"A Slow-Motion Catastrophe" (The New York Times), "A Volcano Ready to Erupt at Any Moment" (Harvard Medical School), "A National Embarrassment" (The Atlantic). These are just a few examples of how media and scientists in the United States qualify the current situation of the avian flu outbreak in the American country, oscillating between concern and criticism of the management by the authorities.

Although avian flu landed in the USA in 2022, it has been over a year since a significant turning point occurred: the virus jumping from birds to cows, a species that was believed to be safe until then. The news set off all alarms as we were facing an unexpected twist. But what happened next was also unforeseen, considering the resources and capacity of a country like the United States, as well as the recent terrible experience of the Covid-19 pandemic.

"We have had a year of inefficient management", states Elisa Pérez-Ramírez, a veterinarian and veterinary virologist at the Animal Health Research Center (INIA-CISA, CSIC). The number of affected dairy cow farms has already exceeded a thousand and they are spread across at least 17 states. "What should have been the number one priority, which is eradicating this virus in a livestock species like dairy cows, is now impossible to achieve. Clearly, they have not done much to stop this, and now it is quite late."

In the same opinion is Antoni Trilla, an epidemiologist and professor of Preventive Medicine at the University of Barcelona: "USA has a problem of probably unknown magnitude but surely at this moment is underestimated by the authorities or for which the proposed measures are not parallel to the potential seriousness of this situation."

However, both acknowledge that the American scientific community has responded by conducting very complex experiments as Pérez-Ramírez recounts, "they have experimentally infected lactating cows and other animals in high-security laboratories to obtain answers about the virus's behavior, transmission routes, clinical picture, duration of excretion in milk... which contrasts greatly with the absence of clinical information from farms."

This same community has also warned about this situation on countless occasions: "All major scientific journals (mostly American or American publishers) have released editorials," says Trilla, who recalls with amazement one that directly questioned why there was still no pandemic.

The latest organization to join this warning is the Global Virus Network (GVN), a global and independent scientific organization that signs a paper published these days in The Lancet. They remind that while the current outbreak in North America may be brief, the history of human mortality associated with the H5N1 virus is at least 50% so the current threat should not be underestimated.

What is the current situation?

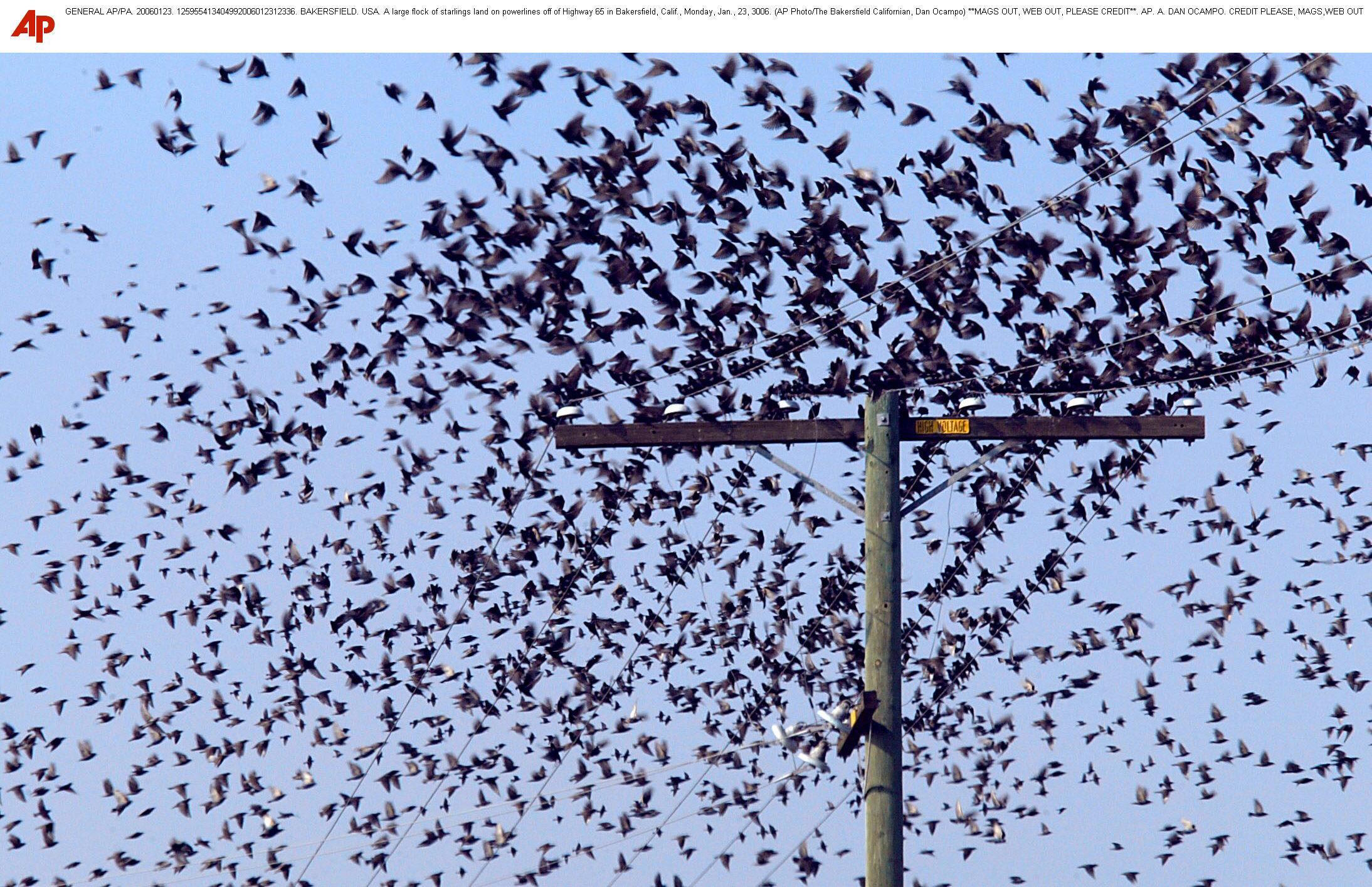

For the first time in many weeks, the numbers have started to decline, but the cumulative total is overwhelming. At the time of writing this report, 168 million poultry have been infected in the United States since the beginning of the outbreak (February 2022), the virus has been detected in over 600 wild and domestic mammals (of 44 different species) as well as in 1032 dairy herds, and the count of human cases is 70, with four severe cases requiring hospitalization and a single death.

We are not talking about an imminent pandemic: the risk to the general population is still considered low, there is no evidence of human-to-human transmission, and it seems that the jump from animal to human is not proving to be an easy task. However, the GVN warns that among the human cases, some are of unknown origin, with no trace of contact with infected animals, leaving room for a possible viral adaptation for efficient human-to-human transmission.

What is certain is that these figures have costs at many levels, and the fact that the virus continues to circulate and has jumped so easily to mammals, especially those with greater interaction with humans like livestock and pets, brings us closer to a much more dangerous situation.

Despite the significant economic and health impact on poultry and dairy farms, the only thing that seems to have truly mobilized the authorities is the price of eggs, which, although starting to normalize, has exceeded eight dollars per dozen (although not yet reflected on supermarket shelves). The scarcity of this cheap and difficult-to-replace protein source (unlike meat) has led to the announcement of a series of measures to quickly address the crisis, perhaps forgetting the context that explains it.

Of the one billion dollars that the government has put on the table to "fight avian flu and lower egg prices," half will be allocated to an undisputed purpose: improving farm biosecurity through audits, technical assistance, and financial support, as well as the commitment to assume 75% of the economic burden it entails. It is estimated that 83% of farm outbreaks are due to transmission from wild birds, so it is a more than justified strategy.

The rest of the funds will be allocated to both increasing compensation for affected farmers (again, something essential to ensure essential collaboration) and indirectly rethinking existing protocols.

It is very likely, but there is also the danger that in order to achieve greater agility or flexibility, some initiatives may be endorsed that could ultimately be counterproductive. We analyze the main proposals:

1. Accelerate restocking and limit the scope of depopulation. When a case of highly pathogenic avian influenza is detected on a US poultry farm, the Department of Agriculture's 'Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Response Plan' is activated, a document known as the 'Red Book'. One of the fundamental measures in this manual is the culling of all birds on the farm.

Epidemiologist Antoni Trilla recalls that this strategy proved effective in 1997 in Hong Kong, during the first outbreak of H5N1 avian flu in poultry with human transmission (there were 18 infections, six fatalities). The then Health Minister Margaret Chan ordered the culling of all poultry in the province (1.5 million) in three days, which ended the outbreak. It was precisely her role in managing this crisis, and later against the SARS epidemic, that endorsed her to be elected as Director-General of the World Health Organization in 2006.

Since then, no one had questioned the basis of the protocol, but the emergence of H5N1 (clade 3.4.4.b) from 2021 showed that this measure did not completely halt the spread of outbreaks, which continued to occur. The truth is that avian flu is highly contagious and lethal for almost all infected birds. There are expert voices that suggest that it may be more compassionate to cull them than to allow a certain death with great suffering (its ravages have been compared to those of Ebola). However, the battery of measures published talks about finding ways to reduce mass culling, and in the new administration, several voices have blamed a "crazy slaughter" (in the words of Elon Musk) for the current egg shortage.

The other leg of that protocol is located in the aftermath, in the tasks of cleaning, disinfection, and quarantine that follow a massive cull and ensure that there is no trace of the virus before reintroducing animals into the facilities, known as 'restocking'. The announcement talks about streamlining the approval process, so it seems more like a bureaucratic issue rather than a relaxation of measures.

2. Eliminate unnecessary regulatory burdens. Bureaucracy again. In this case, it is about addressing a situation that not only slows down the recovery of affected poultry farms but also creates inequalities (reflected in prices) among different states.

However, within this package of measures, the promotion of local or backyard breeding sneaks in, specifically mentioning that "the bureaucratic burdens on independent farmers and on consumers who produce eggs at home will be minimized." They are the so-called 'backyard flocks,' and for many, they have been the hope in the face of a supply shortage like the present, to the extent that even renting a hen has been considered for people to ensure their stock without going through the supermarket.

The issue is that these producers are not exempt from danger, quite the opposite. "Historically, backyard birds have always had a high risk of avian flu outbreaks, both in Europe and Asia," recalls Elisa Pérez-Ramírez, "biosecurity in these cases is practically non-existent, as is the training of owners who are slow to recognize bird symptoms and take appropriate protection and control measures." Two of the 70 recorded human cases so far (one of them, the only death) originate from this type of farming.

3. Vaccinate poultry. This is one of the most controversial points deserving of a thoughtful debate, a debate that may be hindered by the urgent need to lower egg prices. In reality, not even a week had passed since it was announced that this approach would be investigated when Robert F. Kennedy Jr., heading the Department of Health in the new administration, dismissed it because, according to him, experts from different agencies considered it a source of mutations and therefore posed a great risk.

"The thing about avian flu vaccine is that it is similar to the covid one," explains veterinary virologist Elisa Pérez-Ramírez, "it greatly reduces bird illness and death but is not sterilizing." In other words, birds can get infected and continue to excrete small amounts of the virus, leading to silent circulation among seemingly healthy birds. Thus, the virus can continue to circulate 'under the radar', and therefore, mutate. However, this possibility will persist until the virus is eradicated, and none of the other proposed measures promise such an achievement.

"In the absence of a miraculous remedy, vaccination plans are a good alternative," in fact, Pérez-Ramírez considers it essential to realistically consider reducing the number of culls. But the key is that it is not just about vaccinating and moving on; the vaccine is part of a broader... and costly strategy.

"France has been the only European country to massively vaccinate poultry. They took this measure after the devastating 2022 epidemic that resulted in the culling of hundreds of thousands of ducks," recounts the virologist. But they did not stop there, "they spent 100 million euros on a very comprehensive vaccination plan that included vaccinating over 50 million ducks and then continuously monitoring, periodically taking samples from a representative number of birds to confirm that the virus was not circulating." This has led to a significant decrease in the number of outbreaks, but it has also involved a significant financial investment. The state covered 85% of the campaign's cost, a cost that would have been unaffordable for French poultry farmers.

Why was this option then quickly dismissed?

Beyond what has been explained and the fact that in practice it is not an easy or quick measure to implement, the reason seems to clearly lie more in the financial realm than in health. The United States does not import vaccinated birds due to the risk of introducing apparently healthy but infected birds into the country. In fact, when France decided to vaccinate its ducks, the U.S. promptly banned the import of French poultry products. Therefore, if the United States were to start vaccinating, it would have to renegotiate the terms of its trade agreements, most likely not without cost.

Nevertheless, there are significant gaps in this strategy that can only be explained by a short-sighted or limited view of the current scenario. While reconsidering outbreak prevention protocols on poultry farms, they forget that dairy farms, the other major players in this epidemic, do not even have one, and the only initiatives aimed at alleviating this lack are few and late.

While birds have been mass-sacrificed, the same has not happened on cow farms. On one hand, when the virus was detected in cattle, it was found that it had been circulating for about four months, so it had already spread throughout the country due to the interstate movement of infected cows. On the other hand, it is difficult to apply the same protocol to farms with such different operations and animals.

The lack of official measures and guarantees of assistance to compensate for possible costs in dairy farms generated a lack of collaboration with the sector that still keeps us in the dark on many levels: "We lack a lot of basic data on the virus's behavior on farms, such as understanding how the virus jumps from birds to cows, what percentage of cows may be infected but not showing obvious symptoms, or how long the virus excretion lasts in milk," explains the veterinary virologist.

It was not until December of last year that the initiative called 'National Milk Testing Strategy' (NTMS) was launched, based on the analysis of milk tanks on cow farms. This is a very effective measure to detect the virus early on all farms and not just limit it to those that have reported sick cows. However, as warned by the GVN, all measures aimed at surveillance and monitoring of the virus in dairy cows (commercial milk testing, wastewater testing, or testing of farm workers) have been partially and unevenly implemented.

Today we do not know if dairy cows are the only livestock species acting as a reservoir for H5N1, but we do know that they were the origin of most cases of H5N1 B3.13 in poultry farms during 2024, causing the death of over 18 million poultry. This explains the discomfort that Elisa Pérez-Ramírez points out among poultry sector veterinarians, who demand stricter prevention and control measures on cow farms. "The fact that the virus is circulating unchecked in cows not only affects dairy farms but also poultry, egg prices, and overall poultry product prices," she explains.

The genotype D1.1, originating from wild birds, did not really come into play until the end of 2024, and initially was only associated with outbreaks in poultry. However, thanks to the NTMS, in January and February 2025, this genotype was detected in dairy cows in Nevada and Arizona, thus confirming that the virus's jump from wild birds to cows was no longer so exceptional.

Are there only bad news?

To this scenario, some worrying factors are added, such as the entry of the Trump administration. While many of the problems were inherited from the last stage of Biden, the massive layoffs (some are being attempted to rectify) in offices dedicated precisely to the study and surveillance of this outbreak, the lack of transparency, or the announcement of ending collaboration with institutions like the WHO do not invite optimism.

It is also concerning that Robert F. Kennedy Jr has been appointed as head of the Department of Health, a well-known anti-vaccine advocate who has publicly defended the consumption of unpasteurized milk despite confirmed animal infections for this reason. There is even a study pending peer review that shows the virus remains present in cheese made from unpasteurized milk even after 60 days of maturation.

In his recent interventions, he has gone even further and has argued that the remedy to end this virus without resorting to sacrifices is to let it flow, favoring a sort of natural selection. Epidemiologist Antoni Trilla reminds us that this is not a particularly novel idea; during the Black Plague in Europe, there were cities where neighbors or families were locked in their homes and waited to see who survived after 15 days. Setting aside the calamitous nature of the proposal, "the risk is that it flows out of there," Trilla emphasizes. Fortunately, it is not RFK Jr who decides the strategies in this area, but it is still too early to assess the profile of Brooke Rollins, the head of the Department of Agriculture.

The other alarming factor is the increase in cases in pets, specifically in domestic cats (with a mortality rate of up to 90%). This epidemic, the most severe in animal history (and which has spread to the most remote corners of the planet), has caused cases in wild and domestic mammals for some time, but it is worrying that they are increasing among those closer to humans: livestock (recently, the first case of avian flu in a sheep was detected) and pets.

"In the US, there are over 100 confirmed cases of infected cats, and probably many others that have died without being detected," warns Elisa Pérez-Ramírez, pointing out that in felines, mortality rates are very high. A recent study analyzes the infection in two cats that could have been infected through contact with their owners, both of whom work on dairy farms. Recently, data from another study were published indicating a possible transmission in the other direction (from cat to human), but amidst the turmoil of the administration change and the closure of health and research websites, this information disappeared.

In any case, the infection of cats through the consumption of raw milk from infected cows and raw poultry meat contaminated with the virus has been confirmed. Weeks ago, a pet food company prepared with raw meat recalled a batch after detecting the presence of the virus, implying that the meat had passed all controls before and after the slaughterhouse without any issues.

So, what are the good news then?

The most important thing is that the virus has not yet adapted to human-to-human transmission. Each new case is like buying a lottery ticket, so it is impossible to know if it will eventually happen and when. However, although the flu virus is a champion of mutations and recombinations, it is not true that we are just one mutation away, despite the laboratory experiment showing that a single mutation facilitated the virus's entry into mammalian cells. Elisa Pérez-Ramírez along with microbiologist Ignacio López-Goñi explained the real complexity of the necessary mutations occurring simultaneously, in addition to a mutation benefiting the virus in one way could harm it in another.

On the other hand, as Antoni Trilla points out, if that were to happen, "from a human perspective, we would have antivirals that could be used to treat a certain number of cases." The epidemiologist does not trust that we have much immunological memory against H5, but there are resources to develop a vaccine more quickly, since unlike what happened with Covid, the flu virus is an old acquaintance. Both the US and the EU have a stock of vaccines that are not a perfect match for these variants but are a start. However, Pérez-Ramírez reminds us that many of these vaccines are produced in embryonated chicken eggs, creating a vicious circle.

There is an alternative that is no longer unfamiliar to us: mRNA vaccines, much faster to scale and do not require eggs for production. Moderna has one in development, but the Trump administration has withdrawn funding (RFK Jr even said that the covid vaccine was "the most lethal vaccine that had ever existed"), so for now, it is on hold.

With or without vaccines, prevention is key. The Global Virus Network calls for increased surveillance and funding, as well as a commitment to research, collaboration at all levels, and vaccination. And they are not only talking about the United States, just as they are not only talking about poultry: "We cannot focus on some farms forgetting others, just as we cannot care for humans without caring for animals."

We are all part of the same ecosystem and we must make decisions that reflect that idea. Right now, the ball is in the court of the United States, but the truth is that even though there have been no outbreaks of avian flu in poultry in Spain for over two years, their crisis management affects us, to the point that egg prices have also increased in our supermarkets.