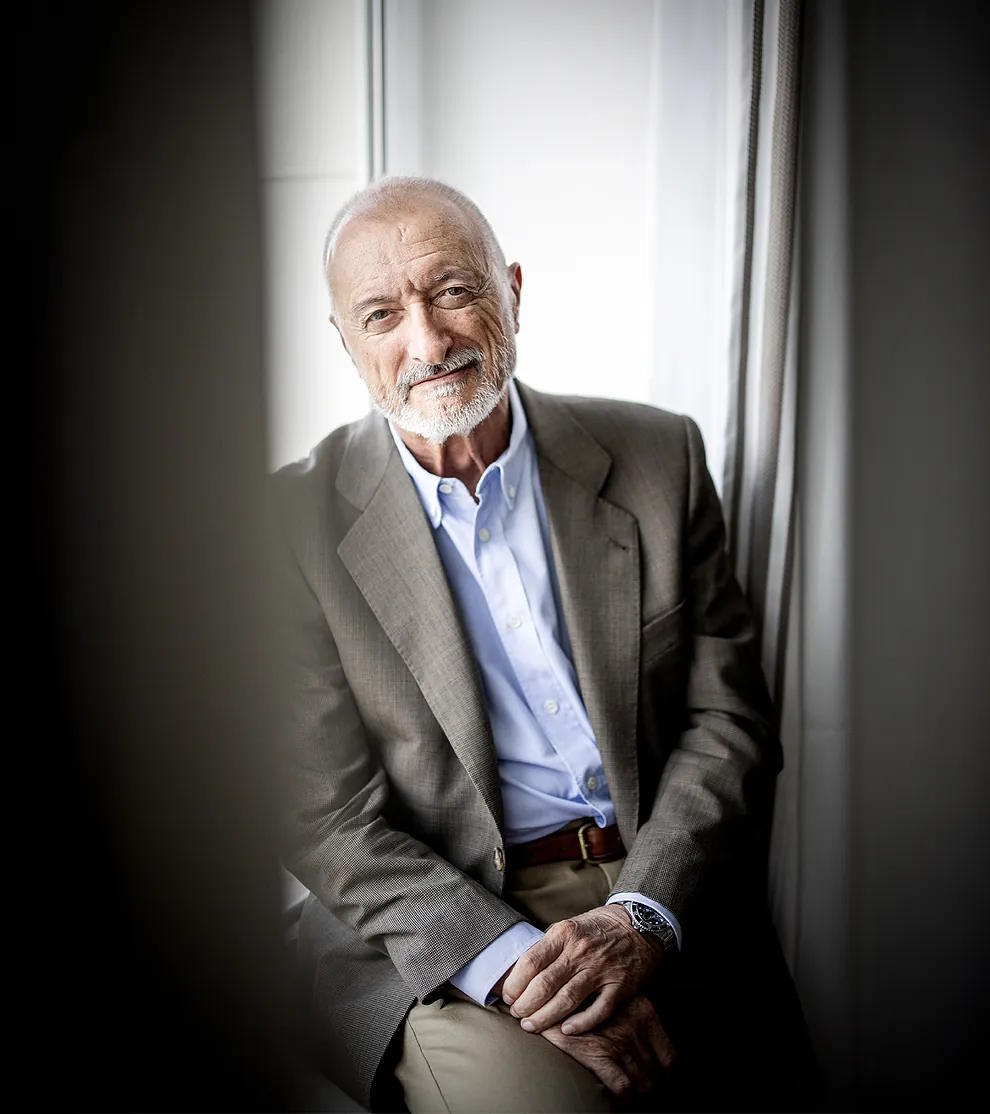

At a bullfighting hour, Arturo Pérez-Reverte (Cartagena, 1951) receives at the Hotel Palace in Madrid, like a bullfighter before entering the arena. A celebrated novelist, a vocational reporter, an incendiary columnist. He arrives for the interview after presenting Mission in Paris (Alfaguara), the eighth installment - available since yesterday - of the popular saga featuring Captain Diego Alatriste. The swordsman of the Flanders Tercios returns 14 years later to take us to La Rochela and the Huguenots' rebellion against King Louis XIII of France. The novel appears on the eve of the 30th anniversary of his first Alatriste. Pérez-Reverte himself reveals that he has another one ready, which would be the last in the series. Mission in Paris will stand as one of his great works, which is saying a lot for an author with over 27 million books sold worldwide and who masters the genre of pure fiction like few others, that is, the one that aims to entertain, amuse, and educate.

Why return now with 'Alatriste'?

Because during this time, there were other things I wanted to do. I am happy with the character. I didn't hate him, like Conan Doyle hated Sherlock Holmes. To me, he is like a dear friend, although there were other novels I wanted to write. I don't know how much life I have left, but I planned to write the novels I had in mind, which had nothing to do with this saga. And now I return, as it is about to be 30 years since the publication of the first Alatriste. Readers ask for it. Some people have even gotten angry with me, people who have 'Alatriste' tattooed on their arm or leg. If I live long enough and feel like it, there will be another Alatriste. And then I will stop.

How has the character changed?

The trick is that he hasn't changed; I have changed. In fiction, a year has passed, but in my life, 14 years have gone by. And I am not the same. The fear I had was reaching sadness. That, being so different now, I couldn't recover it in the same tone and with the same truth. Alatriste now appears more bitter, has more regrets, is darker. But it works for me because I am also like that. My life experience in these 14 years has helped shape the character, but it was hard. It was very hard. Even in the language, to make it elaborate and classic yet understandable to a modern audience. That is not improvised. It has been a very enjoyable job. I am happy with the result.

Alatriste remains a hero dedicated to concepts like homeland, God, flag. Is he a moral hero?

Alatriste has been a soldier, and the grand words no longer serve him. He needs something to lean on, a moral, ethical, personal support. He will die for a king he has seen is corrupt. So he creates his own rules: loyalty, camaraderie, courage, dignity, honor. He is not a moral hero. He is a guy who has killed for money. But his moral reserve is above the world he lives in. My heroes are never pure. Sometimes they are villains.

You mentioned that 'Alatriste' is now more bitter but also more human. Just look at the Borgoña he takes on.

Because I am also more human than two decades ago. Old age gives you a different, deeper, and more lucid view of things. But at the same time, more compassionate. There are things that now move me that didn't move me before. I used to be a tough guy. Now I see the world in a more compassionate way. A word that in the world I come from, that of war correspondents, was not common. It was a harsh world, like Fernando Múgica's or Julio Fuentes'. Age has made me more compassionate. And it allows you to take a step back from things. By not being involved, you see everything with more serenity. One can be supportive of seals, Palestinians, or Eskimos. There is passion there, not reason. But age, by giving you that serene coldness, allows you to be compassionately rational, that is, with arguments.

Does 'Alatriste's bitterness translate into a bitter chronicle of Spain?

Being Spanish and lucid, it is impossible not to be bitter. To understand this, unless you are foolish, just read a sonnet by Quevedo. You have to see Spain as it was in those grandiose times. The Empire did marvelous things. There are Lope, Cervantes, Velázquez, Quevedo himself. Spain was something that not even the USA is today. Everyone spoke Spanish. Spanish theater influenced the world. All of that is great. But there is also a dark, murky, dirty, cruel Spain. Let's face it, there is a very important point for me: epic is frowned upon, it has a bad reputation because it was abused. Both Francoism and the other -isms. It was so overused that people acquired a healthy caution towards epic. But epic is necessary and, moreover, it is good if it is rational. With Alatriste and other historical novels, I wanted to give back to the Spanish reader an epic in a clean way. It is an epic not tainted by one Spain or another, not left-wing or right-wing. In the Battle of the Ebro [during the Civil War], as epic was the 18-year-old from the PCE fighting as the Falangist or Requeté youth. And I say this, knowing that my father and uncle fought in the war with the Republicans. There are admirable things in our history. How can you not admire Daoiz and Velarde in Monteleón Park? How can you not admire a Spanish Tercio that does not surrender to the French? How can you not look at the guy crossing the Ebro at 18? If Franco abused the epic, it is Franco's fault, not that of that Tercio. In my modest role, with these novels, I try to give the reader an epic that has no ideology, that is human. It's not a debated theory. I have been with people who could be wonderful or pure bastards on the same day. Alatriste is born from all of that.

Does this renunciation of epic also explain why Spain lacks a cohesive narrative?

The problem in Spain is not political or social, it is psychological. We are messed up. We have been messed up, left with a series of complexes and manipulations in our heads like no other country in Europe.

Who messed us up?

Those who have always been in charge of the mess. And I'm not just talking about Franco. I'm talking about the 19th century, about Fernando VII, about the Inquisition, about the fight against the Moors. Eight centuries of civil war with the Moors. And then the French. And the Moriscos, the Jews, the liberals, the Carlists... Reading provides defense mechanisms, but not receiving, or not wanting to receive, a good education leaves you defenseless. And that is the problem in Spain. There is a left that ridicules a noble epic and a right that appropriates and distorts an epic that does not belong to them. Or are all heroes right-wing and all revolutionaries left-wing? This huge confusion is cured by reading, and I have done my small part. Others, greater ones like Galdós or Baroja, did their part in their time. I have a clear conscience.

You have always said that you created the 'Alatriste' saga to reflect the Golden Age due to the dismantling of History and Literature in educational curricula.

Yes, it was born from my daughter, who was 12 at the time [in 1996]. I asked her to lend me her textbook, and the Golden Age, when Spaniards were great, was reduced to four lines. Don Quixote is the most read book in human history. People wanted to speak Spanish because it was a trendy language, like English is now. We had the world by the balls. We had America. In 1650, there were 50 universities, 20 of which were in America. And all of that in textbooks is reduced to an Inquisition bonfire, an expelled Jew, and something about Franco, I don't know what. Go to hell. That is Spain's problem, and that is why history now becomes a political weapon. Those who arrive late miss out. Franco's era ends, democracy arrives, and it took years for the rulers to say the word Spain. They were ashamed because Franco had abused it. What happened? The right came and said it's mine. Instead of saying let's clean up the word Spain in schools, let the kids see that Spain is something else, the Spain you want to vote for, plurinational or whatever... Well, no. And that is very Spanish: what you don't understand or don't care about, you push aside even if it is valuable. That is our great sin here: we are in chaos with different interpretations. I was born in 1951. We grew up against the system, which was then Francoist. Now young people are against something, but it's something else. In Spain, the young are always against something, and they always vote against something. They don't vote for Sánchez or Feijóo; they vote against the other. Spain is a very dangerous country. You have to be very careful, very cultured, very tactful, and very decent to handle it. And that is what we don't have in Spain, neither on one side nor the other.

Have we gotten worse in these 14 years?

Worse, especially in terms of humanity. After the Transition, Spain became an example. It was an admirable country. We did something extraordinary. There was ETA, the military, all of that. To deal with it and get individuals like Carrillo, Fraga, Arzalluz, or Pujol to sit down and agree. Many things may have been done wrong, like education.

Is education management the main hindrance over the last decades?

It is not the main failure, it is the failure. The biggest mistake of the Transition was allowing education to be divided into 17 different parts and left in the hands of local and peripheral interests. That brought incompetence. Now they say: I dance the sardana or play the Gomeran whistle. Go to hell. Tell the kids about the Carlist Wars or the War of Succession in Catalonia. But this is not done because it is not of interest. Go to a village in the Basque or Catalan countryside. The word Spain does not exist. And I don't say this as a lament, because it is what we have been doing. A country as complex as this one, historically so complicated, so ethnically and linguistically diverse, needed the goodwill of a mortar that would keep the parts together. That does not exist. The Monarchy, which is respected, the Civil Guard, and soccer are the only things that unite the Spaniards. The rest have made us despise it.

What literary sources do you draw from?

I write with what I imagine, with what I have lived, and with what I read. In the library of my house, I have no phone or internet. I have an isolated computer and 35,000 books. That's where I draw from. And then life, of course. When I talk about violence, pain, loneliness, it is not imagination; I have seen it with my own eyes. I have seen a woman with her face cut. I know what it is to vomit out of fear. I know what it is to drive down the road after losing everything, in Bosnia or Sarajevo. Here we are not used to it. We have lost the habit of pain and horror, we have believed that we were safe from everything. Then comes the pandemic, the dana, the fires, or whatever.

In Europe, we are the garden of the world, as Josep Borrell often says.

Europe no longer protects anyone. It is a farce, a theme park for selfie tourists where not even the Europeans themselves know their own history. I was born in a Europe where there were Pius XII, Churchill, Adenauer, De Gaulle, communists like Berlinguer, or socialists like Olof Palme, or people like Eisenhower or Kennedy in the US. That was the intellectual level. Now they are all dwarfs. It's between kissing up to Trump and fearing Putin. Europe is dead, although empires take a long time to disappear.

In a meeting at the Ateneo de Madrid with Antonio Lucas, almost a year ago, you stated: "The most a human being can aspire to is to understand." What things do you not understand?

I didn't remember, but it's true. I have the age, the readings, the life experience. And I look, I have eyes, I observe the world. Every day I read four newspapers: EL MUNDO, Abc, La Razón, and El País. And I see what I can and listen to the radio. And of course, damn it, I lead a very eventful life and have paid very high prices for it. But I understand the world. That's why I write novels. And I don't have the right to tell young people that the world is crap. They have the right to believe, to fight, to make mistakes, to shake up the world. It moves me to see young people when they get angry and fight. I really like it.

However, they are often labeled as complacent or bourgeois.

That's because European society, not just Spanish, has committed the huge sin of making them forget that the world is a dangerous and hostile place. Look at the young people in Ukraine fighting on the front lines.

Would we have a similar reaction in Spain if we were faced with a similar war conflict?

Yes. Not to go defend Ceuta and Melilla, no. They would tell you 'go to hell'. But in the face of a foreign invasion, I am sure that the reaction of young people would be similar. Look at what happened during the dana. Who were the first to grab shovels? Taking up arms is more extreme. But if life takes you far, you grab it.

Is politics in Spain a mirror of society or a grotesque distortion?

I am not a political scientist. Spain has flaws and virtues. Spanish politics stem from our flaws. Politicians have shaped a society to fit them. That is, they have taken our measure. And they take advantage. Politicians have shaped a Spain useful for their business: polarization, corruption, demagogy, catchy slogans. They have exploited our weaknesses. Above all, our lack of education.Can a link be established between the corruption in the world of 'Alatriste' and the present?

Yes, and not only in our country. In Spain, what the king did was sell postal positions. A corrupt bureaucracy was generated that we have maintained until now, and that has persisted in South America. When you read a sonnet by Quevedo, it seems like he is talking about the Minister of Transport.

Has the political evolution in Latin America fueled the black legend?

The problem is that Spain has ideologically and morally abandoned America. Out of complexes and incompetence, Spain has not known how to deal with indigenous or pseudo-indigenous movements, because López Obrador and all these people are not indigenous, they are a bunch of corrupt opportunists who use that to continue as usual. Spain should have a Ministry of American Affairs.

You mentioned your experience as a reporter earlier. What is happening in Gaza?

It is a moral catastrophe. I never imagined that the Israelis would reach this extreme. I have always said that Israel is the only democracy in an undemocratic Arab world. And that, in principle, makes you sympathize with them. But that has faded over time. It is impossible to sympathize with someone who is committing murder. And you see, I never used the word 'murder' and had many discussions with my colleagues. I always said that in wars there were no murders, only dead and collateral damage. Soldiers are killed because war is like that, it is inevitable. But what Israel is doing is indeed murder, and systematic. They have crossed that line, and that is intolerable. This level of impunity has never been reached before.