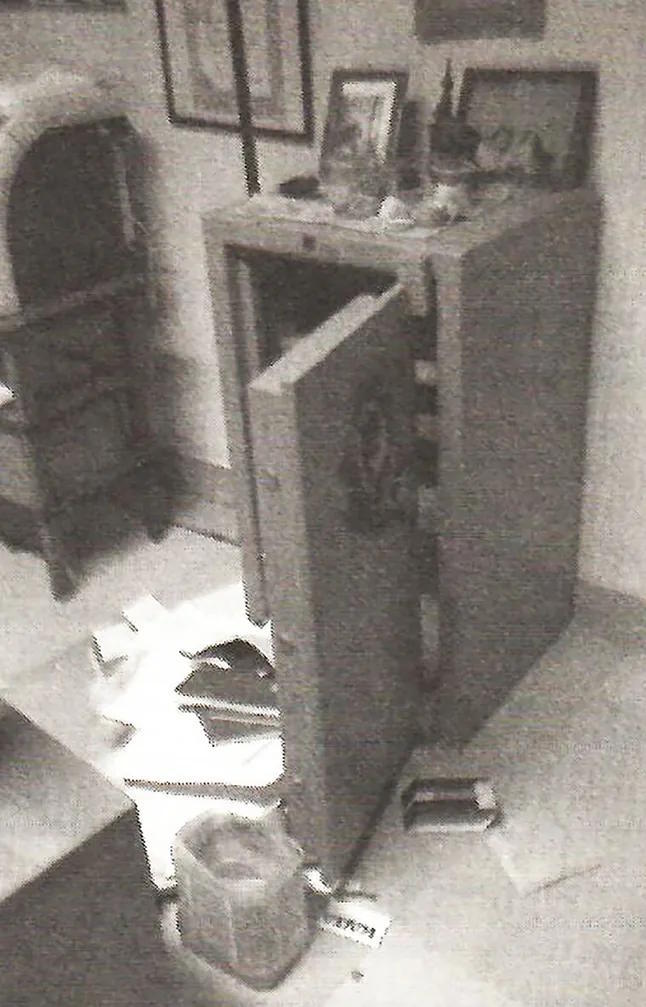

To this day, no one knows for certain what that expertly opened safe contained in the early hours of March 30, 2014, by three highly skilled professional thieves, who, up to this day, remain completely unknown. They managed to bypass all Vatican security measures, blinded the cameras, accurately obtained all the necessary codes, and made sure the guard conveniently fell ill.

The thieves entered the offices of several congregations with blowtorches in hand, grabbed a few euros, and played it cool until they reached their true target: one safe among several, which concealed 22 mysterious folders. Even Pope Leo XIV does not know in detail what happened that night. This does not mean that the contents of those folders, supposedly compromising, could be waiting around the corner, as an inheritance, at any moment, in a place where scandals are managed under the utmost secrecy but not always drowned with absolute efficiency.

According to the most rational Vatican experts, those folders contained the entirety of the COSEA report, the investigation ordered by Pope Francis upon assuming his position to uncover irregularities, concealments in each of the Vatican departments in one of the world's most opaque bureaucracies, and the lack of control over its assets. "That report, of which parts were already extraordinarily scandalous, never saw the light, never leaked. It was secret, and its sole recipient was the Supreme Pontiff," says Vatican expert Eric Frattini, who has just published the book Conclave, detailing many of the information that did leak in one of the most peculiar episodes in Vatican history, where a Spanish priest, Luis Ángel Vallejo Balda, linked to Opus Dei, and his alleged lover, Francesca Chaouqui, were protagonists.

However, as this woman - who, along with Balda, was part of the COSEA group - has written, those folders contained more. They included "the file regarding Emanuela Orlandi (the 15-year-old girl, daughter of a Vatican Prefecture worker, who mysteriously disappeared in 1983, and whose remains have been sought among the tombs of the Holy City even during Pope Francis's papacy); the reports on the political expenses of John Paul II during the Cold War and Solidarity; and the correspondence between banker Michele Sidona and businessman Umberto Ortolani (one, a banker linked to the mafia poisoned in an Italian prison after being extradited by the US, and the other, leading the P-2 Lodge to which Vatican Bank plenipotentiaries belonged in the early eighties)." Whatever was in that safe, the unsolved mystery extends to the times of the current pontiff, who, given the current circumstances of escalating wars and dangerous political delusions worldwide, the internal crisis of the Church, the faithful's disenchantment due to cases of sexual abuse, or the economic situation of the Vatican State, can afford to put his curiosity on hold.

The truth is that the part of the COSEA Report that leaked back then was hair-raising. COSEA was the Commission responsible for the Organization of the Economic Administrative Structure of the Holy See, formed by Francis on July 18, 2013, and led by Maltese economist Joseph Zahra. At the Pope's behest, the Commission's auditors, located near the papal quarters in what came to be known as Area 10 of Santa Marta, requested information on the transparency of expenses, supplier control, real estate contracts, parallel administrations, or financial operations of some dicasteries. Initially, this information was not provided, and later, scarcely and with great difficulty.

Thus, in the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, an institution that demanded 50,000 euros to initiate a canonization process and had over 2,511 open cases, there was not a single receipt, so Pope Francis himself had to inquire about the whereabouts of the 163 million that the Congregation should have been managing. There were bishop families who had taken over the procedures and managed them as a monopoly. In the Peter's Pence, whose goal is also to aid the needy, there were 40 million euros unaccounted for. There was evidence of money laundering and the existence of private accounts that should never have been in the Vatican bank, belonging to clients suspected of using the Vatican to evade taxes. And bishops living like kings in 400-square-meter apartments for which they paid not a single euro. Treasurers who kept money in bags when they saw they were going to be investigated and left holes of 500,000 dollars.

And what about the real estate and artistic heritage. Two silly anecdotes: in the Room of Tears, next to the Sistine Chapel, where popes dress as such once elected, there is a display case with curiosities like a shaving kit or some pope's slippers and liturgical instruments. Among them, a chalice set with precious stones from the saddle that an Arab government gifted to a pope, including the horse that carried it. Access to the chalice was relatively easy. Once audited, it turned out its value exceeded 40 million euros. Conversely, when the value of the highly prized diamond cross of John Paul II was sought, it was found that someone must have taken them because there were barely any replacement crystals left in that symbol.

Pope Francis's purpose of transparency, fighting corruption, and for the humility, which included appointing trusted individuals to head the Secretariat for the Economy of the Holy See (who emptied the powers of the all-powerful Secretariat of State touched by investigations), sparked fierce internal opposition. The theft of the safe was not the only one. The general supervisor he hired, Libero Milone, ended up leaving after his computer was tampered with and after Cardinal Becciu, then Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, orchestrated a campaign against him.

Becciu was eventually convicted of embezzling 100,000 dollars through a non-profit group run by his brother, making a disastrous investment of 400 million dollars in a building in London's upscale Chelsea neighborhood, and paying an unauthorized intermediary a fortune for the ransom of a nun who had not been kidnapped. The Pope's trusted men renegotiated a loan that was at 7.5% and obtained it at 0.7, but still sold the mansion for half of what was paid. Becciu had invested in a network of luxury apartments where, for example, Naomi Campbell stayed, and the trail led to the tax haven of Jersey where the Holy See had no power over anything until 2033; or had invested in the Centaur fund that financed an Elton John movie... What the Pope's trackers found was much more than what has been told. They were careful to detect irregularities but made sure they were not known.

Returning to the beginning, the question of what was actually in that safe remains relevant since those who leaked the partial information to the press, the lovers Balda and Chaouqui, did not need to steal it because they were part of COSEA and had access to much of the data. Whoever stole it did not disclose it. Who was it? Why did they do it then? "They stole them so they wouldn't come out, perhaps some of those mentioned in the reports and interested in absolute silence," says Eric Frattini. Or perhaps because the secrets were different. "I have come to carry the Cross of Christ," said the Pope. Francis knew it well.