Abroad. Almería. Late on a sunny day. Five young people swim in a pond after a hard day's work. They swim carefree, unaware that the water is full of tiny larvae of a strange parasite capable of penetrating their skin and entering their bodies. While they laugh and dive, the infection begins to spread.

Did the scene give you chills? Well, we regret to inform you that what you just read is not part of a horror movie script, but a recreation of a real event. Except for the cinematic licenses, this is how the first documented outbreak of schistosomiasis in Spain occurred, a parasitic disease that until a few years ago only affected countries in the tropical and subtropical areas but has now made its way into Europe.

More than 100 cases reported in Corsica and this first autochthonous transmission in Spain retrospectively described in 2021 indicate that it is "an emerging pathology that needs more attention," as emphasized by Joaquín Salas, a doctor at the Poniente University Hospital in El Ejido, a researcher at the University of Almería, and one of the specialists in Spain who knows this disease "that remains greatly overlooked."

Schistosomiasis is the "second most important human parasitic disease, second only to malaria. But since it has traditionally affected the poorest people in poor countries, it has not received the attention it deserves," laments the specialist.

The numbers of this disease, recognized by the WHO as a neglected disease, speak for themselves. More than 230 million people worldwide are affected by one of the seven main species of the parasite that can infect humans. And each year, these infections cause the death of about 300,000 individuals, according to estimates.

The disease is endemic in 78 countries, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, and is also found in areas of Southeast Asia, the Middle East, or South America. However, in recent years, it has been expanding its range of action due to various factors such as climate change, globalization, migratory movements, or the increase in international tourism.

For the parasite to complete its complex biological cycle and infect humans, a series of circumstances must come together, explains Salas. It is a sort of perfect storm that requires, first of all, that someone already infected excretes parasite eggs into freshwater - rivers, lagoons, pools, ponds, etc. It is also necessary that in that water, there is a specific species of snail that acts as an intermediate host of the parasite and is the only one that allows the infective larvae to develop properly. For the cycle to be completed, it is necessary for a person to immerse themselves in that environment no more than two days after those larvae have been released. "It seems very unlikely that all these circumstances would occur in Europe. But it has already happened. And not just once," hints Salas.

The first alarm in the EU was raised in January 2014 when a 12-year-old German boy suddenly noticed blood in his urine. None of the usual tests performed by the pediatrician could identify the cause of the problem, so the family sought help from the Tropical Medicine Service in Düsseldorf, where they finally solved the mystery. There were eggs of the parasite Schistosoma haematobium, the cause of urogenital schistosomiasis, in both the boy's and his father's urine. Furthermore, his three brothers also tested positive for the pathogen in serological studies conducted later. In contrast, their mother showed no trace of contact with the parasite. None of the family members had ever been to an endemic area of the disease, so the perplexed doctors had to work hard to find the source of the infection. This is recounted in an article published in the journal Eurosurveillance. They finally found the key when, during one of the interviews, the family mentioned that they had spent the previous summer vacation in Corsica, where they had bathed in several rivers. They all remembered the name of the only river where the mother had refused to enter along with the rest: the Cavu River.

"From there, the French authorities began to actively search and found not only that the snail acting as an intermediate host for this pathogen, the Bulinus truncatus, was present in the river but also that there were many more human cases," recalls Salas. In total, over 100 infections were recorded in different parts of the island.

For now, the outbreak in Corsica is exceptional, but the future could be different. As Salas explains, in Mediterranean areas, two key factors for the disease's expansion are present: the existence of the parasite's intermediate host, increasingly well-adapted to a climate where winters are no longer cold, and the presence of affected individuals who can excrete parasite eggs.

It is not only migrants, emphasizes the specialist, but also groups of international tourists, "who, for example, have bathed in the Great Lakes area in Africa and return unaware of the infection."

The infection, which can be severe and lead to, in the case of the urogenital form, bladder cancer, does not always show up quickly and can easily be mistaken for multiple pathologies, clarifies the specialist.

Initially, the affected person may notice a rash in the area where the larvae have penetrated the skin, but this usually disappears spontaneously a few hours later. Additionally, between one and eight weeks after infection, common symptoms such as general discomfort, headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dry cough, etc., may appear. "These are very nonspecific symptoms, so the diagnosis can be challenging," says Salas, who points out that it is the chronic form of the disease, which occurs after repeated exposure to the parasite, that usually leads to more complications.

To understand why this happens, one must know the journey the pathogen takes once it enters the body; a journey that Salas patiently details and whose narrative is hair-raising.

"The larvae are capable of penetrating healthy skin, there is no need to have wounds or injuries for them to enter," he clarifies. They do so without the affected person noticing. They do not feel any pricks or stings warning them of the parasite.

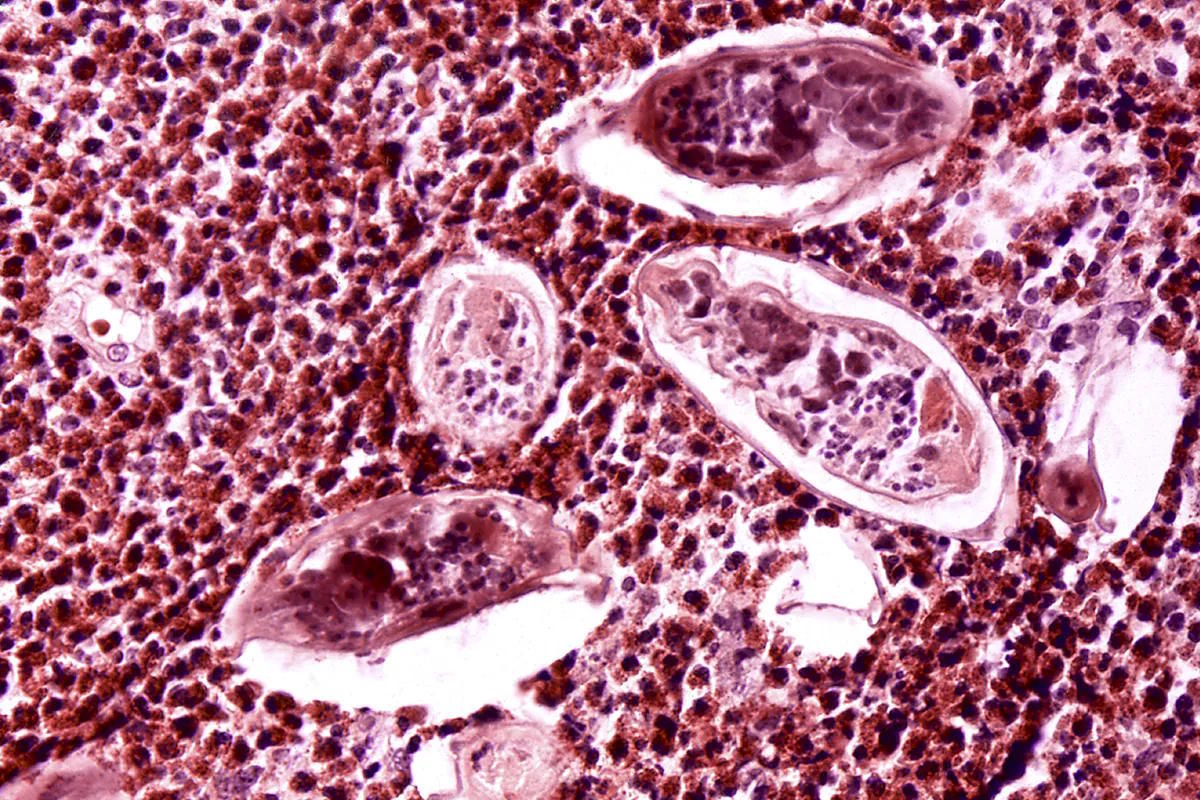

Once inside, these parasites use the bloodstream to move around freely and after passing through a flying goal, such as the lung, they reach the liver where they settle in a network of vessels called the hepatic portal system. It is there where they develop into adults. "They become worms, quite large worms, about 1.5 centimeters in size. They can be seen with the naked eye," explains Salas. "There are males and females that mate and form pairs," he details.

At this point, it is hard not to think of the horror movie again, but the specialist continues with his explanation, and we do not want to lose the thread.

Depending on the type of parasites, the final destination of these pairs varies. In the case of Schistosoma haematobium, the cause of the outbreaks described in Corsica and Almería, the lovebirds migrate to the blood vessels in the pelvis, where the bladder, the end of the ureters, and the genital area are located. There is where they will lay their eggs, which can penetrate the bladder wall and eventually be expelled with the urine to continue perpetuating the cycle.

This constant perforation, along with the retention of multiple eggs in the surrounding tissue, leads to various complications, such as the formation of nodules, fibrosis, edema, and other alterations that can lead to the development of a tumor or problems such as renal failure.

It is also this involvement of the urinary tract that causes the blood in the urine noticed by the German boy who uncovered the Corsica outbreak and many other patients, such as the Almerian farmer who alerted Salas' team to a possible autochthonous transmission in Spain.

Salas vividly remembers the case. "It was a male patient who in 2019 went to the hospital for another issue. His medical history indicated he had suffered from schistosomiasis, an infection associated with a trip to Egypt that the patient had taken. However, when he mentioned that his symptoms had started before that trip, it was decided to review the entire case," recalls Salas, who vividly remembers those days. After much questioning, the patient, originally from Almería, recalled that in 2003, while working in greenhouses in the Poniente area, he used to bathe with four other colleagues in an irrigation pond near the farm.

The researchers immediately thought that could be the key, but they needed to find the other workers to determine if they were also affected. "It was a real detective work," Salas smiles. "They were not in touch, and it took us many months to track them down, but finally, through social networks, we managed to locate all of them," he proudly points out. One of them had also been urinating blood, he confessed. Like in the first patient, a biopsy confirmed the presence of encysted eggs in his bladder. In two other cases, although they had remained completely asymptomatic, serological tests showed positive antibodies against the pathogen.

"Then we asked them to show us the pond, and in collaboration with researchers from the University of Valencia, we found the host snails in the area," he says.

So far, this is the only outbreak of autochthonous transmission recorded in Spain, but Salas' team does not rule out that other cases may have gone unnoticed. "Given that a significant percentage of patients remain asymptomatic or only present mild and nonspecific symptoms, we cannot rule out the existence of cases that have not sought medical attention or whose symptoms have been erroneously attributed to other problems," they state in the journal Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, where they published the details of their work.

"There is a clear risk of schistosomiasis spreading," emphasizes Salas, who advocates for the need to "bring attention back" to the emerging disease. "We need healthcare professionals to be aware of it, to suspect its presence with compatible symptoms, and if they cannot diagnose it, to refer potential cases to facilities where it can be detected and treated."