Self-help is a literary genre that distributes fabulous benefits in the publishing sector and constantly seeks new ways to sell emotional, physical, or even economic well-being pills to the reader. It is not a passing trend: looking back, even in Ancient Egypt there were works called Sebatyt - a word that translates as "instructions" - which referred to teachings focused on the "way of living the truth."

However, due to its chronological ambition, perhaps Emiliano Bruner should be considered a pioneer in self-help, author of The curse of the monkey man (Ed. Crítica), a rigorous essay that addresses the evolutionary roots of the suffering of Homo sapiens. His thesis is that the superpower that helps us process thousands of words and images per minute is also responsible for emotional disorders such as depression or uncontrolled anxiety. His manual accumulates hundreds of thousands of years of experience and, fortunately, also offers solutions to limit its damage.

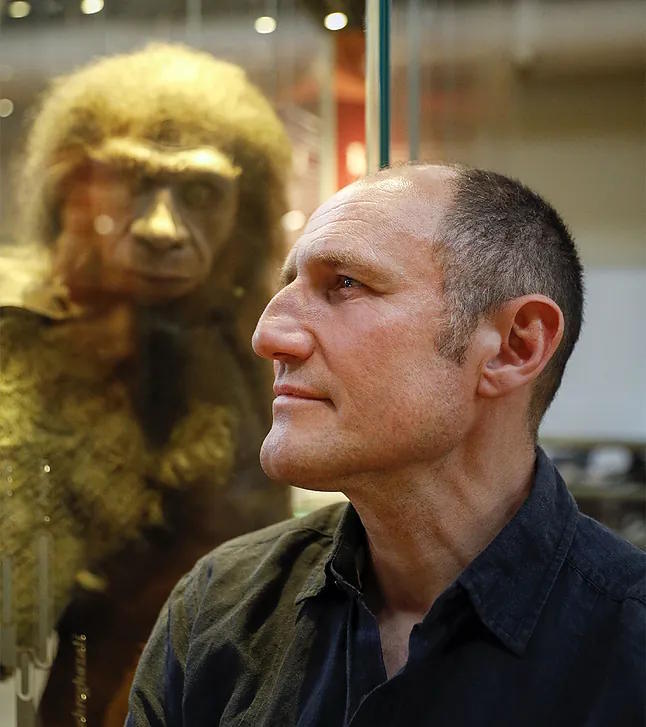

Once the author has been introduced, with whom we strolled on a scorching day through the halls of the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid, where he works as a scientist at the CSIC, we must examine the most important organ in our body. And be prepared to find surprises: "Our brain is three times larger than it should be for a primate of our size. This means that to adjust it, we have to resort to quite strange inventions," says Bruner.

This doctor in Animal Biology from the University La Sapienza in Rome, who works as an affiliated researcher at the Center for Research on Neurological Diseases, is a prestigious paleoneurobiologist: that is, he is dedicated to studying the anatomy of the brains of extinct species. Unable to find a brain from such ancient times, his research is based on investigating cavities and molds of fossils in order to reconstruct the morphology, brain organization, and cognitive functions of our ancestors.

The disproportion between the skull and brain of the Homo sapiens described by Emiliano Bruner is key to an essential characteristic in humans: an unprecedented prodigy in Nature. "It is a superpower that makes us capable of projecting, handling images and words, being specialists in conceptual reasoning. We can imagine an apple even if we don't have one in front of us and we can define it with a word that represents it," he states.

This superpower has given us a great advantage as a species, allowing for tremendous social and technological development. But, as with all interesting fictional superheroes, there is always a dark side. The superpower is also a source of individual suffering.

According to Bruner, the virtual world we create becomes so overwhelming that when it spirals out of control, it turns into anxiety and melancholy. The uncontrolled superpower takes a toll on our mental health and turns us into psychiatry patients. "The human being is an intelligent... and sad monkey," he summarizes.

In these circumstances, the brain generates a rumination of thoughts: a mental wandering that emotionally overwhelms us. This capacity that we all know, to turn things over in our minds like a washing machine on the spin cycle when something worries us, is as human an evolutionary inheritance as our intelligence. It is what could popularly be defined as being obsessed.

"When the moment comes when we can't control this, what I call Radio Sapiens appears, a radio that we are unable to turn off," says the scientist jokingly. "These projections open windows to the past and the future, they become so enormous that they end up consuming the present. You become a slave to the neural network. When it cannot be controlled well, the past turns into anxiety, remorse, sadness. And the future, into uncertainty and fear."

The human capacity to imagine is so powerful that it cannot be stopped at will. "The brain is a Ferrari engine installed inside a Seat 600," explains Bruner. "With this structure, the car can go like a rocket, but probably in the first curve, it will crash because the brakes are not prepared to handle such power."

In his book, Bruner delves into the evolutionary conflict posed by this mental activity that generates distress and anxiety. A phenomenon that, as he analyzes, follows universal patterns. All civilizations make reference to this human curse of thinking too much in an incessant internal monologue. This could be a clue that the anxiety generated by this cerebral superpower has a biological basis. Perhaps it is a kind of chip implanted by evolution itself.

Why could evolution have played this perverse trick on us? To preserve its total mission at all costs: the reproduction of the species. Natural selection is like an Elon Musk with no known limits: it wants us to have children and more children.

Vital anguish, then, would be an immeasurable stimulus for the promotion of reproduction. In a population of hunters and gatherers, impulses and obsessions generate competition. The one with the most resources reproduces more. This pressure generates perpetual dissatisfaction because what has always stressed the sapiens the most is competition.

It must be acknowledged that it is an impeccable strategy of existential suffering in view of the results. The 8 billion humans inhabiting the planet today demonstrate this, an absolute record in the 60 million years of primate history.

"To evolution, our individual well-being is of no importance," says Bruner. "It is often said that evolution favors the strongest or the most intelligent, but it is not true: it only favors those who reproduce more, regardless of whether they are handsome, intelligent, ugly, stupid, tall, or short. Natural selection only values the efficiency of a trait, whether genetic, behavioral, or anatomical, which is the reproductive end. Only the number of children matters, above how they turn out. Evolution does not often select individual traits, but packages of traits. These are reflected in the next generation in a greater number of individuals simply because they have reproduced more."

The big question is whether it is possible to fight for our personal happiness within the evolutionary cage. To express that we want to think without considering the family tree. That not everything revolves around having more Benitezes, Garcias, or Williams. "Many cultures have addressed the issue."

In this regard, Bruner gives advice to redirect our way of thinking and give a touch to the stress of natural selection: everything ends, nothing is forever. "We must not forget that all species become extinct and ours will not be an exception, whether in 50 or 500,000 years, so it is not an end that should question our emotional stability."