In 2012, the Obama Administration, the European Union, and Japan brought an unprecedented dispute against China to the World Trade Organization. It was the international reaction to the emergence of a new geopolitical weapon that today, just like back then, belongs exclusively to Beijing: a cut in the trade of critical minerals capable of halting the global economy.

China first resorted to it in 2010 against Japan as a counteroffensive in a dispute over fishing boats. Ten years passed until, in 2023, it activated it again in response to the barriers set by Joe Biden's White House on the flow of chips and other technological equipment made in America. This year, Xi Jinping's government has reacted to Donald Trump's tariff war by once again turning the key to global technological development, by banning the export of seven of the 17 elements that make up the so-called rare earths, a group of chemical components (scandium, yttrium, and the 15 lanthanide elements) as difficult to extract as they are vital for the digital, military, and energy advancement of the entire world.

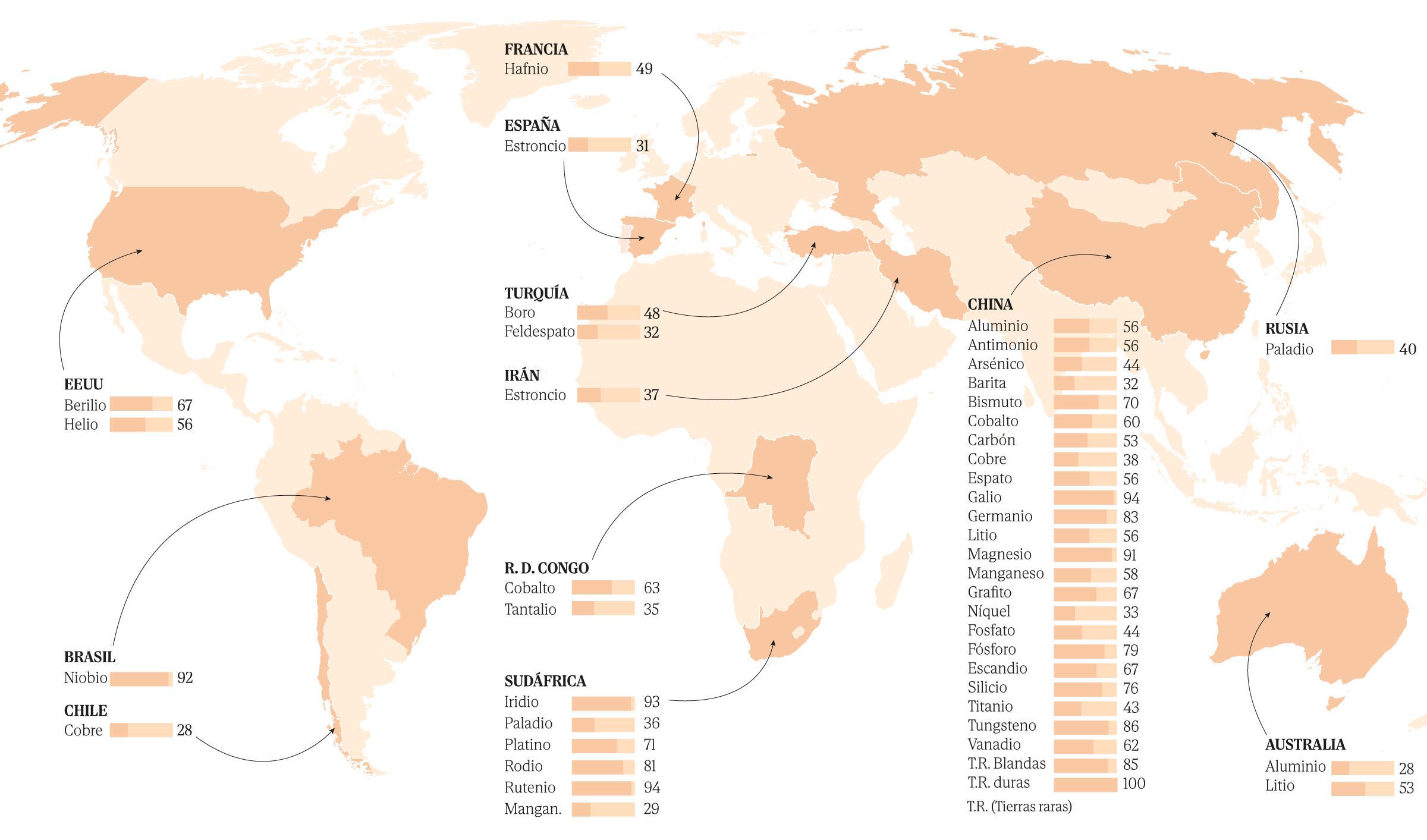

In 2012, China held a quasi-monopoly in the global market of critical minerals. That remains the same, as Beijing continues to be the largest global supplier of most critical raw materials, with close to 100% shares in rare earths, magnesium, or gallium. But something has changed since that dispute. The United States, Canada, and especially the European Union have significantly increased the signing of bilateral agreements with governments of countries abundant in these minerals in the last two years, mostly emerging or developing economies in Africa and Latin America.

It is the diplomacy of critical minerals, where transparency is scarce and gray areas abound. Contrary to the "take or pay" contracts that in oil and gas protect importers and exporters with million-dollar compensations for any breach, concepts like strategic partnership, letter of intent, or memorandums of understanding (MoU) are emerging here. These are cooperation mechanisms between the country with the mineral and the one in need of it. Although their goal is to mitigate supply risks and strengthen the value chain of these raw materials, their commitments are not binding. It could be said that the semiconductor industry and global trade in clean energy, cybersecurity, technology, artificial intelligence, or defense depend on the goodwill and mutual interest between governments of all kinds. A marriage of convenience where, in general, backtracking does not entail legal repercussions.

Actualidad Económica has had access to the complete list of intergovernmental agreements on critical minerals compiled by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the energy arm of the OECD. From 2020, when their records began, to 2023, the last complete year, the annual number of alliances went from two to fifteen. More agreements were signed in one year than in the previous three combined. Although publicly disclosed agreements are still few, their frequency increased by 650%. In the first six months of 2024, eleven more agreements were sealed, almost as many as in the entire previous year and more than in any other year in the historical series. The European Union stands out as the entity that has signed the most alliances, while China, despite controlling mining and refining of mineral resources scattered worldwide, is notably absent.

"China started moving 20 years ago, deploying a network of mining companies in all those countries with reserves of certain raw materials that were already known to be critical for later periods, due to energy or digital transition. The country has become an expert not only in extraction, which is extracting the stone, but also in refining. For example, with rare earths, they have a significant advantage over any other country that could now start refining them," explains Águeda Parra Pérez, a geopolitical and technological analyst of China, Founder and editor of ChinaGeoTech. In summary, China has its own reserves of many strategic minerals, and for those it does not have in its territory, it has secured them by deploying a battalion of state-owned companies where the resource is located. "They are there in extraction, and then they take the refinery to mainland China," she adds.

"We have become addicted to critical minerals. China was the first to see it coming and acted. There are countries that are major producers of a certain mineral, but where do these elements go to be processed? To China," explains Miguel Golmayo, a member of the Spanish Navy and an expert in energy and military intelligence. In his latest book, La fiebre del oro verde (Planeta, 2025), he defines raw materials as the "hidden challenge" of an ecological transition that has exacerbated "China-dependency." "The West has realized this and has reacted, hence Trump's interest in Ukraine or Greenland. It's not that he likes the ice, he looked at the map and saw where the critical minerals are and where China already is. The United States has arrived late and poorly, and now it wants to grab what it can of what's left."

From Strasbourg, socialist MEP Nicolás González Casares defends the EU's modus operandi in this frantic race for underground treasures. "For the European project, the search does not involve the coercion and blackmail practiced by the Trump Administration, with a colonialist attitude, to force external production." At the other end, Casares places China, with vertical control from extraction to refining thanks to an infrastructure diplomacy linked to the Belt and Road Initiative, the cornerstone of the country's foreign policy that combines massive investments, loans, and infrastructure development in exchange for preferential access to critical resources. "China has extensive experience in engaging suppliers to whom it offers investments in exchange for resources, without environmental or political considerations. It influences, assists, and does not make labor or environmental standards a concern," notes the MEP. And in the middle is the EU.

"We cannot and should not opt for blackmail; we do not have the military power of the US, and we care about environmental sustainability and labor rights. The EU must opt for mineral diplomacy, balancing its strategic interests with respect for multilateral rules, sustainability, and mutual benefit," asserts Casares.

According to Golmayo, the EU's big mistake has been that each country has pursued its particular interest: "They know it in the United States and they know it in China, and that's why whenever negotiations are needed, they prefer one-on-one dialogue and avoid dealing with all 27. The EU is necessary; if we separate, we are lost." "It has been a bad practice not to have a single voice in Europe for negotiations. We saw it with Russian gas. Each European country fought on its own, thinking it could solve its energy problem individually. But now we are moving towards a European mission because you always have more strength when negotiating a contract for 400 million people," reinforces Fernando de Llano, associate professor and researcher at the University of A Coruña, an expert in energy economics.

For the professor, the keyword is negotiation. "We are not in the colonial scheme that existed before; that doesn't work now. Now there is a negotiation between two countries seeking to win." And he points to one step further: compliance. "Many minerals are in countries with problems of corruption, geopolitical instability, institutional fragility... Europe needs real compliance, not to face supply problems, for example, due to coups d'état," warns the expert. The Union, he concludes, is facing a dilemma: "It is facing itself because it is talking about integrating into its value chain supplier countries that do not respect human rights."

More than 60% of the world's cobalt supply comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, around 50% of nickel is extracted in Indonesia, 71% of platinum, over 90% of iridium, and about 30% of manganese come from South Africa, and more than 23% of copper comes from Chile. Focusing on Europe, the Twenty-Seven, apart from China, depend on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which supplies 68% of its cobalt, or Chile, which provides 78% of its lithium. Therefore, to understand the choreography of alliances that governments dance to, one must put oneself in the shoes of emerging countries.

More than 12,000 kilometers and six hours ahead of Brussels is Chile, one of the world's largest producers of copper, lithium, and iodine. A few days ago, the Government of Gabriel Boric established, with a ceremony at the Palacio de la Moneda, the High-Level Advisory Committee that will lead the country's critical minerals strategy. Comprised of companies, academics, and politicians, the objective is to position Chile as a global reference in these resources. "The strategy of alliances is increasingly common in the energy and economic policies of countries. It is especially important in critical minerals investments because they have long-term repercussions," explains Dorotea López, director of the Institute of International Studies at the University of Chile and one of the 16 members of the mentioned Committee.

What does Chile gain in this alliance game? "A good strategy can attract investment and boost infrastructure, such as roads and ports, and access advanced technologies and knowledge," she argues, although she ensures that the impact always depends on the "content" of the agreements. In Chile, she states, "we must have a roadmap to define alliances that must always be beneficial for both sides." The European Union and Chile signed an update to the framework agreement governing their bilateral relationship in December 2023. They had been negotiating a new framework, unsuccessfully, since 2016.

EUROPE'S CHINA DEP

More than ever, in the geopolitics of minerals, information is power. "There is no reliable global data on the actual volume of reserves of these critical elements, so producing countries play with what they say and what they keep silent," De Llano points out. Since 2011, Brussels has its own list of critical materials that it updates every three years. Minerals are added or removed based on an equation that considers their importance to the community economy, demand forecasts, and supply risk. In the latest review in 2023, the EU removed two elements and added six, increasing its list from 30 to 34. A decade ago, it evaluated around fifty candidate materials, but in the latest update, it analyzed 70.

Not all countries with minerals are suitable for alliances. "There are many territories where reserves have been identified but their exploitation later turns out to be unfeasible," explains Parra. Sometimes the barrier is economic, and other times, it's temporary. Untapped reserves can mean 10 to 15 years of work before starting to extract the mineral. "The European approach is to seek partners with reserves already in production because primary exploration takes time that we cannot afford."

Parra rejects the idea that Europe should avoid places where Beijing has already made its mark. "China has engaged in global diplomacy and is everywhere, in trade because it is the largest partner of over 150 countries, and diplomatically." The U.S. has a certain degree of self-sufficiency, but the EU depends on China. "Our aerospace and military industry would be at risk in case of a rupture. We wouldn't be able to manufacture night vision goggles, missiles, drones, or anything that is considered essential in any armed conflict today."

Trump's offensive urges the EU to ensure a stable flow of critical materials. The issue is that many of its alliances are in the initial phase or still under negotiation. The Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies warned of this vulnerability this month: "Europe must rethink the rules of globalization, starting with strategic sectors such as semiconductors, critical minerals, or batteries (...). For now, the European industry needs to continue in China. The wave of protectionism, isolationism, and instability unleashed from Washington should serve to strengthen the domestic market and the continental political identity, and to fulfill defense duties."