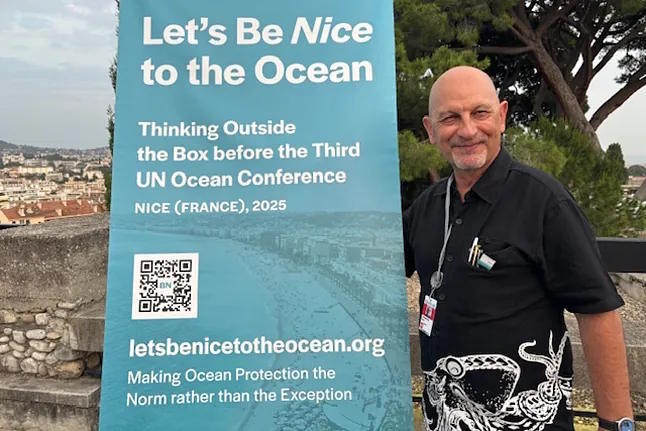

He was a co-founder of Greenpeace, crew member of the Rainbow Warrior, promoter of campaigns in defense of whales and against radioactive waste dumping in the sea, an untamed activist until the recent Oceans Conference in Nice, where he had a very visible role with his campaign Lets be Nice to the Oceans...

It was precisely in Nice where Rémi Parmentier (Paris, 1957-Santa María del Tietar, 2025) granted one of his last interviews to EL MUNDO, thanks to the mediation of Aniol Esteban, director of the Marilles Foundation, who lamented his sudden death from a heart attack: "We have lost another driving force of the environmental-oceanic-climate fight."

With his usual enthusiasm and irrepressible good humor, Parmentier invited us two weeks ago from the emblematic Villa Arson to look at the ocean as "the climate's engine room" and expressed his concern about the storm that is coming our way: "If someone doesn't soon fill the void left by the United States, we are all screwed (and sorry for my French accent homologated by the Cervantes Institute)."

This was Rémi Parmentier, direct and incisive like few others, praised in his farewell by Greenpeace for his "unique style of political judo", settled for years in our lands, from where he recently worked as a consultant for the Varda Group. In the obituary written on the group's website, his friend Paul Hohnen recalled how his birth coincided with the launch of Sputnik, which probably helped shape his legend and character: "There was something Napoleonic about Rémi, not only because of his pride as a Frenchman, but also because of his sense of history and his mission, his vision of constructive confrontation with governments."

Eduardo Jáuregui, who worked with Parmentier on an autobiography (still unpublished), remembers him as "the Forrest Gump of environmentalism, present everywhere: in the zodiacs confronting nuclear dumpers, in protests against the World Trade Organization, at climate summit negotiation tables, at the Vatican (he contributed to writing Pope Francis's encyclical on environmental protection)."

"His great contribution to the movement and to Greenpeace was that environmental NGOs began to infiltrate the halls of power where decisions were made, and that's where he stirred things up," Jáuregui recalls. "Rémi cleverly combined protests and actions that pressured governments with diplomatic negotiation, like when he participated in the International Whaling Commission in 1979, where he managed to negotiate the approval of a moratorium on high seas whale hunting, which accounted for a fifth of the annual hunt."

His activist methods also caused a sensation: from the day he showed up with a plutonium box at an OSPAR meeting (Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) to activating 2,000 alarms on as many clocks at a climate summit in Barcelona, to distributing 10,000 green condoms with the message "Safe Trade" at protests against the WTO in Seattle, where he ended up arrested along with hundreds of activists.

In his "diplomatic" aspect, Rémi Parmentier advised the Spanish government on environmental issues, among others. One of the greatest achievements of his career was the campaign to protect Antarctica, which culminated in the Madrid Protocol (1991). He was also one of the driving forces behind the Global Ocean Commission in 2013, and two years later he established the indispensable link between climate change and the oceans at the COP21 in Paris with the Because the Ocean initiative.

"Let's say that climate change feeds back into oceanic change and vice versa," he acknowledged in his recent interview with EL MUNDO in Nice. "The ocean absorbs 90% of the excess heat we produce and more than 25% of CO2. But all that work comes at an added cost: the ocean is warming and changing its chemical composition. And that changes the currents, with a very significant impact on marine life. Sea levels are rising, and that directly affects coasts and human populations."

His main endeavor, after half a century of activism, was to convince governments of the need to create Ministries of the Oceans, to defend a "comprehensive and ecosystemic" vision against the limited vision of current Fisheries Ministries. Globally, his fight was focused on introducing the "protection principle" for the oceans, beyond the "precautionary principle" in place since the Rio summit. His goal was set for COP30 in Belém in November of this year and at the Fourth Oceans Conference (UNOC4) in 2028, where his absence will be doubly felt. The sea has lost its most audacious agitator.