"Why is Spain still immersed in corruption?" This is the question posed by the Chinese digital newspaper The Paper, edited by the Shanghai United Media Group, a major media group controlled by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) committee in Shanghai. The article promotes the publication in Mandarin of the book by British historian Paul Preston (A Century of Decline: A Political History of Spain) about corruption as a structural evil that has shaken Spain for a long time.

"At the end of the 19th century, the failure of the Spanish-American War caused Spain to lose its status as a world power. In the following 100 years, Spain experienced monarchic dynasties, the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the short-lived Second Republic, and finally, the arrival of the constitutional monarchy after Franco's long dictatorship. However, regardless of changes in the political system, the Spanish government has always been immersed in corruption and incompetence," reads the beginning of the article in The Paper.

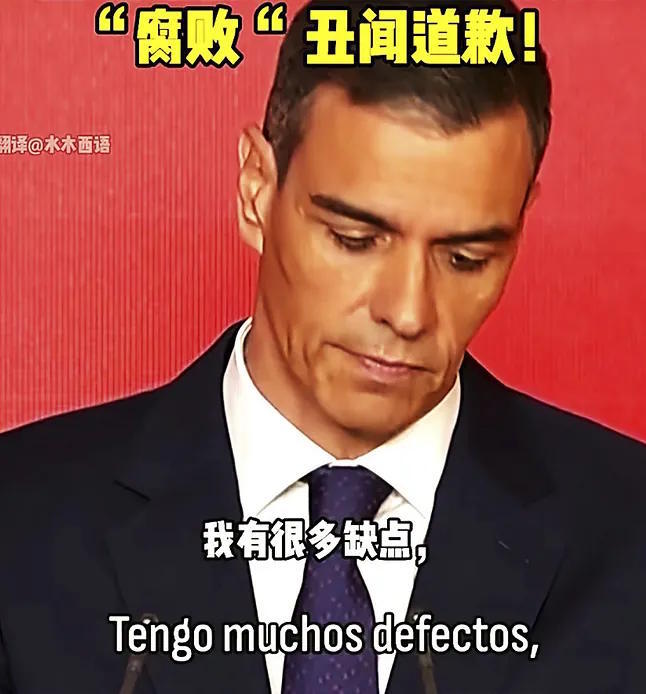

In China, in recent weeks, the corruption scandals shaking the PSOE have not gone unnoticed. On Weibo and Xiaohongshu, two popular social networks, the appearance of President Pedro Sánchez apologizing to the public on June 13 after the report from the Central Operating Unit (UCO) on the former party's Organization Secretary, Santos Cerdán, was shared with subtitles.

In the People's Daily, the official newspaper of the CCP, they have also echoed some episodes of corruption in the Spanish government citing information published in Spanish newspapers like EL MUNDO. "In China, corrupt politicians are sentenced to death and all their assets are confiscated as well," explains a Foreign Ministry official.

Not long ago, in the always censored media and social networks of the Asian giant, videos of the San Fermin festival and other popular celebrations from Spain were the main content. Also, many news about squatters (a phenomenon that amazes and puzzles many Chinese) or football, especially information about Real Madrid and Barcelona. But since Sánchez's approach to Beijing, with three visits in two years to the Chinese capital, plus Spain's growing role as a bridge between China and the European Union, Spanish political news has been shared more intensively on the portals of the second world power.

A few days ago, on a CCTV program, the Chinese state broadcaster, they discussed the "endemic corruption tolerance" in Spanish politics — they also mentioned scandals from other European countries like Lithuania and Slovakia — comparing it with the "firmness" of the anti-corruption campaign led for over a decade by President Xi Jinping and the "exemplary punishments" against corrupt individuals.

A recent case mentioned on the program: the former head of the anti-narcotics brigade of the Police and former advisor to the main political advisory body, Liu Yuejin, was sentenced to death at the end of June for accepting bribes worth over 121 million yuan (around 14 million euros). The death penalty sentence was accompanied by a two-year suspension (the court noted that Liu showed "remorse" and "returned his illicit gains"). According to Chinese law, if the convicted individual does not commit another serious crime within these two years, the penalty would be commuted to life imprisonment.

This same week, for another bribery case involving over 35 million euros, Wang Yong, former vice president of the Tibet Autonomous Region, was also sentenced to death. "Furthermore, he has been deprived of his political rights for life and all his personal assets will be confiscated," states the sentence from a court in the Hunan province, in central China, detailing how Wang took advantage of his position to benefit certain companies in public procurement projects.

Another suspended death sentence two years ago was handed down to a former provincial-level government advisor and CCP chief, Han Yong, who accepted payments of 261 million yuan (32 million euros) over three decades. "He abused his high-profile political position in the provinces of Jilin, Xinjiang, and Shaanxi to illegally assist companies with business operations and project contracting," stated the court's verdict, which also ordered the confiscation of all his assets and properties.

For another bribery case, a high-ranking party official, Zhang Hongli, former vice president of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, was sentenced to death earlier this year. A few weeks before that, an official from the Inner Mongolia region who had been convicted in a massive embezzlement case of over 400 million euros was executed. The former president of the Bank of China, the country's fourth-largest bank, was also sentenced to death (suspended for two years) for a corruption scandal involving over 60 million euros.

China's crackdown on corruption has taken down over five million people in the last decade, including nearly one and a half million officials at all levels. This year, Chinese lawmakers, judges, and prosecutors pledged to impose harsher penalties on representatives of companies and other entities offering bribes or commissions to officials, facing sentences of up to 10 years, an increase from the previous maximum of five years.

China, which retains the death penalty for 46 offenses beyond murder, such as drug trafficking and corruption, executes more people annually than the rest of the world combined. This is indicated in the latest Amnesty International report, but the exact figure is never made public. Executions are considered a state secret. In the Asian country, when the death penalty is imposed by provincial courts (without suspension for later commutation to life imprisonment), the Supreme Court must always review the case before giving approval and setting a date for lethal injection or execution by firing squad.

In recent months, in addition to ordering the intensification of the crusade against corrupt individuals, Xi Jinping has also sponsored an austerity campaign aimed at officials based on eight rules, ranging from avoiding "sumptuous banquets" and "red carpet events" to giving up luxuries that were not frowned upon in the past because they were considered symbols of power. These are some sections of the code of conduct that the Chinese regime promotes to prevent corruption.