At the beginning of The Sinners, one of the box office sensations of 2025 and a strong Oscar contender, Ryan Coogler introduces the figure of the griot as "people born with the gift of making music so authentic that it can penetrate the veil that separates life and death, invoking spirits of the past and the future, with a gift that brings healing to communities and also attracts demons." And one expects the griot who is about to arrive, something like a totemic figure in the countries of West Africa, to appear as a divine apparition. Nothing could be further from the truth.

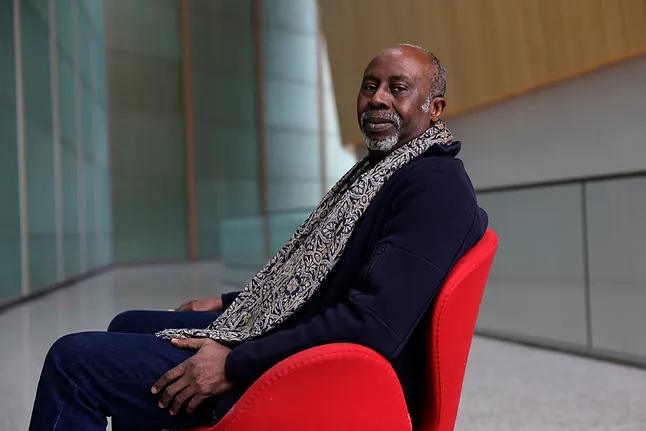

Hassane Kouyaté (1964) speaks with a slow cadence, with a minimal tone of voice and with absolute affability. Born in Burkina Faso, into a family where griots have succeeded each other since the 13th century, this man dressed entirely in navy blue, only altered by a flowery scarf, grew up in his community until at the age of 20 he went to France, following in the footsteps of his father, the actor Sotigui Kouyaté. The son grew in the theater to become - here as well - a totemic figure in this discipline. For years he served as artistic director of Peter Brook's company, a pope of contemporary theater; since 2019 he has been directing the Les Francophonies festival in Limoges and with his works he has traveled through America, Europe, and Africa. He now premieres Where Do We Come From? at the Teatros del Canal, created in collaboration with Santiago Sánchez, director of the L'Om Imprebís company and who acts as a translator in this conversation.

"I am the result of the encounter of wonderful people, of great women and great men, of my mom and my dad to start with. All the people I have met in life have given me good learning. Even those who have hurt me have made me grow. Everything has been the result of encounters. For example, for me to be here today, there was a previous encounter, mine with theater and with Santiago," says Kouyaté, whose community role as a griot is to be a historian, mediator, organizer of ceremonies - weddings, funerals...-, teacher, psychologist, and also a political figure. That's why his theater is imbued with that historical and social burden, with Africanist narratives, and of course with his tradition.

In Congo Jazz Band, the Burkinabe addressed the violence suffered by Belgian Congo during the colonization years. In Black Star, he explored the life of Marcus Garvey, one of the leaders of 20th-century Pan-Africanism. And now he is finalizing another show about the fight against apartheid of South African singer Miriam Makeba. "I am still one of the few people who can take a political stance, I have that obligation," says the playwright. And he continues: "As my role as a griot obliges me to be partly a historian, I believe it is important to know where we come from or where the things we have experienced come from. For example, Donald Trump. Is he a product of chance? No, he is the consequence of slavery, imperialism, and colonialism, of the domination of some human beings over others. Because this did not start now, we are a society that has not buried its dead, we have them hidden in a closet. If we do not bury them, this society will not be well."

And there Kouyaté launches into a dissection of the world passing through the racial conflicts that multiply in the United States and also in the France where he lives until reaching the root in the African continent. "Today there are two great peoples: the dominant and the dominated. The European man is made to believe that he is better than the African because there they are with wars, poverty, and hunger. But all of that is already being suffered by Europe as well," explains the Burkinabe who in his work on Congo emphasized a premise that he repeats today: "we all carry a part of Congo in our pockets." He refers to the uranium from which our mobile phones, tablets, computers are made... "Many young Africans do not know the history of slavery in Africa and partly it is because they have been in schools with Western education programs. My nephews, educated in Burkina, do not speak any of the country's original languages. I am not against the idea of a nation, but I believe there is something richer than nations, and that is the culture beneath them."

His theater seeks precisely to challenge these young people, so that they can approach African culture in theaters around the world to find their origins that he absorbed until the age of 20, maintaining his life in Burkina. "I have understood that my parents wanted me to root well first and then I could open my branches towards the four cardinal points. Nowadays, young Africans are like poorly baked cookies. Their two sides are burnt, but inside they are raw. How are they going to face the bulldozer coming at them with means controlled by the dominators? It is very difficult because the moment you lose control of education, you have lost control of humanity," reflects Kouyaté.

The answer he finds lies in words, dialogue, theater... Ultimately, in what he appeals to in Where Do We Come From?.