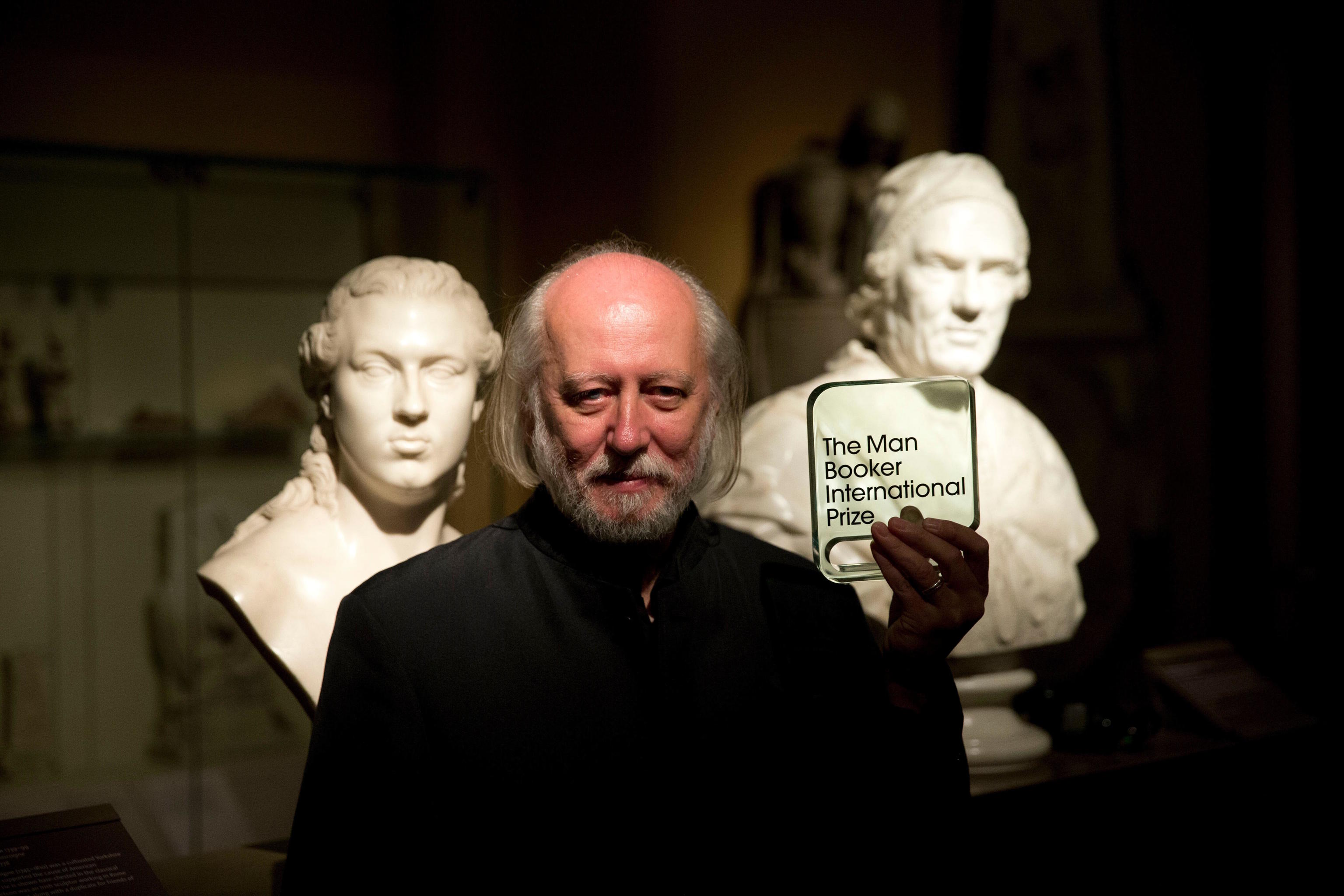

At first glance, László Krasznahorkai does not show melancholy. Nor a fierce gesture or a significant grimace against anything. A wandering Hungarian, in his writing, he sharpens the terrible. I mean: his is a powerful expression of a citizen driven by ideas for which he needs literature, a disquieting, delayed literature, willing not to give in. A writing made of adverse ideas.

He acknowledges his lack of sympathy for journalists, distrusts politicians, does not believe that this world can be fixed. He travels and knows. He observes and confirms his disagreements. He belongs to the lineage of writers who demand time to delve into their density (Bernhard, Cartarescu, Handke...) and seems not to mind being somewhat alone most of the time. It's normal that he collaborates with a dense film director like Béla Tarr, of whom you don't know how much is cinema and how much is an overdose of his Hungarian condition.

László Krazsnahorkai is also in line with the spirit of a poet who has nothing to do with his tradition, but is close to his priorities: Fernando Pessoa. Authors with a particular encoding. Both work with a beautiful purpose: to amplify the language. If you come out whole from the reading, you can guess their literary ambition, that vocation to understand the craft as a way to broaden consciousness. The recent Nobel laureate shies away from the new manners established by digital culture: exhibitionism, manipulation, the perverse fiction of deliberately confusing the real. Not for being outside the norm, but by his own norm, by pure protest and by renunciation of the obvious.

In Krazsnahorkai's novels, desolation functions as a pole vault. And his country, Hungary, is the representation of what is shattered, an absurd and dangerous construction. It all began when he understood what it meant to glean in a communist country and how it instantly breaks down any alternative to its oppression. It may be one of the roots of his work, that perplexity and rejection upon realizing how much lacks sense in this dog-eat-dog era. And yet, reading him brings something joyful, a burst of poetry that enhances estrangement. A defiance of inquisition, frivolous solemnity, and the puritanism around.