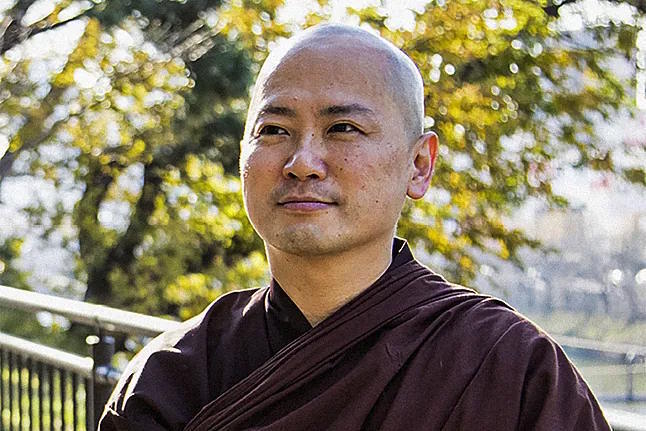

On the other side of the screen appears a Buddhist monk. He appears in front of a Japanese garden background, dressed in the traditional robe and smilingly greeting in Spanish. "Hello! Nice to meet you!". Ryushun Kusanagi (Nara, Japan, 1969) introduces himself with the promise of revealing the keys to happiness that he claims to have found thanks to the wisdom of Buddha. But not without clarifying that, despite getting up every day at four in the morning to write or teach Buddhism, he does not do "typical monk things." "You know, like going to pray..."

First, because Kusanagi is the author of the Japanese bestseller with over 350,000 copies sold: The Art of Not Reacting (published in Spain by Neko Books and the reason he accepted this interview). The book's success is based on unraveling the formula of Buddhism, which is promised to be valid for modern daily life despite its roots in ancient tradition.

Second, because Kusanagi is not here to give us a religion class, but to argue that Buddhism is much more than that. Why not a philosophy of life? In fact, the monk's thesis is this: learn to think like Buddha (not to believe in an almighty God) and you will be happier. Or, in other words, you will be able to take things more calmly.

And third, because this monk avoids euphemisms. "Buddha already knew 2,500 years ago that humans were crazy," he blurts out. Even so, it seems that not all is lost.

But let's start from the beginning. The origin of this story is that of a teenager who one day, frustrated, decides to head to Tokyo. At 16, young Kusanagi had just dropped out of high school. "I had to lie about my age to be able to work and I felt very lonely. I went through a tough time," he recalls when asked about the worst moment of his life, the one that made him suffer like any other human being.

He was not alone. Kusanagi would later graduate from the Faculty of Law at the University of Tokyo. However, his time on campus was not easy either. "I could have chosen another career, but the truth is that I entered university and immediately realized that the only goal pursued was to satisfy one's own pride, to think only of your benefit. It was a great frustration."

Lost in life, some turn to drugs or alcohol. Kusanagi preferred to pack his bags again. The disappointment of university was what convinced him to become a Buddhist monk after a revealing trip to India: "I couldn't find a profession that suited me, and I believed that the right answer to face life would be to become a monk."

At that time, Kusanagi had also not managed to establish the special bond he longed for with his father: "My father was a man who didn't know how to love himself and lacked self-confidence. I sought to have a good father-son relationship but couldn't achieve it. And realizing that it would never be possible was very hard for me."

And now, the first teaching of Buddhism: to live is to suffer. So much so that Buddha's first sermon already addresses what is known as "the eight types of suffering": birth, old age, illness, death, encountering what we do not want, separation from loved ones, not achieving what we desire, and the inevitable human suffering. Everything that harms us fits into a list of eight things.

According to Kusanagi, "the suffering that Buddha speaks of is called dukkha in Sanskrit," a term that comes from the word du, meaning difficulty or obstacle, and kha, which can be understood as eternal emptiness. "It conveys the idea that living is not easy at all," summarizes the monk in his book, to then address "the four noble truths." That is, the four steps on the path to happiness:

Recognize that life involves suffering.

Understand that suffering has a cause.

Realize that it is possible to overcome suffering.

Know the method to eliminate suffering.

Discouraging? In reality, everything is simpler if summarized as... the art of not reacting.

There is an idea that this Japanese monk repeats insistently: "Emotional reaction is the origin of suffering." This means that our mind continuously reacts to all kinds of stimuli, which in turn causes feelings of anger, sadness, distress... Hence, Kusanagi argues that the solution to suffering lies in our mind, that is, in how we face misfortune.

"No matter the problems or sufferings we have to face, all have a solution." According to the monk, "we just need a method," which is nothing more than "how to use our mind." If we manage not to be carried away by passions, we will suffer less. Not reacting to calm the mind. Something like putting on a poker face... but truly feeling it.

Now that the obsession of Silicon Valley gurus with stoicism has brought back interest in the philosophers of Ancient Greece in the West, it is worth asking if deep down we are all talking about the same thing. If stoicism tends more towards pain, in the sense that it is conceived as an opportunity to grow as a person. That is, according to the philosophy of stoicism, pain is not avoided but faced and endured with courage and bravery. Buddhism, on the other hand, is situated between hedonism - the pursuit of pleasure as the ultimate goal - and stoicism. "Right in the middle, in the neutral position," specifies the monk. Because, after all, Buddhism does not avoid pleasure.

Why does it seem then that we have all (or so we say) become a bit stoic? "Because we cannot control our minds," Kusanagi responds. "It's as if we were driving a car that has no brakes or steering, so we are unable to control it. What we want then is to achieve stability, and that's why stoicism attracts us. As soon as the car starts working again, we won't need to go to extremes like stoicism."

Conclusion: we are completely unbalanced. The monk's diagnosis is for a reason. It's not that we are more stressed and anxious than ever - although it may seem so - but that "since the beginning of time, humans have been unable to calm their minds." However, the monk admits that "it is a fact that the world has gone crazy."

- Dictators proliferate in the world. Not only in the United States, Russia, Israel... Monks are not supposed to give specific names, but well. The reality is that there are many people with excessive power who use it to harm others.

According to the monk, it is enough to stop and analyze what drives those who wield power. "If we see where dictators come from, we realize that everything is driven by the desire to accumulate power. The root of all this madness lies in illusions." Buda already knew this 2,500 years ago, Kusanagi insists.

The monk does not hesitate when asked about the great danger that threatens us: "The biggest problem in today's society, especially in the case of young people, is the desire for recognition, the desire for attention."

Buddha already said that, to begin with, desire also leads to suffering. If a desire is fulfilled, we obtain pleasure. But at the same time, this means that if the desire is not fulfilled, we will only have dissatisfaction in return. In his book, Kusanagi explains that dissatisfaction is precisely due to that desire for approval and "wanting to feel validated."

"It is an exclusive desire of humans and seems not to occur among animals," he emphasizes. "Animals also have desires, but they do not have illusions. Animals simply satisfy their needs, eat, sleep, and are already happy. What distinguishes us humans is that we have a brain capable of creating illusions." And that is a problem.

The clearest example, he says, is social media. Is there anything else capable of provoking greater aspirational desire in life? This is how it works according to the monk: "We enter Instagram and immediately see someone we would like to resemble. We want to be like that person. And, by having the illusion of being able to become like them, greed increases. The danger is that we can end up being controlled by illusions."

Another example: the illusion of being eternally young.

- Why are we afraid of aging?

- Because we are precisely controlled by illusions. Because we are not satisfied with our current appearance and want to be more attractive. It is an illusion, and illusion is something that is learned.

- Is getting carried away by illusions always bad?

- No, but if illusions become exaggerated and are not satisfied, they lead to suffering. If you crave a cosmetic surgery that you cannot have, if you want more and more money... you will end up feeling bad.

The monk even warns that having an excess of self-confidence is another trap. People who seem self-assured, he explains, "are actually trapped in the illusion of being incredible or want others to perceive them that way." However, "that confidence is nothing more than an unfounded illusion."

It is important to remember that the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) defines illusion as "a concept, image, or representation without true reality, suggested by the imagination or caused by sensory deception." That is why Buddhism is clear about banishing what we know as positive thinking or positive thinking, so popular in the speeches that spread through social media.

"We are often encouraged to use messages of optimism such as 'I can do it' or 'I am getting better every day'," argues Kusanagi. However, "if that positive message is detached from reality, our mind will perceive it as false and it will cease to be effective." What Buddhism suggests is to "get rid of negative judgments towards oneself and focus solely on the present moment, on what we should or can do."

In other words, words are useless if they are not turned into actions. And if the words turn out to be false - because deep down "I can't do it" - we will have fallen into the deception of illusion. According to Kusanagi, Buddhism "does not resort to words that are not compatible with reality or that, in a certain sense, are illusory".

The monk's teaching is as follows: "We must not get discouraged or sink, nor blame ourselves or look back with bitterness. Let's not be pessimistic. Instead, let's focus on the present, understand correctly and dedicate ourselves completely to thinking about what we can do from now on." Or, as Buddha would say, "rid yourself of the stains of the past and avoid creating new ones. Whoever discovers wisdom frees themselves from preconceived ideas and does not blame themselves." Because "whoever achieves this has already won and there will be no one who can defeat them."