Plug-in hybrid cars (PHEVs) have been said to combine the best of both worlds. Powered by a combustion engine and one or more electric motors, they have relatively large rechargeable batteries that, if five years ago barely allowed for 40 kilometers emission-free, now reach double or even over 100 kilometers. By recharging them, they allow for daily use solely on electricity and, on a long trip, no one will suffer from range anxiety like with electric cars. We stop at a gas station and we're ready to go.

This makes them a good option for those who want to pollute less but are not completely convinced by pure electric vehicles. Additionally, in Spain, they have purchase incentives - up to 7,000 euros if the electric range is at least 90 km - and the ZERO label with advantages such as free parking, lower taxes, access to city centers, and high-occupancy lanes.

Sales in Spain and Europe

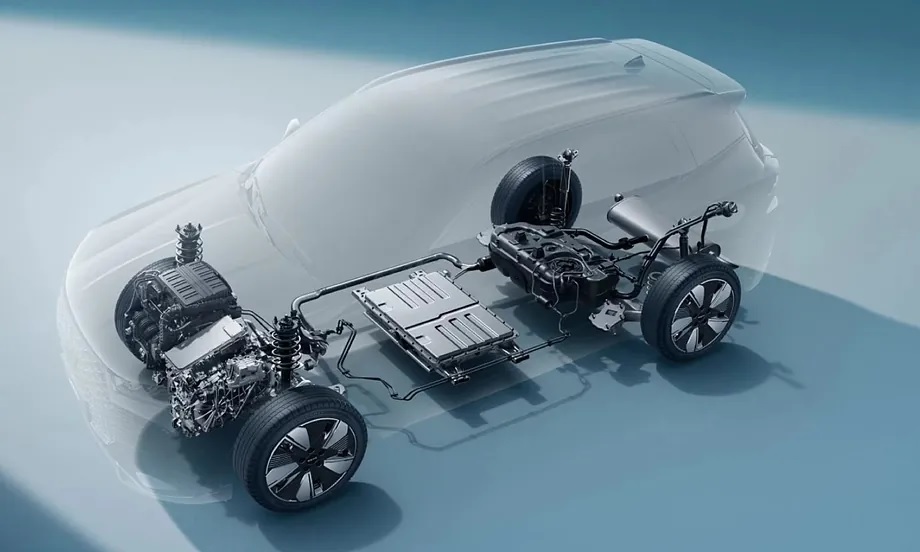

On the other hand, they weigh at least 200 kilograms more than their pure combustion counterparts, may lose a significant portion of trunk space, and are proportionally more expensive. Although not as much anymore, especially due to the influx of new models, particularly from Chinese manufacturers.

As a result, in the first half of 2025, their sales have doubled to 76,295 units, compared to the 61,959 electric cars registered in the same period. The situation is different in the EU, where the share of the latter is almost double (15.6% versus 8.6%). This difference will widen if Brussels does not backtrack on its latest regulations regarding PHEVs.

Because all that glitters is not gold behind vehicles that some environmentalists even label as a scam; and that the European automotive industry wants to keep selling beyond 2035.

Calculation error

However, what the European Commission has done is toughen the measurement of their official consumption and CO2 emissions to align them with real-world figures as variables such as battery recharge frequency influence these, which were not considered in the rigid WLTP protocol introduced in 2018.

The EU soon realized this flaw and took a first step: since 2021, all cars have electronic monitoring of actual consumption. The first large sample analyzed -123,000 plug-in hybrids- yielded clear results. On average, they consumed 3.5 times more than expected: 5.94 liters versus the official 1.69 liters. And mind you, the latter figure could be from an SUV with over 700 HP and 2.5 tons, although many PHEVs are homologated for less than a liter.

Upward differences

The conclusion was not far from what the ICCT (International Council on Clean Transportation) found in 2022 and, a few days ago, Transport & Environment revealed that the discrepancy is increasing. With data from 800,000 cars, the excess in 2023 reached 400% (from 28 grams of CO2 per kilometer to 139) despite the average battery range increasing by 25% in the period.

But, what causes such large discrepancies? It's due to Brussels' own mistake, overestimating the electric mode usage of these cars. This is technically known as the utility factor (UF), which varies for each model and indicates the kilometers driven emission-free compared to the total. For example, for a model with 60 km of electric range, the initial assumption was a UF of over 80%. And for one with 45 km, a UF of 73%.

Less use than expected

The Netherlands already knew this: many users bought these cars for incentives and benefits but then barely recharged them. It's not all negative: they can also be company vehicles that employees receive when they can't recharge them at home. And, although things are improving, recharge speeds were so slow - the initial standard was 3.6 kWh, now reaching 50 or more - that it wasn't worth spending a lot of time to gain a few kilometers back. Unless you were out shopping or at the movies... and there was a charging station nearby.

Much of the above also applies to the Spanish case.

Brands promote

Aware of this and the traffic restrictions in cities, brands like Peugeot installed a blue pilot light that identified when the vehicle was running on electricity. It was eventually removed. BMW, on the other hand, introduced a bonus system for its customers to encourage this use; and today there are cars that recognize Low Emission Zones and turn off the combustion engine whenever the battery allows it.

Because when the battery is depleted, a PHEV can consume a lot, even more than a pure combustion vehicle if only due to the extra weight. However, by recharging frequently, months can go by without visiting the gas station. The person writing this has a small SUV with this technology, and in 70,000 km, the average consumption is barely 2.5 liters.

A smaller UF factor

Therefore, what the European Union has done is reduce the UF, toughen it. To achieve this, it introduced the mandatory Euro 6e-bis standard for new homologations starting this year and, from 2026, to recalculate the figures for each PHEV on sale. Additionally, in 2028, a further revision is planned with the so-called Euro6e-bis FCM.

This would mean that for the model mentioned with a 60 km electric range, the UF would be reduced to 54% with the new standard and to 34% from 2028. This would increase from about 25 grams of CO2 per kilometer to 57.5 grams initially, and to 82.5 grams later.

Such a change in the rules of the game will complicate the CO2 emissions reduction that the industry must face, under the threat of hefty fines. Hence their response: "PHEVs will be crucial to achieving decarbonization goals and engaging consumers in the ecological transformation... But if the EU toughens the utility factor, this could give our competitors a counterproductive advantage," said the letter that the sector sent to the European Commission at the end of August.

When thinking about competitors, one must consider the Chinese and their deployment of plug-in hybrids with very high autonomy. This is one of the strategies that Western brands have left, which implies installing increasingly larger batteries - with its impact on weight - or improving their efficiency. The most drastic option is to stop producing them - giving away that market - and push machinery with electric vehicles whose demand is not what it should be.

Tags and aids in Spain

There is a Spanish-specific aspect: the DGT (Directorate General of Traffic) labels. Its director, Pere Navarro, has stated that he is ready to change them as soon as possible, and PHEVs have been in the eye of the storm for years. The changes introduced by the EU reinforce those who advocate for removing (never retroactively) the ZERO label. And they will also force stricter conditions for public purchase incentives.