The opening scene of The Long Knives (Anagrama), the new novel by the forever author of Trainspotting, is pure Irvine Welsh: the reader witnesses the castration and murder, narrated with the chilling rawness worthy of its author, of a conservative and racist politician. A cruel death that the tormented inspector Ray Lennox must investigate, as he must unravel a dirty network of child corruption involving prominent members of the British upper class while trying to exorcise his many persistent personal demons.

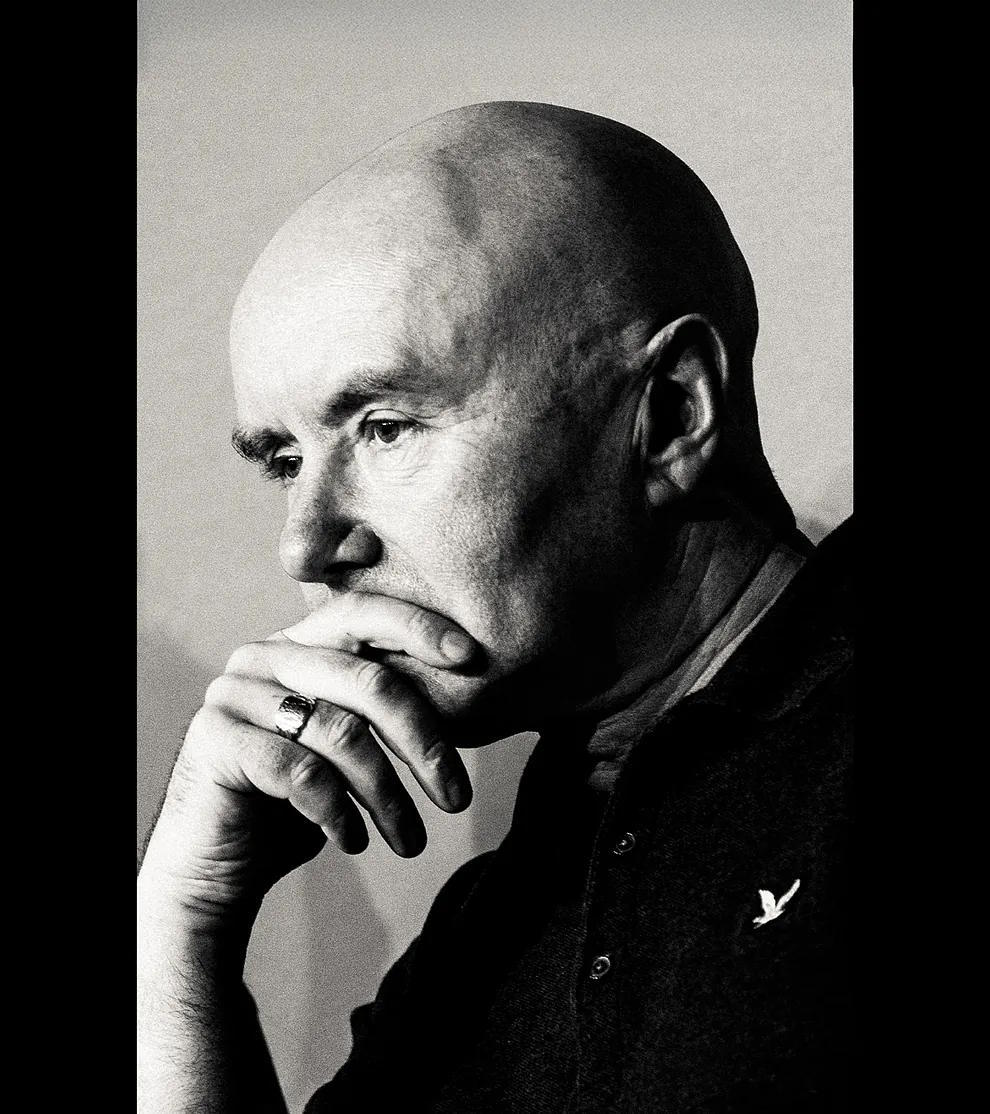

A dark and gloomy sequel to Crime (2008), this work by Welsh (Edinburgh, 1958) is, therefore, a trademark mix of extreme violence, psychological depth, and, why not, a sharp and sardonic humor. "It's true that the beginning is a bit brutal, but humor balances it out," explains the writer with laughter to La Lectura from his home in the Scottish capital. "It is important to use it to give the reader a break and to dissipate the tension. If you force people to read something potentially intolerable, you must give them space to recover. You can show as much darkness as possible as long as, in some way, you grope for the switch. Because life is funny, stupid, and ridiculous, and if we let ourselves go, we become arrogant and start trying to control and manipulate others, so it is necessary to show that relaxed part," he maintains.

Delightfully compulsive reading, The Long Knives is much more than a dark novel with hallucinatory tones: it is a ramshackle and sunny road to hell that leads to the deepest depths of the human soul. "For me, this is an existential thriller about a man trying to accept his own abuse. Genres are for editors and publicists, I don't consider myself a crime writer, or literary fiction, or suspense, or urban literature, or anything like that. I just write and hope that what I do appeals to enough people," he asserts.

Lennox, one of those anti-heroes that Welsh excels at, a distant cousin of Mark Renton from Trainspotting, only wants to atone for all his sins, but to do so, he will have to serve his heart on a platter and forget everything he was to definitively become the man he has always wanted to be. "I see Lennox more as a vigilante than as a policeman. He tries to rid the world of all the abuses he couldn't protect himself from as a child," he opines about the inspector from the Serious Crime Squad.

Translation by Francisco González, Arturo Peral, and Laura Salas. Anagrama. 416 pages. 24.90 Ebook: 12.99

In this sense, the writer delves into that primal feeling of revenge, which he considers "an essential human quality. As a society, we aspire to justice, but as individuals, we only seek revenge. It is interesting because this instinct greatly hinders us as a species, it prevents us from growing and developing, but it is impossible to control," Welsh argues, for whom "the worst thing that can happen to someone is to have suffered abuse as a child. It ruins people's lives. What I try to understand is how one can overcome revenge when something so horrible has happened to you. That is Lennox's dilemma: 'how to overcome this craving for revenge that is killing me? It is something that motivates me, it is my driving force. What am I without it?' These are the existential questions that a character in that situation can face."

"Everything that identified us - capitalism, division of labor, or gender - is crumbling. The life we had is disintegrating around us"

Beyond the plot of child abuse, intertwined with fierce criticisms of the political elite and a fiery defense of transgender identity that sparked much debate in the UK when the book was published in 2022, Welsh asserts that his main motivation was "to raise the idea that we are all confused about what is happening in the world because all the markers that identified us have crumbled and disappeared: capitalism, industrialization, division of labor, sex and gender, identity roles... So we are adrift. The life we had is disintegrating around us," he opines.

A disintegration for which he largely blames technology, which, in his view, "has eliminated the street and community culture of my time. Nowadays, we live in an artificial zoo that we have built for ourselves and have been convinced that we do not need to interact with anyone, express ourselves in any real way, or even leave the house, as we can entertain ourselves, express ourselves, or do anything with a phone. We have forgotten that feeling pain and discomfort is part of humanity, so we try to eliminate it from our lives," he criticizes. "And the blame for this," he asserts, holding up his phone with fury. "Hopefully, if the human race survives, we will see these devices as madness and people who use them with the same surprise as we see people smoking one cigarette after another in the 1950s. Why did those people do that?, we will wonder. I am convinced."

Art and love against technofeudalism

However, the writer, who claims not to want to sound "like an old man prophesying at the bar," believes that what will save us is the inevitable conformity and the human being's yearning for transcendence. "What is clear is that we have not managed to build a society that can activate its best aspects and suppress its worst, the fundamental challenge in which humanity seems to have failed so far. And that is why people are more interested than ever in big ideas, in posing big existential questions about life and death or good and evil, for which technology has a very limited set of answers. So it is that restlessness and curiosity that will save us in the long run," Welsh ventures.

"Political nostalgia arises because people long for the opportunity for social growth, and that cannot be achieved without taxing the rich"

And in that quest for answers, he asserts, "fiction and art remain the most important. The kind of freedom that art offers, where nothing is about exerting power over others, but about trying to find deep and transcendental truths, is becoming increasingly valuable in this technological society where we are programmed to obey instructions," he insists. "Our algorithms tell us to do this, and our governments tell us to do that, to fill out this form, to go to this place and all that. In this terrible situation, I firmly believe that the two forces that can save us are art and love. That's all we have," he defends.

However, what has not changed is his political acrimony towards those elites who concentrate "1% of the wealth, turning capital into something superfluous for the rest of humanity. Without realizing it, those are the people who make us feel nostalgic, a political illness of the worst kind. But people do not feel nostalgic for anything other than a time when the rich paid a lot of taxes, so the State could take care of its citizens. We have moved from a strictly capitalist world to a techno-feudalist world where the elites have increasingly more power and an even greater destructive capacity, as with social media they can divide us and entangle us in sterile controversies like never before," laments Welsh. "It's not about racism or nationalism, but about people longing for social growth, and that cannot be achieved without taxing the rich," he emphasizes.

A necessary debate

One of those major debates, very heated in Scotland, key in the recent elections, and throughout the United Kingdom [where a few weeks ago the Supreme Court issued a ruling stating that the term "woman" in the law refers to biological sex], is everything related to transgender people and gender identity. And Welsh, of course, fully engages in it. "No matter how harmful or divisive it may seem, we cannot continue to suppress things like this, we must discuss something that affects so many people. Besides, for a novelist, it is absolutely fascinating," the writer jests, who even hired an assistant on the subject to write the book. "I thought it would be a form of censorship, but on the contrary, it was very instructive. There are already too many straight white men giving their opinions on everything, I am here to learn."

In his opinion, the radicalisms that have been adopted over the years on this issue are ridiculous, but also dangerous. "We catastrophize everything a lot, select extreme examples, and turn them into a kind of threat when in reality they are not. In fact, it is useful to observe different people who have taken different paths to find the essence of their humanity, as we all want to be the best possible version of ourselves. And some people are adopting very radical and, in a way, very brave paths to achieve it," he reflects. "Today there is no archetypal trans person or trans experience. That is why it is so difficult to represent in literature, but that is, in part, what makes it fun. It is a very small minority, so one must be sensitive, but it is stimulating to launch these debates into society."

Although it will not arrive in Spain for some time, Welsh has already finished the third installment of the Lennox trilogy, published a few months ago in the United Kingdom and significantly titled Resolution. In it, the former inspector has left a police force he no longer believes in and, as Welsh explains, "leads a quiet life and has fun, but only for about twenty pages," he smiles. In this golden retreat, the ex-cop suddenly comes face to face with his former abusers whom he has been searching for years. "He finds them, discovers who they are, and realizes, horrified, that they have been active all this time, without him or the police knowing. So he confronts them and finally exacts his revenge," concludes the writer.