Dick Tracy got an atom-powered two-way wrist radio in 1946. Marty Cooper never forgot it.

The Chicago boy became a star engineer who ran Motorola's research and development arm when the hometown telecommunications titan was locked in a 1970s corporate battle to invent the portable phone. Cooper rejected AT&T's wager on the car phone, betting that America wanted to feel like Dick Tracy, armed with "a device that was an extension of you, that made you reachable everywhere."

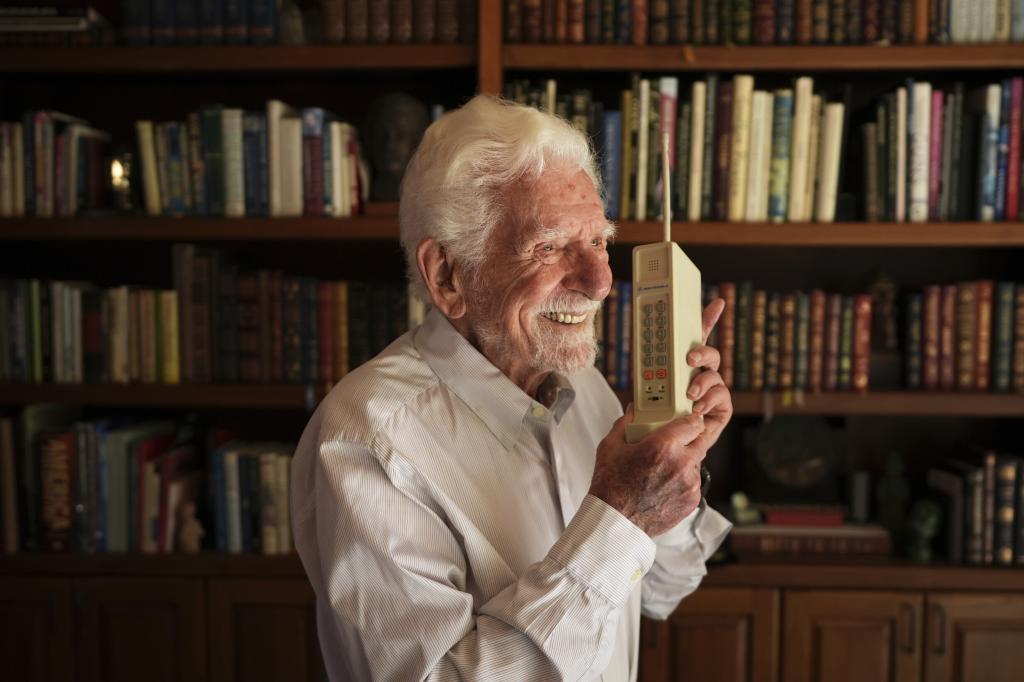

Fifty-two years ago, Cooper declared victory in a call from a Manhattan sidewalk to the head of AT&T's rival program. His four-pound DynaTAC 8000X has evolved into a global population of billions of smartphones weighing mere ounces apiece. Some 4.6 billion people — nearly 60% of the world — have mobile internet, according to a global association of mobile network operators.

The tiny computers that we carry by the billions are becoming massive, interlinked networks of processors that perform trillions of calculations per second - the computing power that artificial intelligence needs. The simple landlines once used to call friends or family have evolved into omnipresent glossy screens that never leave our sight and flood our brain with hours of data daily, deluging us with endless messages, emails, videos and a soundtrack that many play constantly to block the outside world.

From his home in Del Mar, California, the inventor of the mobile phone, now 96, watches all of this. Of one thing Cooper is certain: The revolution has really just begun.

Now, the winner of the 2024 National Medal of Technology and Innovation — the United States' highest honor for technological achievement - is focused on the cellphone's imminent transition to a thinking mobile computer fueled by human calories to avoid dependence on batteries. Our new parts will run constant tests on our bodies and feed our doctors real-time results, Cooper predicts.

Human behavior is already adapting to smartphones, some observers say, using them as tools that allow overwhelmed minds to focus on quality communication.

The phone conversation has become the way to communicate the most intimate of social ties, says Claude Fischer, a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley and author of "America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940."

For almost everyone, the straight up phone call has become an intrusion. Now everything needs to be pre-advised with a message.

"There seems to be a sense that the phone call is for heart-to-heart," Fischer says.

And this from a 20-year-old corroborates that: "The only person I call on a day-to-day basis is my cousin," says Ayesha Iqbal, a psychology student at Suffolk County Community College. "I primarily text everyone else."

When she was a girl, Karen Wilson's family shared a party line with other phone customers outside Buffalo, New York, and had to wait to use the phone if someone else was on. Wilson, 79, shocked her granddaughter by telling her about the party line when the girl got a cellphone as a teenager.

"What did you do if you didn't wait?'" the girl asked. Responded her grandmother: "`You went down to their house and you yelled, 'Hey, Mary, can you come out?'"

Many worry about the changes exerted by our newly interconnected, highly stimulated world.

We increasingly buy online and get products delivered without the possibility of serendipity. There are fewer opportunities to greet a neighbor or store employee and find out something unexpected, to make a friend, to fall in love. People are working more efficiently as they drown.

"There's no barrier to the number of people who can be reaching out to you at the same time and it's just overwhelming," says Kristen Burks, an associate circuit judge in Macon, Missouri.

Most importantly, sociologists, psychologists and teachers say, near-constant phone-driven screen time is cutting into kids' ability to learn and socialize. A growing movement is pushing back against cellphones' intrusion into children's daily lives.

Seven states have signed — and twenty states have introduced — statewide bell-to-bell phone bans in schools. Additional states have moved to prohibit them during teaching time.

The mobile advantage is coming to rich countries faster than poor ones.

Adjusting to life in Russia when Nnaemeka Agbo moved there from Nigeria in 2023 was tough, he says, but one thing kept him going; WhatsApp calls with family.

In a country that has one of the world's highest poverty and hunger levels despite being Africa's top oil producer, Agbo's experience mirrored that of many young people in forced to choose between remaining at home with family and taking a chance at a better life elsewhere.

For many, phone calls blur distance with comfort.

"No matter how busy my schedule is, I must call my people every weekend, even if that's the only call I have to make," Agbo says.

In Africa, where only 37% of the population had internet access in 2023, according to the International Telecommunication Union, regular mobile calls are the only option many have.

Tabane Cissé, who moved from Senegal to Spain in 2023, makes phone calls about investing Spanish earnings at home. Otherwise, it's all texts, or voice notes, with one exception.

His mother doesn't read or write, but when he calls "it's as if I was standing next to her," Cissé says. "It brings back memories — such pleasure."

He couldn't do it without the cell phone. And half a world away, that suits Marty Cooper just fine.

"There are more cell phones in the world today than there are people," Cooper says. "Your life can be made infinitely more efficient just by virtue of being connected with everybody else in the world. But I have to tell you that this is only the beginning."