When writer Andrea Marcolongo was sitting on a terrace in Paris, she did not understand the runners who, while drinking wine with friends, took over the streets in flocks. Around her, dozens of people either fled or ran dressed as athletes. She did not know then that the runners had the same questions in their heads: What's the need? Wouldn't it be better in a bar? Is it possible? Am I running? Can this be considered running? Shouldn't I just go back home? What's the need?

The masochistic impulse to interrupt the routine to meet the goal of enduring running through the city for the promised kilometers apparently has a philosophical background. Andrea Marcolongo connects the society hooked on performance tracking apps - and dressing in an "ideal outfit" for sports - with Ancient Greece. The classical philologist, journalist, and Italian writer relies on Philostratus of Athens, a rhetoric professor and philosopher, who in De arte gymnastica equates sports with astronomy, geometry, music, medical science, painting, sculpture, and engraving: "Gymnastics is a knowledge not inferior to the others," wrote Philostratus, who had not tried low-cost gyms.

Marcolongo, a graduate in Classical Literature, decided to start running to find meaning in the addiction to running without ever having run before. "It was horrible," she admits on the other end of the video call. "I felt an infinite shame. And not just on the first day. 100 days later, I still felt ashamed. I couldn't run for even a minute. It was too much for me. I remember it very well. My face was all red. I felt a lack of intellectual dimension. Nowadays, millions of people run, but they don't know why: in the ancient world, sports were part of intellectual preparation. It was almost a philosophical exercise. The association that Philostratus makes between the decline of the thighs and spiritual decline is very important."

That embarrassed day she started a training plan that would give her the endurance to complete the 41.8-kilometer distance separating Marathon from Athens, the route traveled by the first marathon runner in history, the messenger Pheidippides. He carried the message of victory in the Battle of Marathon. "We have won," he said before dropping dead from the effort. Too epic. "It's a myth. Anything important has its corresponding myth in classical Greece. The act of running as well. My favorite myth has to do with the interpretation of kairos. It speaks of time in an almost figurative sense. It's the idea of not running behind time, but standing in front of it, stopping it, and taking advantage of it."

And with running, in the quest for the holy grail of the runner, she has achieved it. She entered the wormhole where concentration, suffering, and repetition build a small individual paradise, a bubble of pleasure through pain. "In short, after spending a whole life tormenting myself to understand what time is, running has freed me from that tragically Proustian obsession and immediately, with no escape possible, has imposed another: understanding what is inside time," can be read in The Art of Running. From Marathon to Athens, with wings on your feet (Taurus), the manual that explains this centuries-old obsession with continuous running. "It's a book not aimed at athletes. It's made for people who knew nothing about these things. In a time where we love to lie a lot, with running you can't lie. You only have your legs. You do what your body can do," she points out.

"I cried. I didn't know the possibility of ecstasy existed. I felt alive, aware of my body. Mortal and immortal"

From her training, the author draws the ideas that shape the book. She experienced fatigue. "For me, starting to run was as hard as continuing to run. For months, it was torture." She felt nostalgia. "It has to do with the loss of freedom. Nostalgia for the afternoons when we were children." She experienced ecstasy. "I cried. I didn't know the possibility of ecstasy existed. I felt alive, very aware of my body. It happened to me five times. I felt very mortal while being immortal at the same time. She felt like another element displayed in the street showcase. "It's exhibitionist. Very narcissistic. The runner puts on a show. Major races occupy public space. It's the only time many people come together with others. There are no longer assemblies or meetings to share common interests, but every afternoon, every Sunday, runners gather."

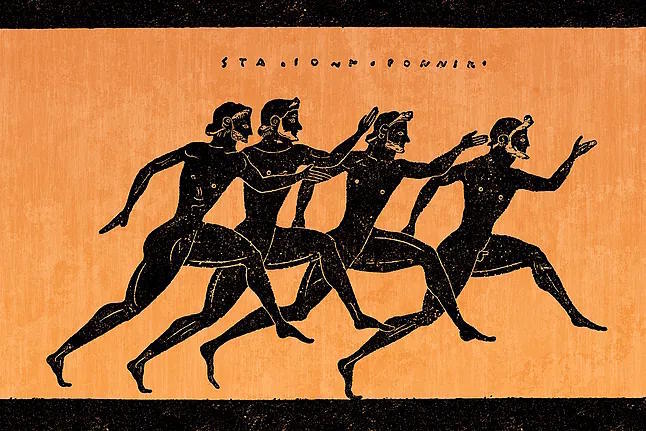

In classical Greece, races were very different. Both in distance and purpose. There was no way to know at what pace they were running. "They were more practical. They ran out of necessity. To deliver a message, to prepare for war. The idea of resistance in effort is not very Greek."

Our society runs and is overweight and has an obsessive relationship with well-being and health. "Never before in history have there been so many overweight people and so many people doing sports. Sports take up a lot of space in young people's lives. It takes a lot of time to run an hour a day."

Searching for the philosophical meaning of running - "I insist on running because it's the most concrete way to feel alive" - changed Marcolongo's life.

Spoiler: she completed the 41.8 kilometers of Pheidippides. "I was exhausted, it was cold, and I wanted to take a very long and very unecological shower. I had done it. And at night, hours later, it's not that I had forgotten, but I thought it would be more grandiose," concludes a whole theoretical apparatus of footing.