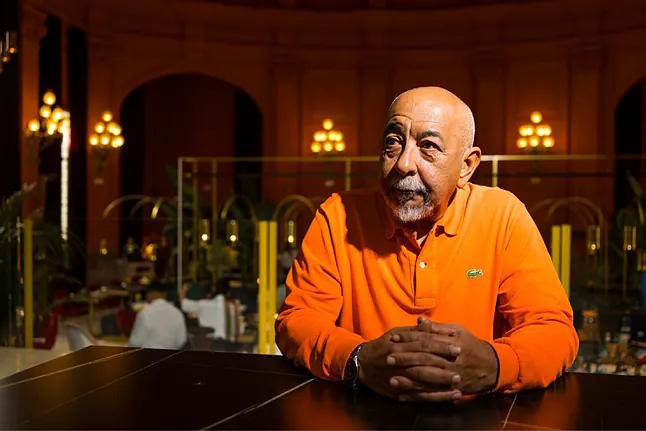

In all human cultures, since ancient times, parricide is one of the most abhorrent crimes a person can commit. Not in vain, since ancient Greek times, it has been used as a dramatic resource and as a representation of social rebellion and moral degradation that exceeds all established social codes. Precisely, a parricide is the catalyst that articulates the plot of Morir en la arena (Tusquets), the new novel by Leonardo Padura (Havana, 1955) who, as always, skillfully weaves this drama within the broader drama of a Cuban reality that he judges to be "in a constant state of degradation."

Based on a real event from a close family, but conveniently altered, the writer confesses that it is always difficult for him to determine exactly where the ideas to write a novel come from. "I am not a writer with a folder of ideas, but I draw from reality, from memory, and this phenomenon of parricide suddenly illuminated me for something I wanted to try writing, a kind of summary of what has been the life of a generation, the outcome of a generation's life, of my generation in Cuba, in the current terrible situation," explains Padura. "So, based on this event, I build a whole dramatic tension to support those conflicts of the daily lives of these characters with a much broader projection."

Furthermore, the writer elaborates, "parricide always has a psychologically strong connotation because in general, we all commit parricide. Writers, for example, often commit parricide with authors of the previous generation. Killing the father is almost a necessity for reaffirmation," he argues. "Now, when parricide becomes a physical act, a real crime, it has other much more complicated connotations."

In the case of Morir en la arena, the return home of the killer Eugenio Bermúdez after 30 years in prison disrupts the life of his brother Rodolfo, a timid and newly retired man marked by a traumatic experience in the Angolan war, and his wife Nora, who have secretly loved each other for over half their lives. Redemption and forgiveness are the major themes that hover over this book, as well as melancholy for a lost past and a future that never seems to fully materialize. A kind of generational chronicle about the bitterness and defeats of those who are nearing 70 years old.

"It's not that I have become more melancholic now in old age, seriously - he points out with a laugh - it's that Cuban reality has become more bitter and harsh with each passing year. Since the fall of international communism in the 90s, Cuba faced a crisis, but we have been in a crisis for over 30 years now, and the consequences are becoming increasingly severe," justifies Padura, who in the novel describes how Rodolfo and Nora manage to survive thanks to the donations sent to each of them by their emigrated daughters, one to the United States and the other to Spain. "Years ago, a retiree could guarantee their survival with a pension, even if it was small, but today that is impossible," he states emphatically.

"In Cuba, keeping silent is already a national custom. As the saying goes: If it's hard to eat on the street, imagine in jail."

"Ironically, last month pensions were increased, but the average still does not reach $10 per month. Until recently, the pension my mother received, for example, was 1,520 pesos in a country where a pack of 30 eggs costs 3,000. So, how can a retiree earning 2,500 pesos live in a country where you can't even afford to eat a daily egg?," Padura wonders.

This simple fact illustrates the deterioration of a society that the writer portrays with pain and mastery, which, as he says, does not only affect the economic or social aspects. "The general degradation has also affected artistic creation. I just read this morning while having breakfast that right now the 10 most listened-to songs in Cuba are reggaeton. How is it possible that in a country where, as is known, music has always been the most important, richest, and best-known cultural manifestation, we have reached these extremes of vulgarity?," he laments.

Just as he reflects on the evolution of a society marked by poverty, silence, and exile, very much in line with his recent memoirs Ir a La Habana, Padura also reflects in this novel on the summary of what has been an entire literary generation through the character who narrates a good part of the book, the writer Raymundo Fumero, a relatively successful author in the context of Cuban literature from the late 70s, the 80s, until the early 90s. "In the 70s, a series of conditions and demands were established towards art, which began mainly with the marginalization of many intellectuals, writers, artists, and educators, the so-called parametrization: those who did not meet certain parameters could not be representative of Cuban culture or education."

It was the case, he recounts, for authors like Virgilio Piñera, the great Cuban playwright of the 20th century, or the great José Lezama Lima. "Both died in total ostracism at the end of the 70s, they were never mentioned again, nothing was published, nothing was said. I remember reading the death notice of Lezama in the Cuban newspaper, and it was a six-line note. A giant of Cuban literature practically ignored by the media and the country's reality," recalls the writer. "In summary, what that experience of those years meant, having to adapt any expressive need, any possibility of writing to very closed and ideological codes, marked the destiny of a generation, made them create from fear, something that was common to the whole society."

And fear is the other major theme of Morir en la arena. Fear of death, truth, freedom, and a hard and sad life, but also fear of denunciations, power's reprisals, even of thinking outside the box. "Fear is a natural human reaction. Speaking of writers, if you know that what you write will not only not be published but that censorship can bring other additional punishments. What do you do then? You start looking for survival strategies, whose first step is self-censorship, and that mental climate has marked the development of Cuban culture and specifically Cuban literature until today."

"In Cuba, the homeland of music, now only reggaeton is heard, social deterioration has led to cultural deterioration."

But not only in literature or the arts, but also in the rest of society, which refers to power as "those at the top" and the impoverishment situation of the island as "the thing". "People in Cuba have to stay quiet, it's already a kind of national custom. But it's not because they want to, of course, but because they know the consequences that can come from speaking out. It happened with the protests that took place three or four years ago, where people took to the streets and a young man who broke a window was sent to jail for 10 years," exemplifies the writer, who adds a very graphic saying that has become popular in the country, where people say: "If food is so hard to find on the streets, imagine how it must be in jail".

Jokes aside, the writer sadly acknowledges that, like almost all his compatriots, he is unable to see the light at the end of the tunnel. "So many years of experience have shown us that the regime can endure indefinitely. It has no expiration date, although the exhaustion and weariness of the people is increasing," recognizes Padura, who as is known, continues to live in Havana, in the same house where he was born, located in the popular neighborhood of Mantilla. "I have fewer and fewer friends in the neighborhood, some because they went into exile, others because they moved away, others because they have passed away. Because, well, we are getting on in years. But with those who are still there, I see this tremendous situation reaching its limits, and not being able to do anything, just seeking survival strategies," he insists.

Living despite everything

Precisely emigration, which 10% of the island's population has practiced in the last five years, as he alarmingly comments, has recently changed due to the restrictive policies of U.S. President Donald Trump, something that, according to the author, is another nail in the Cuban coffin. "Before, it was the main destination, because there was the benefit of being able to avail oneself of the Adjustment Law, which allowed Cubans arriving in the United States to quickly obtain residency and economic assistance, but that path has been closed," he explains.

"Now a very current topic of conversation in Cuba is whether you have a Spanish grandparent", Padura says ironically. "Everyone rushes to unearth their relatives' bones, because they say that the deadline to obtain Spanish citizenship through the Historical Memory Law expires in October. Many have succeeded, but it is very painful to see how a project that was born to create collective well-being has ended up being every man for himself, because only individually can people solve their major existential problems, ranging from feeding themselves to having the possibility of a more dignified life."

However, as he always does, the writer does not succumb to defeat, and if in this novel the mature love of its protagonists is the escape valve from those thwarted lives, he assures that despite the blackouts and shortages, people resist. "It's wonderful to see how in the midst of this catastrophic and dramatic situation, people live. People dance and listen to music, when they have rum, they drink rum, when they get a chicken, they eat a chicken, and if they don't have chicken, they eat a corn cob or whatever. And people connect and fall in love, and sometimes even have dreams, ranging from fleeing the country to hoping the electricity doesn't go out that night," he ironically points out again.

"You Spaniards know this from the memory of your grandparents. You know that under very terrible conditions, people sang sevillanas, went to see the bulls, or went to watch Di Stefano play soccer, at a time when everything was messed up in Spain," Padura recalls. "Here it's the same now, and seeing all that makes me feel a closeness to that resilience that people have, with their resilience, a word I hate but unfortunately is very trendy. This is what drives me to write, to bear witness to this very tough era," he concludes.