours." Lázaro reflects: "Ultimately, my suspicion is that this discourse, more or less softened, is what all leaders with authoritarian tendencies repeat. If there are two things that convince everyone, it is to be told that they are wonderful and that they are being mistreated, and therefore they must revolt against those who humiliate and rob them."

Thus, the author of 'Hitler's Success' points out that democracy is somewhat unnatural, as it does not seek the immediate satisfaction of the most primal principles of human beings. Similarly, this combination of pride and desire is evident in current leaders. "We see it in narcissistic figures with authoritarian tendencies, like Trump," he adds.

The great paradox, according to the scholars of the book, is the importance Adolf Hitler placed on written format, despite his strength being in oratory. "He himself was aware that he wrote very poorly and that all his strength lay in his oratory. To a large extent learned and rehearsed by a very curious author of the time, Gustave Le Bon, who wrote a book, 'The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind,' which today no one reads and is also very poorly regarded, but which decisively influenced him, as well as Lenin and Churchill," Lázaro points out. "All populists in some way use a certain victimhood and refer to those two basic forces of every human being, which are the sense of self - call it pride or arrogance or narcissism or whatever we want to call it - and then desire. The frustrations of desire and the wounds of pride are what produce resentment, almost by definition."

"As a propaganda tool, it is not the only one, but it was very important that it circulated massively," Baer points out about 'Mein Kampf.' "Furthermore, a book always carries an element of authority. 'The Protocols...' were believed as a document," he explains about the libel whose falsehoods form the basis of much contemporary antisemitism, including 'Mein Kampf' itself.

What remains of these pages in our days? In 'Mein Kampf: The Story of a Book' (Anagrama), the French journalist Antoine Vitkine analyzes the great appeal that the volume continues to have, especially in Muslim countries. And he cites a case: "Manifesto, a small Turkish publishing house, publishes a new translation of 'Mein Kampf' in 2005, which is sold at a lower than ordinary price, equivalent to three euros, with an attractive color cover, similar to a movie poster. In the immediate aftermath, the commercial success of this low-priced version is exceptional. A few weeks later, two other publishers, upon seeing the good fortune of their colleague, also publish two new editions of 'Mein Kampf,' also in cheap editions. A few months later, the result shows sales of 80,000 copies."

According to Baer, this phenomenon is part of other more complex currents. "His criticism of capitalism revolved around a false dichotomy between the sphere of production and that of capital," he states. "The hated capitalism was not that of productive work and industry, but that of parasites - money and finance, speculators and bankers. Ultimately, as the ideologues of National Socialism repeated, it was a Jewish capitalism."

Against the real, productive, and concrete world of the 'Volksgemeinschaft' (the national working community, rooted in the soil and blood) were "the deceitful, speculative, and vampiric forces of the abstract: the mobile, intangible, and international Jew." In other words, "it is not so much capitalism itself but Jewish capitalism. To attribute to the Jewish what is false, mean, merely instrumental." And that brings us to today: "While racial theories have no force today, this notion of Jewish capitalism remains widespread. Along with conspiracy theories, that mental structure of thinking that all reality and all social and political problems are attributed to a single cause, invisible forces. We can call them 'international Jewry' or we can also call them 'globalist elites,' as populist right-wing does. There is still a structural antisemitism, sometimes without mentioning Jews, but directly inherited from 'Mein Kampf'."