The disgraced politician sits, hands on knees, eyes downcast, voice measured. In the background, a blurred prison hallway. In front, an unrelenting camera. "I betrayed the Party's trust," confesses Tang Yijun, former Minister of Justice of China, detailing bribes, favors, and bought silences over the years. "I am truly ashamed and have nowhere to hide," he concludes.

The Chinese state television, CCTV, has been occupying prime time slots for days, both at noon and at night, with one of its most reliable formats: public confessions. In an almost hypnotic loop, officials, politicians, bankers, entrepreneurs, and military personnel already convicted of corruption stand in front of a camera to dissect their crimes with carefully rehearsed frankness. There are no interviews, just a monologue of guilt that turns prime time into a showcase of exemplary repentance.

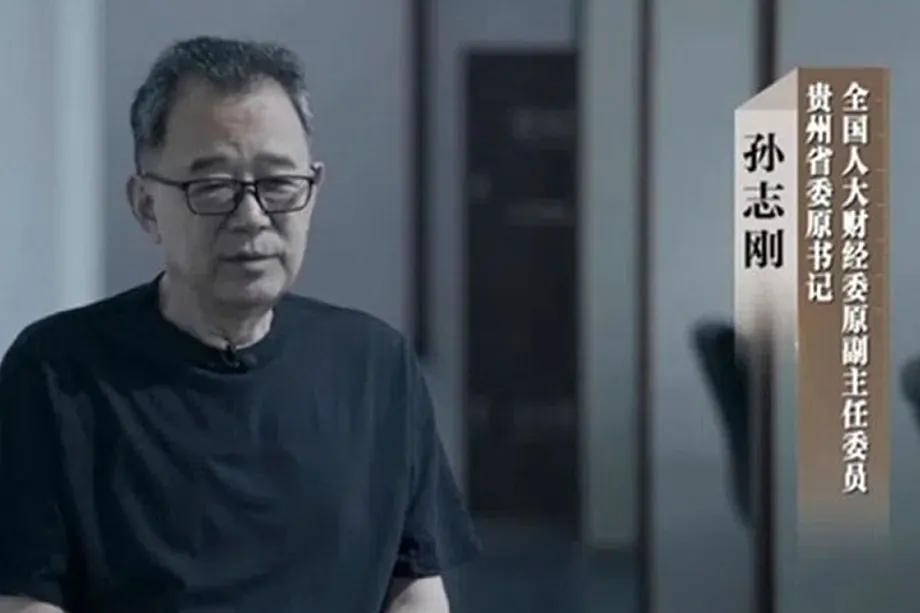

"I crossed the line and committed serious crimes," admits Sun Zhigang, former Communist Party (CCP) secretary in Guizhou province, who was sentenced to death in 2024 for accepting bribes totaling over 813 million yuan (around 100 million euros). "I became a corrupt official, a swindler, and now I have fallen into absolute disgrace," says Wang Yilin, former president of China National Petroleum, a state-owned oil company.

Before the broadcast begins, a warning on the screen sets the moral framework of the show: what follows are real stories of high-ranking officials fallen from grace, transformed into instructive examples of what happens when one crosses the red line of absolute loyalty and obedience to the CCP. From there, the confessions unfold in carefully dosed chapters: forced tales of guilt and repentance that seek to organize the facts in a televised ritual where entertainment, political pedagogy, public chastisement, and propaganda blend together.

"I DESTROYED THE POLITICAL ECOSYSTEM"

In one of the chapters, the protagonist is Fu Zhenghua, former Deputy Minister of Public Security and former anti-corruption "czar." Seated, he admits to turning his power into a network of personal favors: rigged promotions, protection for close businessmen, bought silences. "I destroyed the political ecosystem," he confesses, as if reciting a learned lesson, before asking for forgiveness from the Party and the Chinese people.

Li Xianlin, another corrupt former member of the Chinese Communist Party, during his forced confession.

The format repeats with almost mechanical precision. First, the moral downfall: the moment one admits to having "lost their way." Then, the inventory of crimes, narrated with bureaucratic coldness. And lastly, the ideological surrender. Zhou Jiangyong, former Deputy Mayor of Hangzhou, acknowledges allowing his family to "interfere in power," a common euphemism for the enrichment of wives and children in the shadow of the position. "I did not resist the temptation," he says, before accepting that his punishment is "fair and necessary."

Among the faces paraded on the screen is Lai Xiaomin, former president of Huarong, one of the largest state-owned asset managers in the country. In his confession, recorded before his execution, he admits to accepting bribes "without limits or shame." The camera details the amounts he embezzled (almost 1.8 billion yuan, around 220 million euros at the exchange rate) and additional sins: bigamy, abuse of power, and a life of luxury incompatible with public service. "I thought money could buy everything," he admits. "I should never have misappropriated this pension fund," also acknowledges Yang Sujiao, former senior Social Security official.

In another episode, Ren Zhiqiang, a real estate tycoon and former bigwig of the CCP, known for his critical tone towards the leadership, appears. In his case, the confession shifts from bribery to political discipline. He admits to making "inappropriate comments." The self-criticism goes beyond the criminal: "I ideologically deviated from the Party," he points out, emphasizing that corruption, for the regime, does not only have to be economic but also doctrinal.

7.2 MILLION CORRUPT OFFICIALS

Chinese President Xi Jinping has ordered the intensification of the country's largest anti-corruption campaign in recent months. In 2025, according to the latest official data, the CCP punished a record 983,000 officials, a 10.6% increase from the previous year. This is the highest annual figure since these data have been published, a couple of decades ago. Sanctions range from reprimands and demotions to Party expulsions and detentions. Since Xi came to power in 2012, over 7.2 million officials at all levels have been purged in the anti-corruption campaign.

Zhou Xiaojian, former director of the Housing Repair Fund Services Office in Dongan County, Hunan Province, during his televised confession.E.M.

"Corruption is the greatest obstacle to the party and the nation's progress," proclaimed Xi in mid-January before the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the feared internal organ of the CCP responsible for cleansing corrupt officials. "This year, discipline must ensure that the decisions of the leadership are implemented firmly and without deviations," warned the supreme leader.

In recent days, corruption purges have also been in the spotlight in state media due to the fall of one of the seemingly untouchable military figures: the powerful general Zhang Youxia, who was the Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest leadership body of the Chinese army, chaired by the omnipresent Xi. His abrupt dismissal—and the officially announced investigation for "serious violations of discipline and law"—has surprised both inside and outside China. Zhang not only held one of the highest military positions but was also considered for years a close ally of Xi, with personal and family ties dating back to previous generations of Communist leaders.

The Chinese military has been one of the main targets of the anti-corruption campaign since 2023. At least 60 senior military officers, two former Defense Ministers, and executives from the defense industry have been investigated and removed from public office. Many of them were later sentenced to prison. Some also appeared on the televised confession show.

Gu Junshan, former lieutenant general and head of the Logistics Department of the People's Liberation Army (PLA), sits with a stiff back and restrained expression. He talks about military warehouses turned into private businesses, inflated contracts, and a bribery system that thrived under the protection of rank. "I used the army's resources as if they were mine," he admits, before acknowledging that his personal ambition "eroded the purity of the armed forces."

Another case, that of Xu Caihou, former Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission and one of the highest-ranking officers purged in decades, is reconstructed through archive footage and snippets of his confession. The narrator recalls how he turned promotions into commodities and loyalty into transactions. "I sold positions and bought silence," he admits in a testimony recorded during the disciplinary investigation. The camera emphasizes the gravity of the offense: not just economic corruption but the breach of the fundamental principle of absolute obedience to the Party within the military. At another point, the series addresses the downfall of Guo Boxiong, who was also Vice Chairman of the CMC. His confession emphasizes political betrayal. "I lost ideological control," he states.

FROM EVERTON TO JAIL, VIA THE CHINESE NATIONAL TEAM

Another recently aired episode, titled Correcting Misconduct and Serving the People, focuses mainly on explaining how disciplinary and supervisory bodies have continuously intensified their efforts to investigate and punish corruption. It delves into how the purgers worked on highly publicized cases like that of former footballer Li Tie, former Everton player and national team coach. Investigators uncovered that Li paid bribes worth millions of yuan to secure his position as national team coach and participated in match-fixing during his years managing clubs in the Chinese Super League. "At that time, certain practices were common in football, but that does not excuse my actions," he stated in his televised confession.

Within the financial system, one of the most popular confessions is that of Tian Huiyu, former president of China Merchants Bank, who admits on camera to facilitating irregular loans and using the state banking system as a platform for private networks of enrichment. "I treated the bank as if it were mine," he says. From the judicial apparatus emerges a former head of several provincial Prosecutors' Offices, Zhang Jianqiu, who acknowledges having interfered in investigations and sentences. "The judiciary lost its impartiality under my decisions," he admits.

In the police field, one chapter focuses on the case of Sun Lijun, former Vice Minister of Public Security, who explains that, beyond accepting bribes, his main offense was "excessive political ambition." The same ambition that Su Shulin, former governor of Fujian province and former high-ranking official of the Sinopec oil company, had. "I lost the sense of discipline," he repeats. With a subdued voice, Bai Enpei, former Party Secretary in the regions of Yunnan and Guizhou, admits to accepting bribes for decades. "I thought no one would dare to investigate me," he acknowledges.

All programs share a very intense introduction music, like the one accompanying chases in action movies. The soundtrack directs the narrative, setting the tempo of a televised liturgy that begins with images generated by Artificial Intelligence. These show mountains of gold coins and men in suits exchanging briefcases. Corruption is narrated with suspense. It is the televised spectacle of guilt and public humiliation.