There is a high probability that Donald Trump shares genes with Tyler Robinson, the killer of influencer and conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

Hold on a minute before shouting "fake news!". We know that Robinson, 22, grew up in a staunchly Republican family, with principles as immovable and conservative as those propagated by Kirk himself. And that, after taking out his target with a shot on September 10, he sent the following message: "Why did I do it? I couldn't take his hatred anymore, there are things that cannot be negotiated."

Do not miss and retain this idea. A week later, Trump himself suggested something similar - that there are things that cannot be negotiated - during Kirk's funeral: "Charlie did not hate his opponents and wanted the best for them, that's where I disagree with him: I do hate my opponents and I do not want the best for them!".

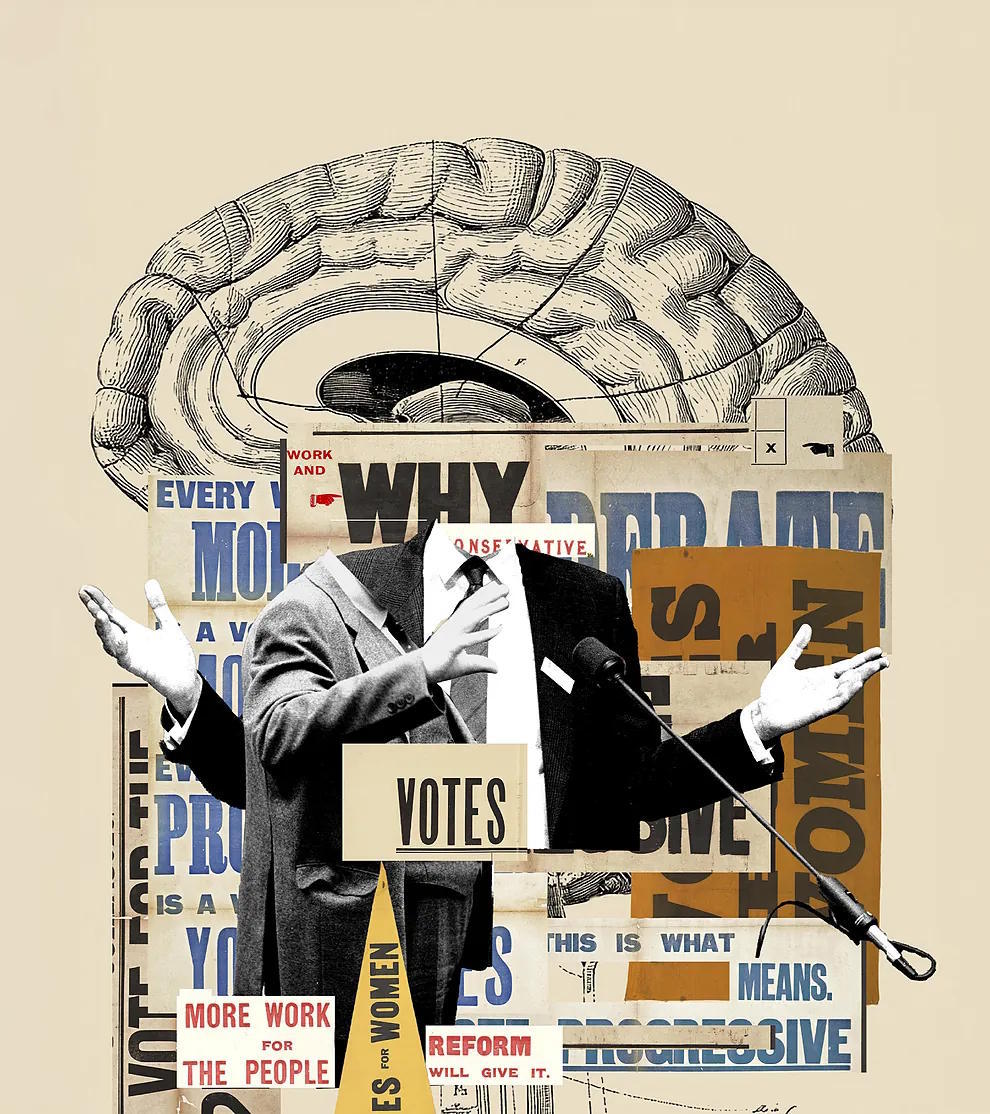

Here is the key. Robinson's savage attack and Trump's subsequent outburst trying to censor voices against him have a common factor: their disproportionate way of reacting to stress, which activates mechanisms marked by their genetic basis. "The extreme left and the extreme right share psychological traits: factors that explain not what they believe but how they believe it," explains neuroscientist Leor Zmigrod via video call, a professor at the University of Cambridge and a pioneer in a new branch of her discipline, called neuropolitics.

This 30-year-old psychologist - yes, only 30 - publishes today in Spain The Ideological Brain (Ediciones Paidós), a highly acclaimed essay translated into twenty languages that reveals the hidden mechanisms that shape our political, social, and religious beliefs. After conducting a wide range of neurological and biological experiments in her laboratory, the author reaches the following conclusion: "All humans exist along a spectrum where some are more prone to rigid and ideological thinking and others to more flexible and ambiguous thinking. But what really influences our radical thinking and drives us towards extremes is a determining factor: stress."

Why being a Barça fan, eating tofu, and having sex is left-wing, and being a Real Madrid fan, enjoying flamenco, and making love is right-wing

How polarization has ended moderation in Spain

In other words, there are heritable factors, whether it is the configuration of genes that distribute dopamine in the brain or how we respond to the perception of a threat, that determine whether we are obstinate and dogmatic thinkers or, on the contrary, independent and flexible. And then, on this genetic basis, various environmental factors such as the perception of threats to our survival or individual well-being alter the functioning of our brain to the point of pushing the ideologies we believe in to extremes.

"Most brains, even the most rational and intelligent ones, seek clarity, coherence, and certainty," explains Zmigrod. "They are predictive organs and constantly try to explain how we should behave. When the answers are not clear, ideologies come into play, which are very seductive because they appeal to the need for order in our brain. In situations of stress and uncertainty, our minds become more rigid, optimize resources, and instead of exploring, being adaptable, and listening to reason, they think in a more limited, discriminatory, and prejudiced way against those who are not part of our ingroup."

"As long as we continue to glorify rigid thinkers and encourage them to remain faithful to their beliefs, we discourage people from seeking a more flexible approach"

External factors such as social exclusion or the perception that there are not enough resources for everyone contribute to exacerbating that feeling of stress. "These ideas are one of the tools that propagandists use to influence us," Zmigrod recalls. "Their goal is to make us feel threatened in order to make us malleable beings."

Faced with the fear of the unknown, certain individuals cling to routines and habits. Their brains lean towards explanations of an ideological narrative acquired previously, which acts as a narcotic against the unpleasant feeling of the unknown. "We anesthetize ourselves against change," says the researcher about a mechanism that, essentially, is synonymous with an ideology: "It is a very limited system of rules that explains the world, which resists facts and leads people to form highly tribalistic identity groups. It causes them to dehumanize those they disagree with, but it also leads them to dehumanize themselves."

Zmigrod found out how the brain of a radical person works in her laboratory. In one of her tests, she subjected a wide sample of people to relate shapes and colors. After internalizing the rules and patterns of the test, those who became frustrated with a change in its functioning, who could not adapt, who took longer, or who became stressed by the system changes tended to be the most dogmatic thinkers. "They are the brains that resist listening to alternative points of view, that distress at an argument that does not fit them because they take it as a personal attack," she explains.

Neuroscientist and author of 'The Ideological Brain', Leor Zmigrod.TOM JAMIESON

This is what Zmigrod calls "cognitive rigidity," a trait that helps us identify when there is a higher risk of falling into dogma. "Information processing in dogmatic brains is slower," the researcher concluded. "That is why they tend to be more impulsive thinkers: they make premature decisions because it takes them more time to understand sensory information compared to more flexible and less prejudiced thinkers, who take less time."

Let's revisit the example of the young killer Tyler Robinson, an extreme example of "cognitive rigidity." While his family was deeply Republican, he chose to switch to what he considered "the right side of history": radical left-wing. "Even if you believe that your ideology is the right one, as most humans do, you run the risk of falling into the spiral of radicalism when you start thinking that a political cause justifies certain extreme actions," she explains. "All ideologies demand that someone be a prototype, so I think that, from the individual's point of view, it is contradictory to speak of a good ideology, because they all work like this."

One method to avoid succumbing to extreme ideologies is to actively act against our most primitive instincts and our most ingrained habits. "Nothing is predestined," she insists. "Just as we choose one idea over another, we can also choose between a more flexible or a more rigid way of thinking. The problem is that right now we live in a society that considers flexibility as a trait of weakness." Being open to change and considering all nuances indicates that you do not have a firm stance, when in fact it is the opposite: flexibility is the most difficult stance to maintain.

We said that Robinson and Trump share the rigid idea that 'there are things that cannot be negotiated.' Does this concept come from their genetic basis or is it something they have acquired through their environment? Here, Zmigrod's essay faces a circular dilemma: whether it is our brain that shapes our ideas or, conversely, it is our ideas that end up altering our biology. "Nothing is determined," Zmigrod points out. "The most important thing is that we choose not to succumb to the ideological experience."

There are people, warns the young doctor, who grow up in "highly ideologized ecosystems, with strictly defined rules and hierarchies." Those contexts, no matter what ideas they defend, can turn even the staunchest believer in free thinking into an extremist. Thus, she introduces a new axis in our ideological brain: it's not so much about being left or right, but about choosing radicalism or moderation. "It's a personal choice, not just political, that reflects what kind of human being we are," the scientist values.

The results of Zmigrod's experiments coincide on another aspect: brains that release more dopamine in the amygdala - the part of the brain responsible for detecting threats and managing emotions - are also the most dogmatic. "These factors can lead to all kinds of biases in social and political life, but also in psychological life," she explains, adding that many forms of ideological thinking are also prisons: "They try to erase your freedom and make you a militant of a cause instead of an ambiguous person with nuances."

The tests proposed by the doctor - "shape and color games that have nothing to do with politics" - reveal how each mind learns from its environment. In this sense, the influence of social networks on how we receive information is relevant; especially political information. "It's an ecosystem designed to radicalize you," warns Zmigrod. "When you place vulnerable minds in an environment that benefits from consuming viral and extreme content, you facilitate a terrible recipe to make people prone to political violence, to make them support it, and sadly, many people do."

The social and imagined audience component provided by the networks in which we interact, combined with the thought structures cultivated during our upbringing and our genetic predispositions - such as our cognitive rigidity - equally affect how we defend our values. "I believe there is a difference between ideologies and life philosophies," the author points out. "Being against ideologies doesn't mean you can't have morals. If anything, it sharpens them because you care about causes with all your humanity and not because someone told you to. But as long as we continue glorifying rigid thinkers and encouraging them to remain faithful to their beliefs, we discourage people from seeking a more flexible approach to life."

In 2019, Anthony Loyd, a journalist from The Times, found in Syria Shamima Begum, one of the three girls who, four years earlier, without finishing school, ran away from her home in London to support ISIS during the peak years of the terrorist group in Iraq. The Boris Johnson government revoked Begum's nationality after she stated that she had no regrets, that seeing beheadings did not affect her, and that the murder of some journalists was justified. Her case captivated Leor Zmigrod. "We see how people change: there are individuals who voluntarily choose a less free way of life, highly influenced by their emotional, cognitive style, and biological traits."

For Descartes, the lowest degree of freedom was choosing between indifferent things. Yielding to an ideology is exercising free choice, but Zmigrod adds that "we live in a world where not everyone chooses to be free": "Beneath that first layer, we see that society itself does not always guide us towards full freedom, because society, as a social organization, may not be interested in individuals being completely free."

That's why profiles that leave behind the most ideologically charged environments in which they were raised are so interesting. In that sense, the researcher points out that there is a psychological trait that can drive these forward escapes: creativity. And the most important lesson is that, regardless of genes, "we can always cultivate it."

"True creativity is the one that doesn't follow the rules, the one that plays with directives and assumptions," Zmigrod insists. "By infusing our mental life with it, we develop a kind of psychological elasticity, and from there we learn to face everything. But working against all the restrictive forces that stand in our way is a constant effort that lasts a lifetime."