At the eastern end of the Taklamakan Desert, where the map turns ochre and the horizon dissolves into dust, Lop Nor ceased to be a salt lake and a footnote on the Silk Road to become, in the 1960s, a key piece of China's atomic ambition. Since then, it was literally erased from ordinary maps and encapsulated under the logic of military secrecy. Its guarded perimeter - hundreds of kilometers of arid plains, barely perceptible landing strips from satellites, and underground galleries - overlaps with a territory that also holds archaeological sites of ancient caravans that crossed this inhospitable corridor of Central Asia for centuries.

For decades, the Chinese press barely mentioned this place, and accounts from scientists or soldiers stationed there were censored. Sandstorms erase tracks within hours, and the landscape, shrouded in a nearly permanent yellowish haze, has consolidated an aura of mystery around a scenario that remains synonymous with nuclear test site and one of the most secretive chapters of contemporary China.

Lop Nor is now back in the spotlight. Earlier this month, US officials hinted that Chinese scientists may have conducted secret nuclear tests in this desert enclave. This week, a senior State Department official presented new seismic records to support the accusation: according to Washington, in June 2020, Beijing allegedly conducted a "low-yield nuclear test" there, carefully designed to go unnoticed.

It was in Lop Nor where China detonated its first atomic bomb in 1964, breaking into the nuclear club during the Cold War, and where just 32 months later it tested its first hydrogen bomb, in a rapid race to catch up with the United States and the Soviet Union. Between 1964 and 1996, the Asian country conducted 45 nuclear tests in the area before joining the international moratorium associated with the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which has since set the limit of what is allowed.

For years, US analysts have argued that if China were conducting prohibited tests, they would not resemble the spectacular explosions of the Cold War but rather much more discreet operations. The most cited hypothesis is that of detonations in underground cavities. The idea is relatively simple: by detonating the device in a large underground chamber, the shockwave loses some of its energy as it expands in that empty space before transmitting to the surrounding rock, reducing the seismic signal recorded by monitoring stations thousands of kilometers away.

If one imagines how these complexes would be, they would not be so much like movie-style bunkers but rather a network of galleries and deep wells drilled into stable geological formations. In places like Lop Nor, the desert subsurface and the remoteness from large population centers offer optimal conditions. Access points, according to some international observers, could consist of horizontal tunnels reinforced with concrete and steel, where technical teams would install sensors, wiring, and sealing systems designed to contain the pressure and gases after the detonation. After a test, these galleries are usually rendered unusable or sealed, becoming invisible scars under the sand.

During the Cold War, both the United States at the Nevada Test Site and the Soviet Union at Semipalatinsk explored methods to contain or reduce the signal of certain underground nuclear tests. The architecture of these places, as described in technical reports, usually prioritizes compartmentalization and redundancy: armored doors, intermediate chambers, and long tunnel sections that act as additional buffers. Externally, the visible infrastructure (for foreign satellites) is minimal, with some surface facilities, communication antennas, landing strips, and roads disappearing into the dunes.

The challenge for international verification systems is that, at very low energy scales, distinguishing between a small explosion, an underground collapse, or even certain mining activities can be very complicated. But according to Washington, a monitoring station in Kazakhstan recorded a magnitude 2.75 event on June 22, 2020, in the vicinity of Lop Nor. Christopher Yeaw, US Deputy Secretary of State, stated on Tuesday that his administration "is aware that China conducted a nuclear explosion that day."

Chinese government spokespersons deny conducting nuclear tests in recent years, arguing that the Asian superpower respects the international moratorium associated with the CTBT. Although this treaty never entered into force, Beijing and Washington maintain that they comply with its provisions 'de facto'.

The treaty prohibits any nuclear explosion with energy yield but allows experiments with fissile material that do not produce a strong nuclear reaction. Experts point out that this dividing line is very fine and, above all, difficult to verify when it comes to small explosions.

Beijing also maintains that its nuclear strategy is guided by the so-called "no first use" policy, a principle committing not to use nuclear weapons except in response to a similar attack. This doctrine is reiterated in its Defense White Papers, where the Chinese government states that it will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear powers and that its goal is to maintain only the minimum level of capabilities necessary to ensure national security.

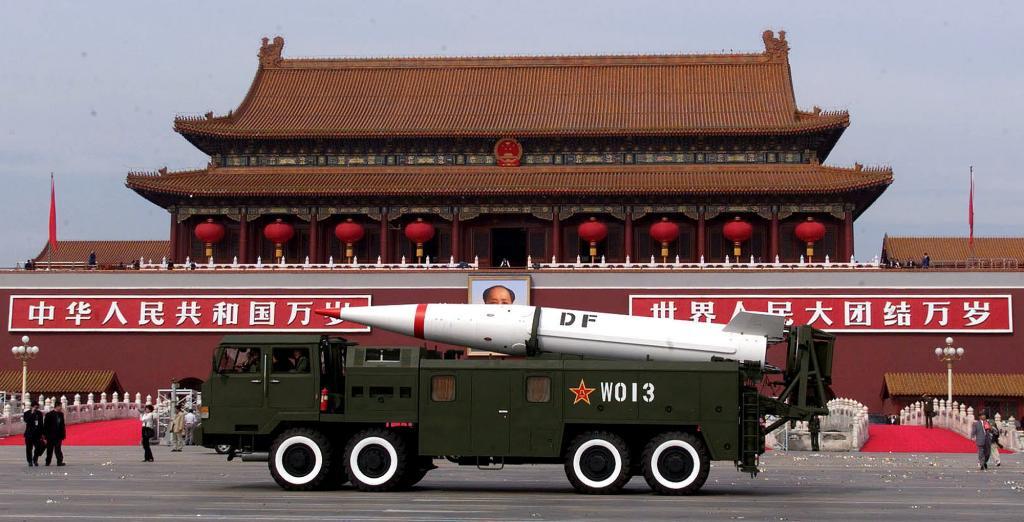

However, the numbers reflect a rapid modernization of its nuclear arsenal. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China had around 600 nuclear warheads in 2024, still far behind the arsenals of the US, with over 3,700, and Russia, with about 4,300. However, the growth has been significant: in 2012, when Xi Jinping came to power, the country had around 240 warheads. If the current trend continues, Pentagon estimates suggest that the Chinese arsenal could reach or even exceed 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030.

Around Lop Nor, not only military secrets accumulate. Long before the place became associated with China's nuclear program, Western explorers of the 19th century already spoke of an unstable territory, where maps became unreliable because the ancient lake dried up completely for much of the year. The Swedish explorer Sven Hedin described it as a "wandering lake".

This atmosphere of uncertainty became darker in the 20th century. One of the most cited episodes in China is the disappearance in 1980 of scientist Peng Jiamu, who was part of a scientific expedition in the region. Peng wandered away from the camp to look for water and never returned. The case fueled all kinds of rumors - from accidents in nearby military facilities to alien theories - and even today his name appears in reports and documentaries as a symbol of the enigmas of Lop Nor.