In a busy establishment of a Western food restaurant chain near the People's Square, in the heart of Shanghai, a sign has been posted on the door explaining that they have stopped buying beef from the United States due to Donald Trump's high tariffs. Now, they source the meat from Australia. One of the managers explains that they chose to announce the change because, amid a growing wave of Chinese nationalism calling for a boycott of American products, they thought the announcement would attract more local customers. And it did. "There were influencers who shared it on social media, and now we have many more customers," the manager says.

With tariffs of 125% on imported American products, restaurants are switching from American beef to Australian beef, the quantities of wheat and liquefied natural gas that the Chinese used to buy from the US are now sourced from Russia, the same goes for soybeans and beans, which are now mainly imported from Brazil.

On the ground, Chinese businesses have quickly mobilized to seek alternatives to American products while economic planning agencies have been downplaying the impact of the trade war for days and announcing measures to protect their economy and exporters hit by the 145% tariff imposed by Trump.

In the political arena, the strategy involves an endurance race that China is winning. On Monday, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs came out to refute the latest statements by the US president regarding their tariff dispute with the Asian giant: neither has Trump recently received a call from Chinese leader Xi Jinping, nor is anyone in China participating in negotiations with the US team to reach a trade agreement.

Despite the more conciliatory tone recently used by its rival, Beijing maintains its stance with fiery rhetoric. All the while, Chinese diplomatic muscle advances in its goal of gaining international support, even approaching old US allies such as Japan and South Korea, and launching a charm offensive in Europe.

After weeks of Chinese counterattacks to each tariff increase by Washington, many analysts in the Asia-Pacific region have concluded that Beijing is not willing to make concessions, as happened during the first trade war in 2018, which ended with an agreement two years later for China to commit to buying an additional $200 billion in US goods and services.

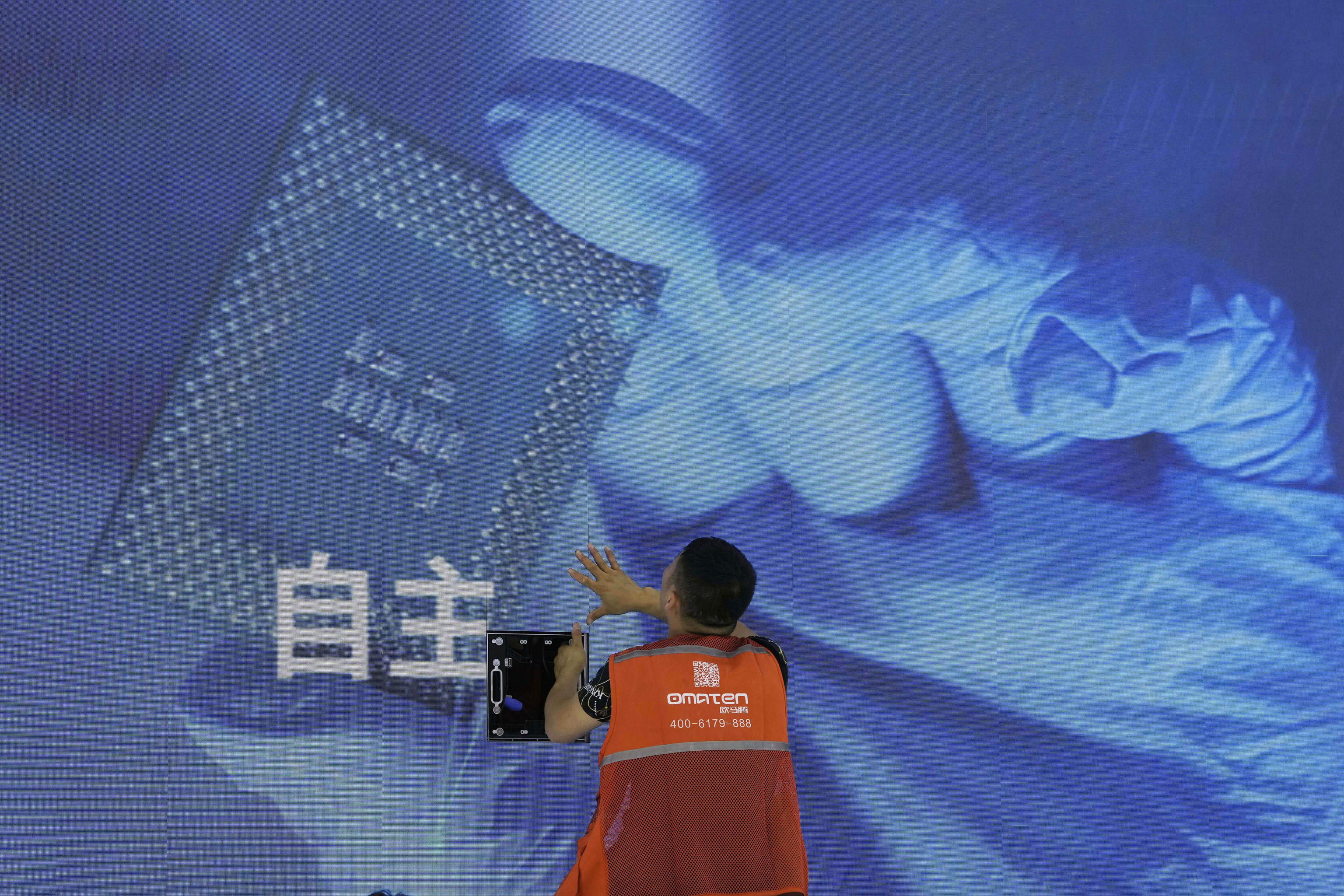

Now, in addition to responding with tariffs on American products, Chinese authorities have played with other weapons such as restricting exports of more critical minerals, crucial for US companies to manufacture chips and batteries, or including a dozen US companies on their export control blacklist. Although what Chinese state media have overlooked, to maintain their proud narrative of resistance, is that a few days ago authorities exempted some semiconductors manufactured in the United States from tariffs, in an attempt to protect their main technology companies.

Chinese official spokespersons have spoken out to reiterate that the impact of the tariff war will not be as harsh as predicted by the IMF, which last week reduced China's economic growth forecast for this year to 4% (Beijing maintains it will rise to around 5%).

"The government will implement a series of measures to support the labor market, encouraging companies to maintain stable hiring, intensifying vocational training programs, and expanding employment through public works programs," said Zhao Chenxin, deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, the country's main economic planning body, summarizing some of the guidelines set at a meeting last Friday by the top leaders of the Asian superpower, the Politburo led by President Xi Jinping.

The Chinese leader stated that in the coming months, several specific plans will be implemented (greater access to credit to boost technological innovation, a more proactive fiscal policy, and a moderately loose monetary policy, accelerating the issuance of government bonds and reducing the reserve requirement ratio and key interest rates) to support the companies most affected by the trade war.