On October 31, 2019, Mario Draghi left his position as President of the European Central Bank. He did so in an event where Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, and his friend Sergio Mattarella spoke. The three, leaders of the major European powers, bowed their heads to an economist, a technician, who came as a senior official and left as a legend, with the eternal and unsurpassable epithet of "savior of the euro." That day, they already elevated him to the pantheon of the Union, placing him alongside Monnet, Schuman, and Spinelli for his vision, or Adenauer and De Gasperi for his determination. "A few weeks ago, you evoked the three characteristics of a good public servant: knowledge, courage, and humility. Dear Mario, you honor and have embodied all three," they said to him.

Draghi belongs to that purely Italian lineage of technocrats with more political savvy, cunning, agility, and ambition than most professionals in a parliament. Profiles that spend their whole lives in the background but do not hesitate for a second when the call of Syracuse comes, whether to save the national bank, the euro, or their country.

Today his career is admired, almost revered. From an orphan who took care of his siblings at the age of 16 to a disciple of Modigliani, Solow, and Fischer at MIT, a professor, Treasury official, director at the World Bank, employee at Goldman Sachs, governor of the Italian Central Bank, the ECB, and prime minister. Someone with power and authority, capable of transcending the boundaries of the collective imagination, to become a mythical, almost mystical figure.

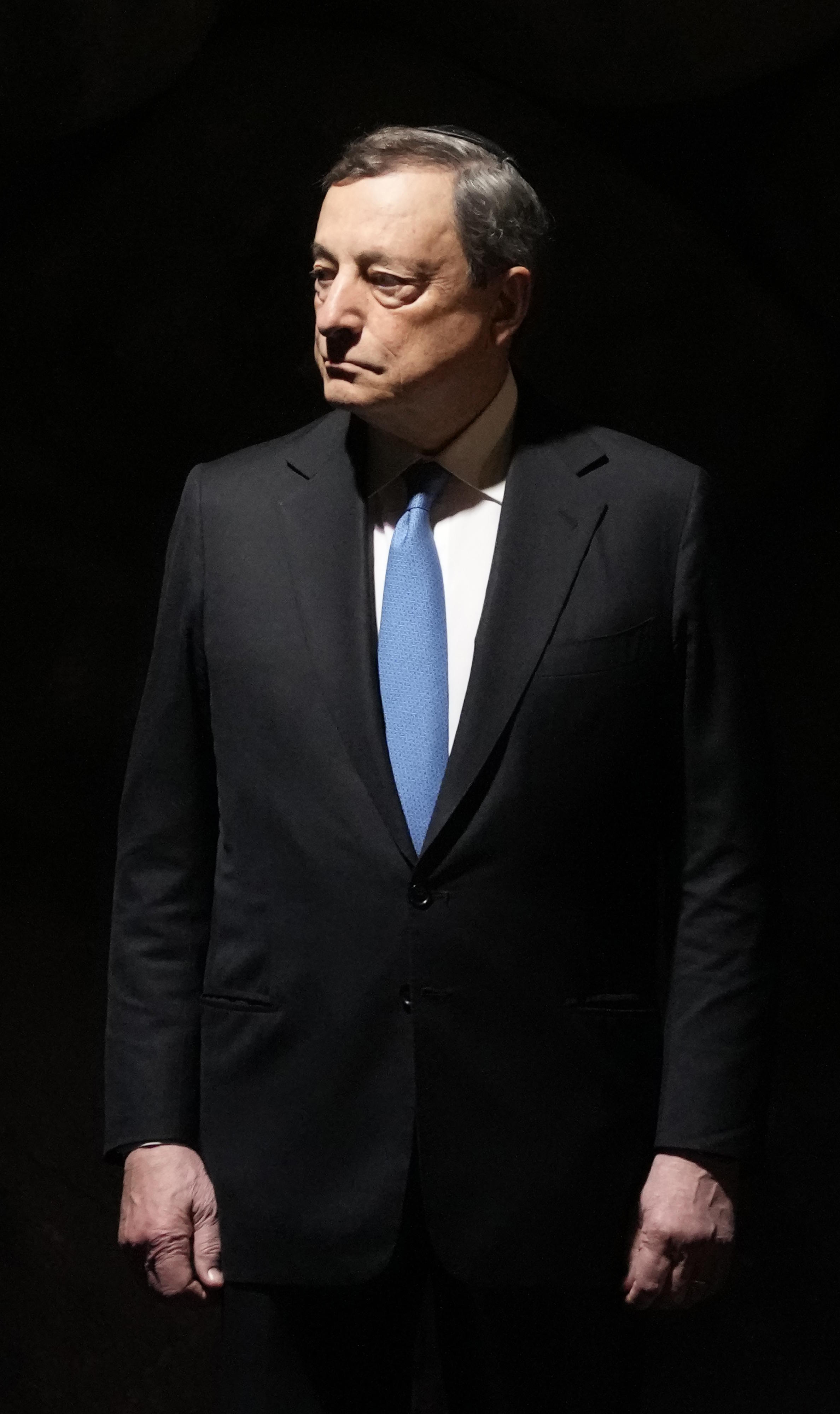

Draghi is an outstanding economist, analytical, with a long-term perspective and a short fuse. Someone with a brutal sense of responsibility, who never ran for election but accumulated more power than most presidents, even before leading Italy for 20 difficult months. He is often described as "cold," serious, very "Jesuit," with wit and humor in private and none in public. Extraordinarily reserved and discreet, driven by reason and numbers, light-years away from the passions and identity-driven sense that marks our era. But with a direct and aggressive style, few qualms, and even less patience for nonsense.

A European, tireless advocate for greater integration, he was baptized by two of his biographers as "The Architect," for his skills, his dexterity, but also because "he has the art to get what he wants." His life is full of successes and recognitions, but with a deep-seated fear. To be remembered not as the great critical conscience of the continent, but as a Cassandra of the 21st century, capable of anticipating, dissecting, and warning of the great existential dangers, both for the EU and the world economy or democracies, but doomed to be ignored time and time again. Applauded, praised, quoted, and awarded, but ignored. In his requests from Frankfurt, in his reforms from Rome, in his reports for Brussels, in his speeches from Oviedo.