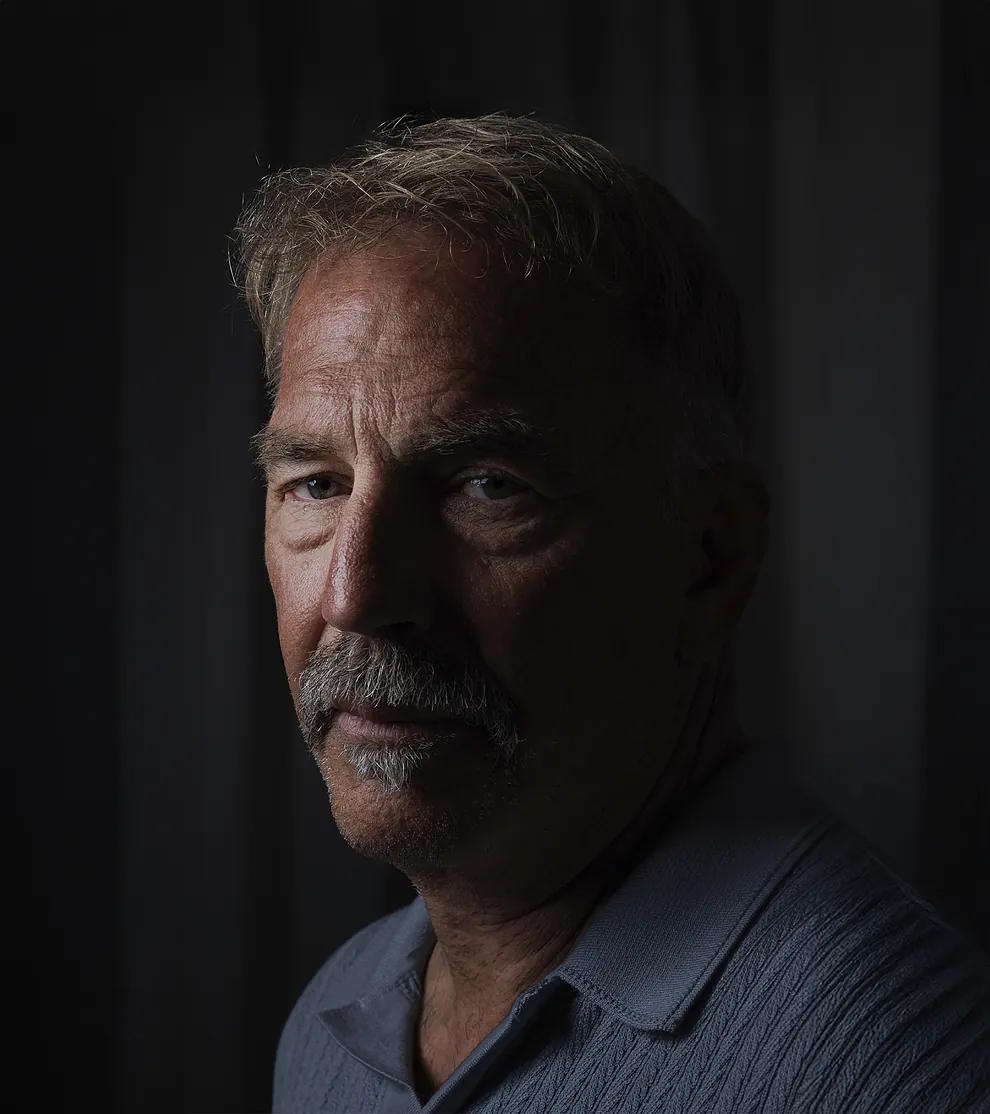

Asking Kevin Costner (70 years old) if he is aware of his obsession with the history of the Wild West is like asking a child if he feels like playing in a ball pit. He is so aware that he pledged all of his children's inheritance to film the movie Horizon (2024), in which he invested 38 out of his $100 million budget. One might think that with this saga, which marked the revival of classic westerns, or with the acclaimed series Yellowstone, the American actor would have had enough of the West for a lifetime. But no: his passion for the Wild West, for its history, and its legends is such that he needed to produce and direct a documentary that would put an end once and for all to the romanticization of that era and underline that a country that forgets its past is doomed to repeat it. To achieve this, he teamed up with historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Pulitzer Prize winner, with whom he conceived The Wild West by Kevin Costner, which premieres on November 3 on the History Channel to celebrate its 25 years.

The star of Dances with Wolves (1990), the movie that triggered his obsession with the Wild West, goes from zero to a hundred when that period is mentioned. His eyes light up, his eyebrows furrow like a university professor, and he repeats the questions to himself, not knowing if it's because he didn't hear them well or because he wants to give the right answer. His priority is to make it clear that the West is not just a place of endless prairies, lone horseback riders, and evil outlaws depicted in some old movies: for Costner, it is synonymous with "blood," "a place more dangerous than we have been told," "wilderness beyond wild," and "a part of history that marked us as a nation."

How much of what we believe we know about the American West comes from movies, myths, or stories told by those who conquered it? That is the question the filmmaker wants to answer in this documentary series. In eight episodes, he offers a new critical look at the origins of the West, challenging the traditional narrative and delving into a complex history that still resonates today. Moving away from the old myths of the lone cowboy or duels at high noon, he invites us to look beyond the legend and explore a reality much more intricate, deeply human, and often darker: the struggle for land. A raw and desperate dispute between indigenous peoples determined to protect their ancestral territories, settlers driven by the promise of progress, and emerging powers that were drawing, in blood and fire, the borders of a new empire.

Each episode presents an essential piece of the mosaic of this shared history: from the battlefields where indigenous confederations faced nascent armies to the fur trade routes, the dusty Oregon Trail, or the chaotic streets of California during the gold rush. Through its protagonists - men and women of flesh and blood, complex, tragic, heroic, and full of contradictions - we discover how conflicts of the past still resonate in the present, and how the foundations of contemporary America were forged in a disputed land inch by inch.

He has made various movies and series where the West was the protagonist. How does this project differ from others?

I like different stories, I am drawn to the West. I can be circling a castle a few times, but eventually, I always want to return to what led us to cross the country and the drama that came with it. I am tormented by what preceded me.

"Personal drama drives me. You can find it in the White House or discover it in a lone ranger."

Perhaps the word "tormented" may impress the reader, but in Costner's mind, the major movements that led to building his country are key to understanding not only the past but also the present. "Personal drama drives me," he asserts. "You can find it in the White House or discover it in a lone ranger." He refers to how "great and dangerous" the United States was at that time. "Those who lived it had to endure and resolve enormous blows to start creating our country and to keep it united," he says. "When you realize that the lone ranger's story only becomes interesting when he meets someone else, like the Native Americans, that's when we realize that's where the drama lies."

Why do we like Western stories so much?People like them because they actually happened. When you see images of those Americans, the image that forms in your mind is that of a solitary person on horseback. There is something terribly romantic about that idea. You put him against a beautiful landscape and it can leave you breathless, but you must remember that this man on horseback didn't know where he was going, what he was going to experience, what he was going to find. The U.S. was simply that: an unknown country.Was the West a place that could become a home for anyone?Why did people go West? The East Coast, New York or Boston had no space. And then they were promised that in the West, they could have their land, and that promise was there for 400 years. Is that promise still alive? I would like to think so, but we are forgetting what we were, what allowed us to expand. If we look back, we can see how we became great. We need a broader view of ourselves, to empathize, to understand that this doesn't begin or end with us. We are part of a continuum.

For Costner, the image that the film industry has created of the Old West responds to the fact that "we just wanted to keep seeing the beauty of America." "We didn't see the exploration, the confrontation, which ended in blood," he says. "People didn't want to see that: not the fear, not the massacre, not everything that comes with a clash of cultures... When we look within, we realize it wasn't easy and that there were people like us who had to react to being in a harsh place where they had to live by their own rules and protect their family."

"We are obligated to teach our children the history of our country, the struggle of their grandparents, the struggle of the country itself."

Because that "promise" of land for all led to expelling those who were there: "We were going to expel the people we were cornering so they would leave us alone. We were a country in the making. World preeminence, where we set ourselves apart from other countries, we have achieved in the last hundred years. And the reason we could do it was thanks to the convergence of all those people coming from other parts of the world."

Is diversity important?

There was a shared intellectual process, an intellectual curiosity. The last hundred years were the product of the different combination of people and cultures. We are excellent and we grew at an incredible rate to achieve the global status we have now thanks to diversity.

To what extent has he managed to instill his passion for the West in his children?

It's a great question. You want your children to listen to you, but they prefer to listen to others. So, it's surprising when they tell you later, "I love your stories." We are obligated to teach our children the history of our country, the struggle of their grandparents, the struggle of the country itself, and perhaps even more importantly to ask them: Where do you think we are going as a country now? Where are we going as a world? We have the ability to teach without lecturing, without forcing something into our heads. The history of our world is glorious, it's tragic, there are inevitable moments. We should have a poetic sense of how we can improve ourselves.

We want to continue talking with Costner precisely about that 'where are we going?' but the actor interrupts us with a resounding "I want this to be known to everyone." "About what?" we ask surprised. "There are too many Math classes in school, so we need more History, because those who are good at Math will always be. But what do we really need? More History."

The next question is almost obligatory: Is it necessary to know the origins of the U.S. to understand the present or is it necessary to go back to the past to avoid repeating the same mistakes? "History is so important... Everyone wants to know, wants to see. Why do we go on vacation to one place and not another? And what happens when the place we go to marks us? There is a moment when we want to return to it. We return because something affected us, and not just the pure beauty of a land. We could return through a movie or a documentary and it would move us the same because men and women are not so different in any century. We should be excited about our own history. Yes, I care about it, and yes, I hope we can do better."

And what can the younger generations learn from observing the history of the West?

What they will see is the truth. I can't predict which young people will see it, I can only predict that when they do, they will find a level of truth and humanity. This is what happens in the formation of a country and, whatever country they come from, it happened in their country and is no different from the rest of the world. Let's dispel the myth that what happened in the Old West was like landing in Disneyland (...) What happened is real. So real that it marked us as a nation. The real history of the United States is the history of immigrants. The glory of the United States, its wonder.