Legend has it that many Nobel Prizes in Literature throughout history have been decided in a bar. Not just any bar, privacy dictates, but a particular one. As Den Gyldene Freden's slogan warns: "Genius and chaos since 1722". The Swedish Academy bought the historic building where the establishment is still located in 1920. In exchange, they have had one of their best lounges reserved every Thursday night between February and May for a very special mission: nominating the finalists for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Rumor has it that pea soup is always on the menu. The sharpest tongues add that the alcohol bill from those meetings is not exactly cheap and that the noise of the discussion can be heard from every corner of the restaurant.

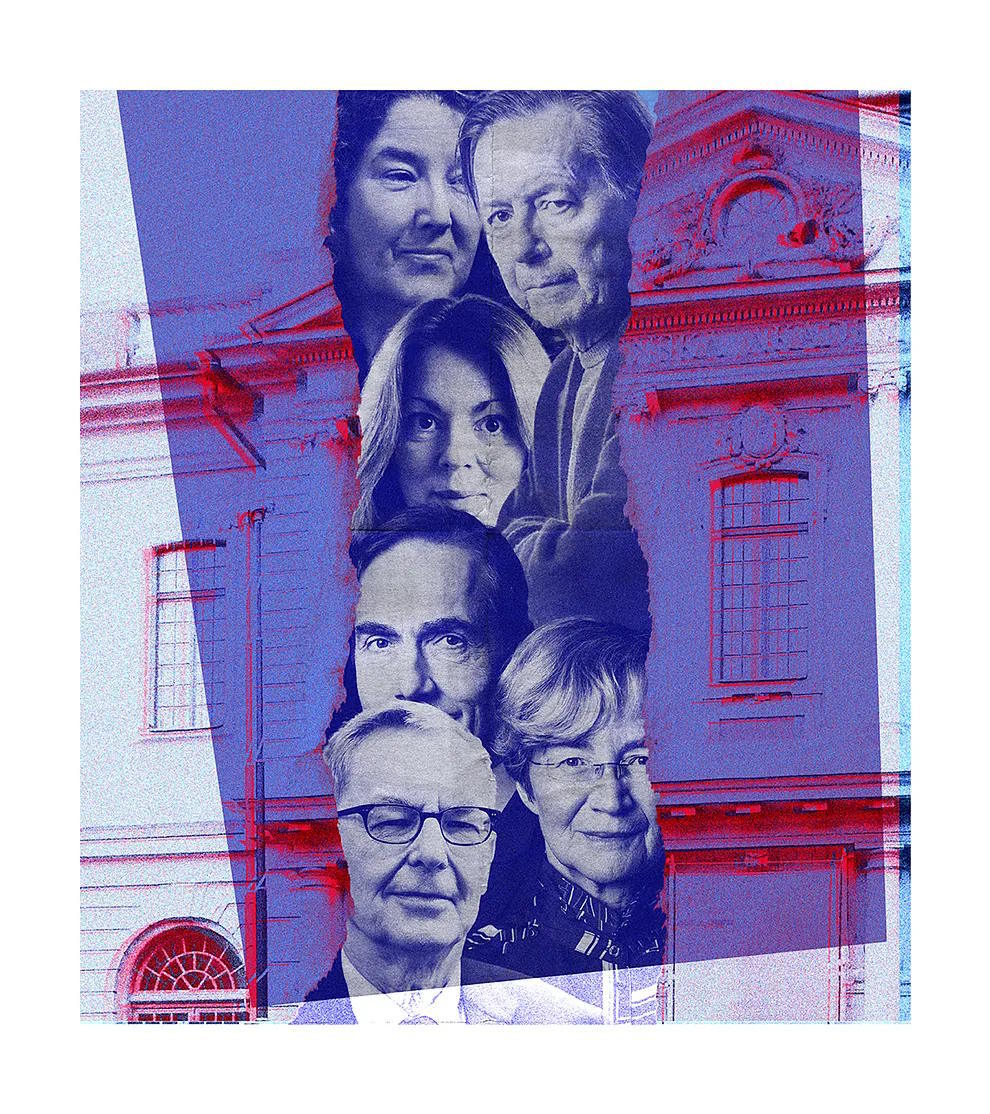

The five members of the Nobel Committee, chosen from among the 18 members of the Academy (now actually 17, but we will come back to that empty seat later), are responsible for compiling the final list of names to be voted on in the plenary session. The writer and university professor Anders Olsson chaired the Committee that awarded the prize to László Krasznahorkai, composed of the novelists Ellen Mattson, Anna-Karin Palm, Anne Swärd, and the journalist Per Wästberg. It was the first time that there were more women than men on the committee, a compensation for the historical lack of parity that has also been reflected in the winners: in the last decade, exactly half of the Nobel Prizes in Literature have been awarded to female writers.

"I believe there have been few mistakes in that," says Javier Aparicio Maydeu, Professor of Comparative Literature at Pompeu Fabra University, literary agent with Carmen Balcells for 15 years, and literary critic for three decades, emphasizes: "In that." "Reflecting female talent is in line with the times, and only a fool would condemn it," he adds.

It has been clear since the inception of the award that literary quality is not the only criterion for selection. "Just look at the list of winners to see a false dominance of French literature in the early 1900s that later shifted to English-language literature, and that axis continues," analyzes the professor. "Italian, German, or Spanish literature has been mere splashes in decisions clouded by a clear geopolitical criterion that has intensified in the last 20 years towards a postcolonial perspective, replacing the much-criticized Eurocentrism."

The Nobel Prize awarded to Chinese author Gao Xingjian opened a door that increased the professor's disillusionment until Bob Dylan's award in 2016 definitively broke his heart. "Postcolonialism is a fundamental theme in culture, but it has turned the Nobel Prize into a more surprising mechanism than it should be, with awards going to unknown authors from remote countries with few readers and who have barely been translated. It doesn't make much sense," he asserts. And confirms: "It has increasingly become a lottery. The best are not always rewarded, no."

But before reaching that 2016 when all predictions went out the window, let's break it down, because in the selection of the Nobel Prize in Literature, two processes are involved: the chronological and the human, and without knowing the former, it is difficult to understand the latter.

The clock for the next award starts ticking as soon as the new laureate is announced, and the Swedish Academy begins to receive thousands and thousands of letters with thousands and thousands of nominations from university professors, academics, accredited representatives of the writers' guild, and of course, previous laureates. The Literary Administrator faces the titanic task of turning the flood of suggestions into a list of approximately 200 names, long but intelligible, throughout the month of February.

These weekly meetings will be the focus of discussion, ending late at night with pea soup at Den Gyldene Freden, just five minutes downhill from the Academy. More convenient, impossible.

In April, the sifting begins. The Committee members present about twenty semifinalists to the Academy, listen to their arguments, and lock themselves away to thoroughly study the proposals and narrow down the list to five finalists from whom the winner will emerge between September and October, voted by an absolute majority. Each Committee member must prepare a detailed report on their favorite candidate, and may rely on linguistic and literary experts for this. Discretion must be paramount in a series of meetings whose minutes remain secret for the next 50 years, although it has not always been the case.

Lately, the human factor has interfered with the chronological process, and in a significant way. In November 2017, 18 women accused French-born photographer Jean-Claude Arnault, married to veteran academic Katarina Frostenson, of sexual assault. The investigation, which resulted in a conviction, also revealed that the Academy funded the cultural center Forum, run by Arnault in Stockholm, a regular meeting point for the cream of the crop of the Swedish cultural scene, and that, as a result of these relationships, the photographer had leaked at least seven Nobel Prize in Literature winners between 2006 and 2016 to betting houses. Three academics resigned, including permanent secretary Sara Danius. The prize was suspended in 2018 for the first time since World War II. The Academy changed its statutes, and committee members now have a three-year term limit. Frostenson's seat, number 18, remains vacant to this day.

However, for Professor Aparicio Maydeu, the sexual scandal that shattered the international image of the Academy and made it a laughingstock has not had as much influence on the selection of the new Nobel Prize in Literature as the tsunami that occurred a couple of years earlier. "For me, the turning point came in 2016 when they awarded the prize to Bob Dylan," he asserts. "The Nobel Academy had been playing with marketing campaigns for some time, moving away from the norm in search of media attention, but that was a radical change in the rules of the game without warning the participants. The fact that the singer-songwriter himself didn't give it much importance shows they were wrong. Marketing campaigns don't always align well with the complexity of the world. Even less so with the literary world."